2 Code and Data

Feel free to skip this chapter if you already know some R or have some familiarity with sports data. This chapter is mostly included for completeness and I considered not including it. It is important not because it is necessarily informative, but because it gives us the raw material from which we will divine our insights.

Data is the fuel for analytics work, and your business strategy should be derived from some objective justifications. Every piece of code in this book is available, should run on your machine, and can be hacked and adapted to similar problems. We will be using R and R Studio 22 as our primary analysis tool. R is a great choice for analyzing sports data. While I find R a bit idiosyncratic, you don’t have to dream in C++ to use it. If you like to script a little bit, but don’t want to be a full-on developer, R is your ticket. Additionally, R Studio is a great IDE for analysis. It has a ton of useful features that will make your life much easier.

If you don’t have very much coding experience, this chapter gives me an opportunity to familiarize you with some code and with the data that you will encounter. We’ll cover the basics of exploring and analyzing a data set in the next chapter.

In this chapter we’ll cover several subjects:

- The main building blocks of scripting for analysis

- Understanding common data sets in the context of professional sports

- Constructing some sample data sets to mimic these data sets

- Building an R package to reference these data sets throughout the rest of the book

The particulars of ticketing datasets vary and a small number of companies dominate the sports industry. TicketMaster is common in pro sports. Paciolin is another player in this arena, but they are more common in college sports and other venues. Ultimately, the system won’t matter. You’ll have to transform the data into a format that will be useful for an analytics process.

For our purposes, we’ll invent a professional baseball team, the Nashville Game Hens. The Game Hens were an expansion team in 2017 and play a typical baseball schedule of 162 games.

2.1 Some basic notes on the R language

This chapter will introduce you to some R code. Ultimately, it doesn’t matter what tool you use. Python, Julia, R, Stata, SAS, and Matlab all provide some similar functionality. However, being confronted with code can be a little overwhelming at first. We are leveraging code (particularly R) for a few reasons.

- If your analysis is done in code each step is readily reproducible and documented

- R is free, easy to use, has a large user base, and has a great IDE

- R is massively extensible for smaller-scaled tasks

- It is a great tool for protyping something you might put into production in a more perfomant environment

I have found that it is best to get good at one tool and to stick with it. However, I say this with a note of caution. Let’s consider a quote from a famous poem.

“Things fall apart; the center cannot hold”

Willaim Butler Yeats, “The Second Coming”

Technologies are doomed to obsolescence. While many legacy technologies have endured for decades (Fortran, Cobal, R, Python, C, C++), they have all evolved. Technologies are doomed to be eclipsed by better tools. For instance, R isn’t the best tool to build large-scale web applications. Don’t be so rigid that you devote your personal brand to a particular technology. You might find yourself on the scrap-pile with it… “Things fall apart.”

R is relatively simplistic on the outside relative to many other languages. It has a more limited number of data structures, doesn’t use scalars, is single-threaded, and tends to avoid standard flow-control. It is a little peculiar. If you have some programming experience with another language you might find yourself having a little difficulty with it. If you are new to programming, it is going to look weird. R has been extended by thousands of developers and we are simply writing scripts that piggyback off of other programmer’s’ work. Many of them have done a fabulous job of creating a free tool that currently rivals any others in the analytics space 23.

Additionally, I recommend using code instead of a point-and-click tool. Code demonstrates exactly what you have done and is easy to communicate to anyone with a knowledge of the language. It will make your life easier even if it makes it more difficult in the beginning. The best thing about R is that there has been a huge user base over the years and there are many resources that you can leverage to learn what it can do. Ultimately, the decision on what tool to use needs to be driven by what you want to get out it. Are you prototyping or do you need to operationalize your code? Are you dealing with huge datasets? Do you want something built for speed or comfort? I am not going to cover very much about the language in this book. There are just too many resources available that will do a better job than me. Here are my basic recommendations if you would like to use R:

- Get an IDE that you like. RStudio is currently the best choice for R by a wide margin.

- Download R (R Core Team 2022).24 It works on all major platforms and find some free classes on how to use it. There are hundreds of how-tos available online. You can also purchase many books that will teach you how the language works. My favorite is “Advanced R” (Wickham 2014) and I highly recommend it as a must-have reference book.

- Practice it! It doesn’t take long to get over-the-hump in terms of getting some functional fluency. I consider it similar to playing an instrument. “Flight of the bumblebee” 25 doesn’t need to be the first song that you learn on piano. Start simple and build on your knowledge. You will eventually develop an intuitive understanding of what your tool can do.

It is also important to consider that R does have some drawbacks.

- A language won’t tell you what you should do. It only provides methods to execute functions. You still need to understand how to approach and solve your problem. R won’t help you here unlike specialized statistical tools such as Minitab26.

- R can be relatively slow if you don’t use it correctly. This has to do with how it was constructed 27. However, there are ways to speed it up significantly. Rcpp (Eddelbuettel et al. 2022) is an almost seamless api to C++ that will allow you to build and leverage C++ functions in your R environment. It is a highly leveraged and important tool in R world.

- R may not be the best choice for putting something into operation. Many people prototype with R and then leverage another tool to put the work to use. However, there are some great tools for smaller scale web deployments built on the Shiny framework.

- It’s user base may decline in favor of other tools. Python has become more popular in recent years. Languages tend to benefit from network effects where the more users that it has, the more features that are built for it. User-base size is very important.

Some of the following sections will demonstrate how the datasets for this book were created. I think that this is important to do for a couple of different reasons.

- You may not be familiar with R. The code sections will get you familiar with how it looks and works.

- If you don’t work with data in sports, the data is going to be foreign to you. This is an opportunity to explain the data sets.

One other comment I want to make is on coding in-general. It is easier to write code than to read somebody else’s code. To that end, I like comments. While in many cases the code can act as the documentation, I like to add explicit descriptors. I don’t make them detailed. I just give you enough to know what the code block is doing. I’ll follow this practice throughout the book.

These data sets and the code used to create them are available in the R package FOSBAAS and are publicly available, so there is no reason to type any of the following sections, but suit yourself. You can download a file with all of the code in this book here: https://github.com/Justin-Watkins/FOSBAAS/blob/master/FOSBAAS_code.R.

Additionally, this book will make use of many libraries. You can run the following code to make sure that most of them are installed:

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Install libraries

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

libraries <-

c('AlgDesign','anacor','car','caret','data.table','devtools','dplyr','forcats',

'ggplot2','GPArotation','Hmisc','knitr','lubridate','maps','mgcv','mice',

'mlr','mlr3','nFactors','nnet','plyr','poLCA','pricesensitivitymeter','pROC',

'pscl','psych','purrr','pwr','ranger','RColorBrewer','renv','reprex','Rcpp',

'reshape2','reticulate','roxygen2','rpart','rpart.plot','rsample','scales',

'shiny','stargazer','stats','tibble','tidymodels','tidyr','tidyverse',

'viridis','xtable')

install.packages(setdiff(libraries,

rownames(installed.packages()))) Keep in mind that certain functions will deprecate over time. Additionally, you can end up with problems if certain functions have the same names as functions in other packages. R is so dependent on packages that you’ll want to look into a way to keep your environments stable. The renv (Ushey 2022) package will handle some of this work for you. As you begin writing more complex code you’ll want to use one of these dockering programs. There is an older package called Packrat that does the same thing. I also included the reprex (Bryan et al. 2022) package in this list. reprex produces reproducible examples and you’ll want to use it if you are asking for help on a piece of code. It is really useful, so check it out.

2.2 Simulating customer renewal data

The code in this book typically does three things over and over again:

- Write functions

- Apply those functions to data

- Graph the output

The first data set that we will create will be related to building a model to estimate the likelihood that a season ticket holder will renew season tickets. This data is difficult to create because we need to build certain patterns into the data that build on each other. The goal of this section is to build a function that will produce a data set on command. Due to the fact that it builds on itself, it is difficult to generalize the function. To that end it doesn’t demonstrate good programming practice, but it does have many elements that you will need to progress further.

When we build a function, we will denote it with a prefix f-underscore and each word will be separated with an underscore. Columns in data sets will follow camel case (camelCase) where the first letter of each word is capitalized and there are no spaces between the words. You don’t have to do it like this, but I have found that it works for me. Whatever you do, choose one way of doing this. You’ll be glad that you did.

We will begin by creating the function FOSBAAS::f_create_lead_scoring_data. A best practice is to name a function in a way that tells you exactly what it does. If you aren’t familiar with building functions, they are easy to understand. We already looked at an example. A simple function that outputs a y in terms of x is a linear function where m = slope and b = the y intercept:

\[\begin{equation} \ {y} = {m}{x} + {b} \end{equation}\]

You can think of the functions that we will write to build our data sets in the same way. We will input a variable (or multiple variables) and the function will process the variables and output a value. An R function to output a y value for x based on a linear equation would look like this.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Linear equation function

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

f_linear_equation <- function(x,slope,yIntercept){

y <- slope*x + yIntercept

return(y)

}You will input values for x, the slope, and the y-intercept, and the function will return a value for y. This is a very simplistic example, but it demonstrates functions very well. Let’s try it.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Linear equation function inputs

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

f_linear_equation( x = 2,

slope = 10,

yIntercept = 7)

#> [1] 27Now we have a simple function that we can use to get the y value where x = 2, the slope of the line is 10, and the y intercept is 7. Input, process, output. You now that you have an understanding of the way a function works, you need a way to repetitively apply that function to data. You can do that in many different ways. In most programming languages you’ll use a For loop. We wrapped each following snippet in the system.time() function to demonstrate differences in the speed of each operation.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# fake data

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

x <- seq(from=1,to=1000000,by=1) # x values

m <- 10 # Slope

b <- 7 # Y Intercept

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# 1. For Loop

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

line_value <- list()

system.time(

for(i in x){

line_value[i] <- x[i]*m + b

}

)

#> user system elapsed

#> 1.08 0.03 1.11

line_value[1:3]

#> [[1]]

#> [1] 17

#>

#> [[2]]

#> [1] 27

#>

#> [[3]]

#> [1] 37A while loop does the same thing, but is open-ended and is generally used much less frequently. In python, while loops are typically discouraged. However, I find them easier to read than other methods found here. What you choose to use should consider how fast it might run and readability. Just work with what you find most comfortable if you aren’t working with large data sets.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# 2. While Loop

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

i <- 1 # Iterator

line_value <- list()

system.time(

while(i <= length(x)){

line_value[i] <- x[i]*m + b

i <- i + 1

}

)

#> user system elapsed

#> 0.94 0.03 0.97

line_value[1:3]

#> [[1]]

#> [1] 17

#>

#> [[2]]

#> [1] 27

#>

#> [[3]]

#> [1] 37A third approach, and the one that is preferred is to use an apply function. See ?apply. These functions might be more confusing at first, but they are useful and typically work much more quickly.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# 3. lapply

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

system.time(

line_value <- lapply(1:length(x), function(i) x[i]*m + b)

)

#> user system elapsed

#> 0.86 0.03 0.89

line_value[1:3]

#> [[1]]

#> [1] 17

#>

#> [[2]]

#> [1] 27

#>

#> [[3]]

#> [1] 37The apply functions have even been improved upon in specific ways. The following snippet uses the imap function from the purrr (Henry and Wickham 2020) package.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# 4. purrr:imap

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

system.time(

line_value <- purrr::imap(x,~ .x*m + b)

)

#> user system elapsed

#> 1 0 1

line_value[1:3]

#> [[1]]

#> [1] 17

#>

#> [[2]]

#> [1] 27

#>

#> [[3]]

#> [1] 37These are the basic tools that you will use for everything we are going to do going forward. As I said, there are tradeoffs that you will need to contemplate. Speed and readability are important considerations. Ultimately, you can use whatever you feel most comfortable with.

The following sections will demonstrate the functions used to build some of the data sets that you will find in this book. We won’t go into full detail with every data set. Full documentation on them can be found in the help section of the FOSBAAS package. Additionally, we did something a little strange on this first function, we feed it other helper functions. One of the helper functions requires the use of a function as well. We won’t do this on the other data sets, but it is an important feature of R to understand. Everything you do in R can be based on a function, and you can use them in a similar way to methods in other languages.

We have already built these functions. The first one simply creates data for lead scoring. Lead scoring means that we are going to use the data to predict which groups of people are more likely to purchase a ticket.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Create lead scoring data

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

library(FOSBAAS)

f_create_lead_scoring_data(714,

5000,

"2021",

f_calculate_tenure,

f_calculate_spend,

f_calculate_ticket_use,

f_renewal_assignment,

f_assign_renewal,

renew = T)This function also accepts several arguments:

- A

seedvariable that enables us to create reproducible data sets. - the number of rows that we want.

- Five functions that create tenure, spend, and ticket usage

- Two functions that help assign renewal

- A renewal argument that will produce a column indicating if the account renewed.

If you want to see the code that this function uses, you can use the following command (Assuming you installed the package):

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# View your functions

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

edit(getAnywhere('f_create_lead_scoring_data'),

file = 'f_create_lead_scoring_data.r')Calling this function will produce a data set that looks something like this. If you use the same parameters, you will get exactly the same data.

| variable | class | first_values |

|---|---|---|

| accountID | character | WD6TDY7C151R, X3SB8ADEML22 |

| corporate | character | i, c |

| season | double | 2021, 2021 |

| planType | character | p, f |

| ticketUsage | double | 0.728026975947432, 0.992104738159105 |

| tenure | double | 2, 19 |

| spend | double | 4908, 16410 |

| tickets | double | 6, 2 |

| distance | double | 61.6614648674555, 19.5341155295423 |

| renewed | character | nr, nr |

This data set includes several columns:

- An account id representing a specific individual

- Is the account used by a company or an individual

- The season year

- The plan type (Partial season or Full season)

- Ticket usage percentage

- The number of years the account has been with us

- The amount spent on tickets in 2021

- Distance from the ballpark

- Did the account renew at the end of the season

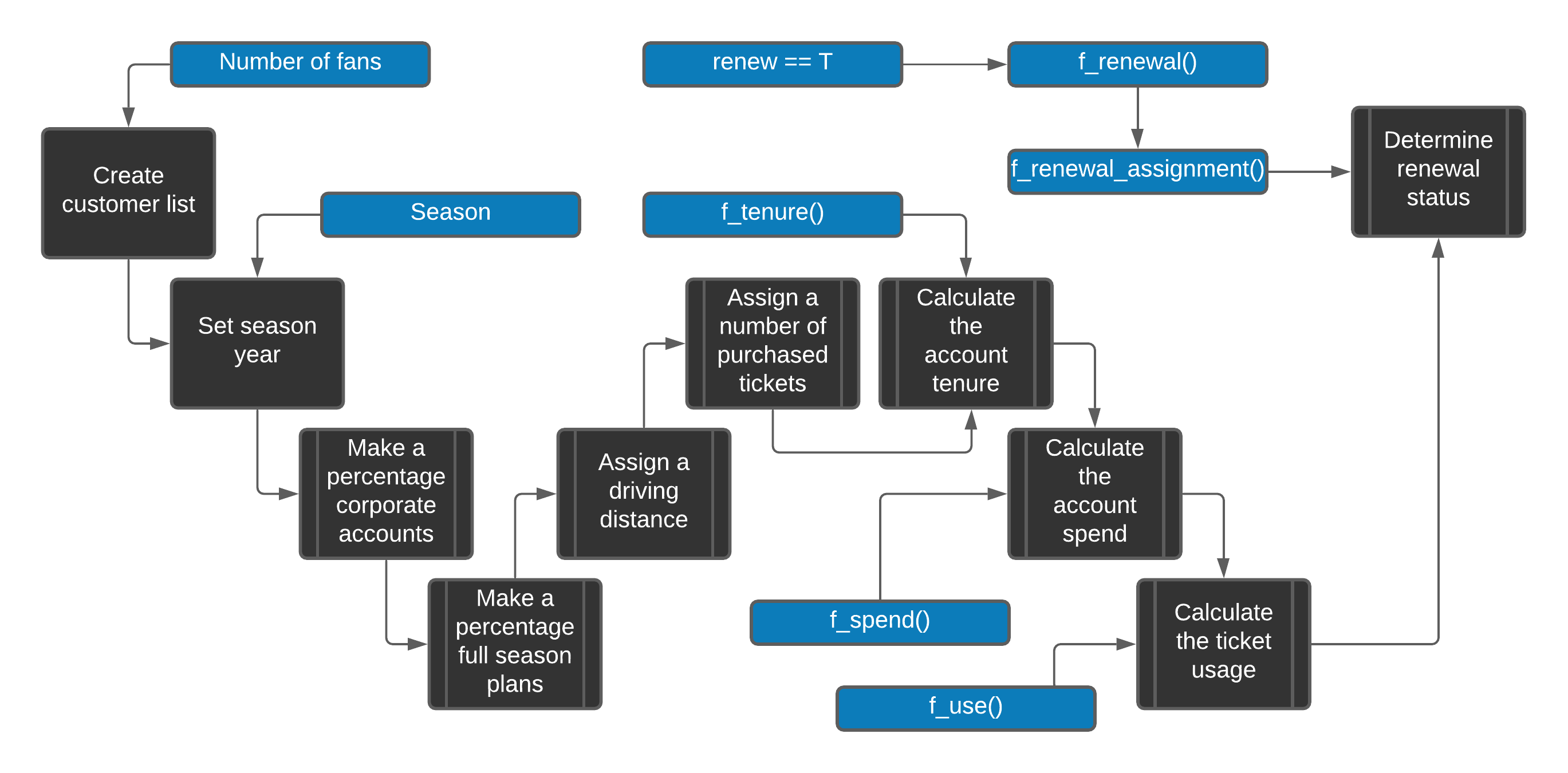

This process is a little involved (see figure 2.1). Let’s walk through it step by step.

Figure 2.1: Data creation process

2.2.1 Building our function

The following code creates a dataframe with nine columns and then assigns a list of names to each column. Think of a dataframe as an excel workbook. R uses <- for assignment, however you can use the = sign if you prefer. We then use the sapply function to create a sequence of random letters and numbers to represent account ids. The apply functions are incredibly important. You can type ?sapply into the console in R studio if you want to learn more.

This looks weird. sth_data[,1] references the first column in the data frame dataframe[row,column]. The first argument in sapply is giving the function a list of rows to traverse. The second argument uses something called an anonymous function, which is confusing. Look it up if you want a deeper understanding of it. It will begin to make sense as you play with it. paste(sample(c(0:9, LETTERS), 12, replace=TRUE),collapse = "")) simply creates a random twelve digit alphanumeric string. We follow this up with assigning a season to the season column.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# 1. Create a data frame to hold our data

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

sth_data <- data.frame(matrix(nrow=num_purchasers,ncol=9))

names(sth_data) <- c("accountID","corporate","season",

"planType","ticketUsage","tenure",

# 2. Build ids and append to customer data frame

set.seed(seed)

sth_data[,1] <- sapply(seq(nrow(sth_data)), function(x)

paste(sample(c(0:9, LETTERS), 12, replace=TRUE),

collapse = ""))

# 3. Assign a season year to the data

sth_data$season <- seasonMany season ticket accounts are owned by corporations. We’ll build a list called corporate and sample it in order to assign a “c” for corporate or “i” for individual to each account. We use the set.seed() function for reproducibility. We’ll use the sample function to sample a c or an i from the list at the rate of 20% corporations and 80% individuals using the prob argument.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# 4. Assign corporate or individual to each account

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

set.seed(seed)

corporate <- c("c", "i")

sth_data$corporate <-

sapply(seq(nrow(sth_data)),

function(x) sample(corporate,

1,

replace = TRUE,

prob = c(.20, .80)))Season ticket holders can purchase full or partial plans. The proportions change based on if they are a corporate or individual account. These statements could have been generalized and turned into a function. However, we only had to copy-and-paste once, so we left it alone. Always look for opportunities to generalize functions. This function operates exactly the same way as the previous one.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# 5. Assign a plan type to each account

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Corporations

set.seed(seed)

planType <- c("f","p")

sth_data[which(sth_data$corporate == "c"),]$planType <-

sapply(seq(nrow(sth_data[which(sth_data$corporate == "c"),])),

function(x) sample(planType,

1,

replace = TRUE,

prob = c(.95, .5)))

# Individuals

planType <- c("f","p")

sth_data[which(sth_data$corporate == "i"),]$planType <-

sapply(seq(nrow(sth_data[which(sth_data$corporate == "i"),])),

function(x) sample(planType,

1,

replace = TRUE,

prob = c(.60, .40)))To simulate a distance from the stadium we’ll leverage the rexp() function to give us an exponentially distributed list of numbers that we can modify and sample for each account. This density pattern is common in many urban areas where population density is much higher in certain centralized areas. We’ll show you how to visualize this pattern in a subsequent chapter. The outcome here is that individuals will tend to live further away than corporations.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# 6. Calculate the distance from the stadium

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

set.seed(seed)

distances_corp <- rexp(num_purchasers) * 12

distances_indv <- rexp(num_purchasers) * 30

# Corporate

set.seed(seed)

sth_data[which(sth_data$corporate == "c"),]$distance <-

sapply(seq(nrow(sth_data[which(sth_data$corporate == "c"),])),

function(x) sample(distances_corp,

1,

replace = TRUE))

# Individuals

sth_data[which(sth_data$corporate == "i"),]$distance <-

sapply(seq(nrow(sth_data[which(sth_data$corporate == "i"),])),

function(x) sample(distances_indv,

1,

replace = TRUE))Next, we’ll build a list of numbers that will refer to the number of season tickets purchased by each account. We’ll then assign a number of tickets based on the distributions denoted in the prob argument of the sample() function. Basically, we want corporations to purchase more tickets.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# 7. Determine the number of tickets each account has purchased

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

tickets <- c(10,8,6,5,4,3,2,1)

set.seed(seed)

# Corporations

sth_data[which(sth_data$corporate == "c"),]$tickets <-

sapply(seq(nrow(sth_data[which(sth_data$corporate == "c"),])),

function(x) sample(tickets, 1, replace = TRUE,

prob = c(.02,.08,.10,.05,.50,.05,.20,0)))

# Individuals

sth_data[which(sth_data$corporate == "i"),]$tickets <-

sapply(seq(nrow(sth_data[which(sth_data$corporate == "i"),])),

function(x) sample(tickets, 1, replace = TRUE,

prob = c(0,0,.10,.05,.40,.05,.30,.10))) For tenure, if we set the renew argument = TRUE, we leverage our f_tenure function to assign the number of years based on a list of arguments that we have created within our main function. Flow control with conditions is really important to understand. A simple way to explain them is like this: “If(some condition == TRUE), then do something. If(condition == FALSE), then do something else”. In R, == is used to compare things. = is used for assignment.

In this function we use mapply. It works like sapply, but it accepts multiple arguments. We also used a with statement. With just means you have to type less. It tells R that everything within it belongs to one frame of data.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# 8a. Assign years the account holder has had tickets

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

if(renew == T){

avgDist <- mean(sth_data$distance)

set.seed(seed)

tenures <- with(sth_data,mapply(f_calculate_tenure,

corporate,

planType,

distance,

avgDist))

sth_data$tenure <- as.vector(tenures)

}else{sth_data$tenure = 0}The f_calculate_tenure() function accepts four arguments. These arguments are constructed from the code chunks that we have been running. This function is simply a long if-else statement. We did it like this because we have specific patterns we would like to construct within the tenure column.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# 9b. Function to calculate tenure

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

f_calculate_tenure<-function(corporate,planType,distance,avgDist){

if(corporate == "c" & planType == "f" & distance <= avgDist){

ten <-round(abs(rnorm(1,mean = 14,sd = 6)),0)}

else if(corporate == "i" & planType == "f" & distance <= avgDist){

ten <-round(abs(rnorm(1,mean = 10,sd = 6)),0)}

else if(corporate == "c" & planType == "p" & distance <= avgDist){

ten <-round(abs(rnorm(1,mean = 3,sd = 2)),0)}

else if(corporate == "i" & planType == "p" & distance <= avgDist){

ten <-round(abs(rnorm(1,mean = 3,sd = 2)),0)}

else if(corporate == "c" & planType == "f" & distance >= avgDist){

ten <-round(abs(rnorm(1,mean = 9,sd = 3)),0)}

else if(corporate == "i" & planType == "f" & distance >= avgDist){

ten <-round(abs(rnorm(1,mean = 7,sd = 3)),0)}

else if(corporate == "c" & planType == "p" & distance >= avgDist){

ten <-round(abs(rnorm(1,mean = 2,sd = 1)),0)}

else if(corporate == "i" & planType == "p" & distance >= avgDist){

ten <-round(abs(rnorm(1,mean = 2,sd = 1)),0)}

else{ten <-round(abs(rnorm(1,mean = 8,sd = 3)),0)}

return(ten)

}We based season ticket holder spend on tenure, plan-type, and the account type.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# 9a. SPEND

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

avgTenure <- mean(sth_data$tenure)

set.seed(seed)

spend <- with(sth_data,mapply(f_calculate_spend,

corporate,

planType,

tenure,

avgTenure))

sth_data$spend <- as.vector(spend) * sth_data$ticketsThe function f_calculate_spend uses the rnorm() function. This function accepts a mean and standard deviation argument that allows us to sample a number on a specific normal distribution. Once again, we could have generalized this function a little more, but since it’s just a helper function with one purpose we hard-coded our numbers into it.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# 9b. Function to calculate spend

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

f_calculate_spend<- function(corporate,planType,tenure,avgTenure){

if(corporate == "c" & planType == "f" & tenure >= avgTenure){

spend <-round(abs(rnorm(1,mean = 7500,sd = 800)),0)}

else if(corporate == "i" & planType == "f" & tenure >= avgTenure){

spend <-round(abs(rnorm(1,mean = 2100,sd = 500)),0)}

else if(corporate == "c" & planType == "p" & tenure >= avgTenure){

spend <-round(abs(rnorm(1,mean = 2000,sd = 300)),0)}

else if(corporate == "i" & planType == "p" & tenure >= avgTenure){

spend <-round(abs(rnorm(1,mean = 1200,sd = 200)),0)}

else if(corporate == "c" & planType == "f" & tenure <= avgTenure){

spend <-round(abs(rnorm(1,mean = 5000,sd = 500)),0)}

else if(corporate == "i" & planType == "f" & tenure <= avgTenure){

spend <-round(abs(rnorm(1,mean = 2000,sd = 300)),0)}

else if(corporate == "c" & planType == "p" & tenure <= avgTenure){

spend <-round(abs(rnorm(1,mean = 2000,sd = 400)),0)}

else if(corporate == "i" & planType == "p" & tenure <= avgTenure){

spend <-round(abs(rnorm(1,mean = 800,sd = 75)),0)}

else{spend <-round(abs(rnorm(1,mean = 2500,sd = 300)),0)}

return(spend)

}Ticket usage represents the percentage of tickets used:

\[\begin{equation} \ {ticketUsage} = {totalTicketsUsed} / {totalTickets} \end{equation}\]

Similarly to the previous examples, we are building ticket usage in a particular way.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# 10a. Calculate the percentage of tickets used

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

avgDist <- mean(sth_data$distance)

set.seed(seed)

ticket_use <- with(sth_data,mapply(f_calculate_ticket_use,

corporate,

distance,

avgDist))

sth_data$ticketUsage <- as.vector(ticket_use)The function f_calculate_ticket_use uses the runif() function that produces a random number on a uniform distribution based on a minimum and maximum value. These numbers are also hard-coded so that we can produce specific patterns.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# 10b. Function to return ticket usage

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

f_calculate_ticket_use <- function(corporate,distance,avgDist){

if(corporate == "c" & distance <= avgDist){

tu <- runif(1,min = .89, max = 1)}

else if(corporate == "i" & distance <= avgDist){

tu <- runif(1,min = .82, max = .94)}

else if(corporate == "c" & distance >= avgDist){

tu <- runif(1,min = .65, max = .9)}

else if(corporate == "i" & distance >= avgDist){

tu <- runif(1,min = .55, max = .85)}

else{tu <- runif(1,min = .65, max = .95)}

return(tu)

}Finally, we check the renew argument and if (using an if statement) it is true, we determine if the account renewed its tickets based on the values in the dataframe sth_data. If renew_ = _F, we return our dataframe without a renewed field.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# 11a.Return proper data frame

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

if(renew == T){

sth_data_renew <- f_renewal_assignment(seed,sth_data,

f_assign_renewal)

return(sth_data_renew)

}else{ return(sth_data)}The following statement uses two functions: f_assign_renewal() and f_renewal_assignment(), which is a little confusing. f_assign_renewal() is a helper function that assigns a renewal value based on a cluster assignment designated in f_renewal_assignment().

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# 11b.Calculate renewal percentage

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

f_assign_renewal <- function(x,renew){

if(x == 10){sample(renew,1,prob = c(.99,.01))}

else if(x == 9){sample(renew,1,prob = c(.98,.02))}

else if(x == 8){sample(renew,1,prob = c(.95,.05))}

else if(x == 7){sample(renew,1,prob = c(.95,.05))}

else if(x == 6){sample(renew,1,prob = c(.92,.08))}

else if(x == 5){sample(renew,1,prob = c(.90,.10))}

else if(x == 4){sample(renew,1,prob = c(.85,.15))}

else if(x == 3){sample(renew,1,prob = c(.80,.20))}

else if(x == 2){sample(renew,1,prob = c(.30,.70))}

else if(x == 1){sample(renew,1,prob = c(.25,.75))}

else{sample(renew,1,prob = c(.5,.5))}

}f_renewal_assignment() accepts f_assign_renewal() as an argument. It does a couple of things. First, it clusters ticket_usage and distance using the kmeans() function. We’ll cover some clustering exercises in chapter 4. The cluster assignments are added together and biased renewals are assigned based on how high or low the number is. Higher numbers are more likely to renew. We use a while loop instead of the mapply() function in this example. Vectorizing the loop with an apply() function is typically a better method when using R.

This function is more complex than the others and has a dependency dplyr. We also call a list() which is the most used data structure in R. A list is simply an indexed array. Dataframes are collections of lists.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# 11c.Calculate renewal percentage

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

f_renewal_assignment <- function(seed,sth_data,f_assign_renewal){

require(dplyr)

ids <- as.data.frame(sth_data$accountID)

names(ids) <- "accountID"

set.seed(seed)

centers1 <- kmeans(sth_data$ticketUsage, centers = 5)$centers

centers1 <- sort(centers1)

ids$clusterTU <-

kmeans(sth_data$ticketUsage, centers = centers1)$cluster

set.seed(seed)

centers2 <- kmeans(sth_data$distance, centers = 5)$centers

centers2 <- rev(sort(centers2))

ids$clusterDI <-

kmeans(sth_data$distance, centers = centers2)$cluster

ids$clustSum <- ids$clusterTU + ids$clusterDI

sth_data_renew <- dplyr::left_join(ids,sth_data,

by = "accountID")

x <- 1

renew <- c("r","nr")

a_renew <- list()

while(x <= nrow(sth_data_renew)){

clust <- sth_data_renew[x,3]

a_renew[x] <- f_assign_renewal(clust,renew)

x <- x + 1

}

sth_data_renew$renewed <- unlist(a_renew)

sth_data_renew <- dplyr::select(sth_data_renew,accountID,

corporate,season,planType,

ticketUsage,tenure,

spend,tickets,distance,

renewed)

return(sth_data_renew)

} # EndWe just walked through everything in figure 2.1. This process would be much more succinct if the patterns that we are constructing weren’t based on specific features that we are creating. However, we were able to take a look at several programming features and some features endemic to R.

- Building your own functions

- The apply family of functions

- If statements

- While/for loops

- kmeans clustering

- rnorm and rexp functions for distributions

- runif for creating random numbers

- subsetting with dplyr

We can now call the function with different input variables to produce a different result:

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Function to build a parabola

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

library(FOSBAAS)

new_data <- f_create_lead_scoring_data(434,

100,

"2023",

f_calculate_tenure,

f_calculate_spend,

f_calculate_ticket_use,

f_renewal_assignment,

f_assign_renewal,

renew = F)Calling this function will produce a data set that looks something like this:

| variable | class | first_values |

|---|---|---|

| accountID | character | IQ7G9BPWYJSD, L3TA5OEHCAAF |

| corporate | character | i, i |

| season | character | 2023, 2023 |

| planType | character | f, f |

| ticketUsage | double | 0.726619377103634, 0.880502448994666 |

| tenure | double | 0, 0 |

| spend | double | 8848, 4892 |

| tickets | double | 4, 2 |

| distance | double | 25.237493169165, 4.39980797935277 |

This is a typical data set that you would find in the wild. The data is also beautiful. By beautiful I mean that it isn’t missing features and will be easy to prep for analysis. This is not something that you typically find. We’ll discuss what to do with incomplete data and other problems further into the book.

We can now use this function to produce as many different data sets as we would like. We’ll follow this same procedure of building helper functions to build our other data sets.

2.3 Simulating Operations data

Operations data includes many different data sets. We’ll cover building a ballpark ingress scans table here. However, there could be many others such as line length at a concessions stand or the number of transactions for F&B.

2.3.1 Ticket scans

First we can build a simple function to help us build a parabola. This function builds a parabola that has an x intercept at x = 1 and x = 300. These points will refer to the number of observations that we will make in Chapter 10. All we are doing is building a quadratic function that spits out a y value for a value of x. This function takes the familiar form of a quadratic function:

\[\begin{equation} \ {f(x)} = {ax^2} + {bx} + c \end{equation}\]

#--------------------------------------------------------------------

# Function to build a parabola

#--------------------------------------------------------------------

f_calc_scans <- function(x,y,j){

a <- y/(x^2 - 300*x + 300)

z <- a*(j^2 - 301*j + 300)

return(z)

}We can then build a function to create many different data sets. This function will calculate the number of scans per increment on a normal distribution.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Function to return a scans data frame

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

f_get_scan_data <- function(x_value,y_value,seed,sd_mod){

require(FOSBAAS)

x_val <- x_value

y_val <- y_value

obs <- seq(1,300, by = 1)

set.seed(seed)

scans <- mapply(f_calc_scans,x_val,y_val,obs)

scan_data <- data.frame(observations = obs,

scans = scans)

scan_data$scans <- round(sapply(scan_data$scans,

function(x) abs(rnorm(1,x,x/sd_mod))),0)

return(scan_data)

}This function will produce a data set that looks like this:

scan_data <- FOSBAAS::scan_data| observations | scans | action_time | date |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 61200 secs | 4/1/2024 |

| 2 | 2 | 61260 secs | 4/1/2024 |

| 3 | 4 | 61320 secs | 4/1/2024 |

| 4 | 7 | 61380 secs | 4/1/2024 |

| 5 | 10 | 61440 secs | 4/1/2024 |

| 6 | 11 | 61500 secs | 4/1/2024 |

This tells you the number of scans that happened in one minute increments on a particular event.

2.4 Simulating and understanding ticketing data sets

Ticketing data seems like it should be relatively straight-forward. It isn’t. There is a lot of complexity. The environment is very dynamic, and in some cases we can get into big-data territory. For the context of this book, we stay away from big-data problems. Many big-data problems are nothing more than small-data problems in disguise. Because of the nature of sports, three years of data is likely enough to do everything that we will need.

We’ll begin by simulating three seasons worth of data. For the sake of simplicity, we’ll transform the data into a format that will be useful for the applications we’ll be demonstrating throughout the book. There are four features of this data that are the most important:

- Customer details and demographics

- Ticket purchases (including secondary market purchases)

- Plan purchases

- Qualitative data obtained through surveys

Elements of the season will be important from a macro level. Some of our analysis will cover a top-down approach to forecasting sales and revenue.

2.5 Simulating season data

Professional baseball teams typically play 81 games. We’ll be simulating three seasons of data. While building a schedule is a complex process, we aren’t hindered by the myriad constraints and will therefore make this easy on ourselves. The schedule will provide the framework for the customer and ticketing data that we will build in subsequent sections of this chapter. It is also important to note that this is a top-down approach as opposed to bottom-up approach consisting of sales at a more granular level.

2.5.1 Function to manually bias our season data

This function f_simulate_sales modifies certain characteristics we’ll use to forecast sales. It is creating distributions of numbers that will be used to place our variables on a defined range of possibilities. Instead of walking through the code this time, I’ll just tell you what it does:

- Creates a base attendance for each team. For instance, if we play BOS, CHC, NYY, LAD, or STL we get the highest sales base.

- If the day of the week falls on the weekend the sales base is higher than a weekday.

- If we are playing in the summer months, sales are higher.

- If school is out, sales are higher.

- If it is the last game of the year, sales are higher.

- If it is opening day, sales are higher.

- If there is a bobblehead, sales are higher

This function creates a pattern in the ticket sales data based on the averages of normal distributions. You can access the function through the FOSBAAS package.

This function accepts several arguments. One of them is the function f_simulate_sales. It asks for three random numbers, three modifiers which are simply coefficients to bias the results further, and a season.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Function to build season data

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

seed1 <- 309

seed2 <- 755

seed3 <- 512

modifier <- 1.00

dayMod <- 1.10

monthMod <- 1.15

seasonYear <- '2023'

season23 <- f_build_season(seed1,

seed2,

seed3,

seasonYear,

f_simulate_sales,

modifier,

dayMod,

monthMod)The resulting data set looks like this:

season_data <- FOSBAAS::season_data| variable | class | first_values |

|---|---|---|

| gameNumber | double | 1, 2 |

| team | character | SF, SF |

| date | double | 2022-03-27, 2022-03-28 |

| dayOfWeek | character | Sun, Mon |

| month | character | Mar, Mar |

| weekEnd | logical | FALSE, FALSE |

| schoolInOut | logical | FALSE, FALSE |

| daysSinceLastGame | double | 50, 1 |

| openingDay | logical | TRUE, FALSE |

| promotion | character | none, none |

| ticketSales | double | 42928, 25759 |

| season | double | 2022, 2022 |

This data set is a simulated schedule with several fields:

- The game number

- opposing team

- date

- day of the week

- the month

- if it was a weekend

- if schools is in or out

- the days since the last game

- if it is opening day

- if there was a promotion

- the number of ticket sales

- the season year

This is fine for a base package. When modeling you can obviously go much deeper and include statistics such as Las Vegas odds for the playoffs, more granular promotional data, and many others. We are ignoring the current divisional structure here for the sake of simplicity. Structuring a calendar is a complex task that involves many factors that we aren’t considering such as:

- Travel time

- Restrictions based on the collective bargaining agreement

- Team level requests

This data looks similar to data that you would actually have at the beginning of the season. We’ll use it to forecast ticket sales in chapter six. Another important piece of data is the manifest. The manifest represents seating inventory. It is interesting because it represents an upper bound for what is available to sell. A typical manifest would look like this:

manifest_data <- FOSBAAS::manifest_data| variable | classe | first_values |

|---|---|---|

| seatID | double | 1, 2 |

| section | double | 1, 1 |

| sectionNumber | double | 1, 1 |

| rowNumber | double | 1, 1 |

| seatNumber | double | 1, 2 |

| seasonPrice | double | 190, 190 |

| groupPrice | double | 199.5, 199.5 |

| singlePrice | double | 218.5, 218.5 |

2.5.2 Simulating customer data

This data set is simply a customer id and a name. We’ll make up some names for each id. We built our list of names from a couple of government websites (ssa 2020) and (Census 2020).

customer_data <- FOSBAAS::customer_dataWe’ll use this data frame to simulate a transformed data set that could be pulled from a ticketing system. Now we can use this data to create a data set for purchases on the secondary market.

secondary_data <- head(FOSBAAS::secondary_data)| variable | classe | first_values |

|---|---|---|

| seatID | double | 9010, 20950 |

| custID | character | N22J8UPWACNO, II3IGIN0PY15 |

| ticketType | character | se, se |

| gameID | double | 130, 111 |

| tickets | double | 1, 1 |

| priceKey | character | 9010_se, 20950_se |

| price | double | 54, 30 |

| orderedCluster | double | 8, 7 |

| secondayrPrice | double | 60.51, 37.11 |

This data set contains:

- A seat id corresponding to the manifest

- A customer id corresponding to our customer list

- The ticket type (single game si, season se)

- The game id from the schedule

- The number of tickets sold

- A key field

- The original price of the ticket

- A modeled cluster field

- The price sold on the secondary market

A completely clean data set like this is unlikely to be encountered outside of the lab. In reality, customer data will be fraught with duplication and other problems. This data is already transformed. In practice you would have to join a few tables to produce a data set that looks like this.

2.6 Simulating demographic data

Demographic data can be used for a variety of tasks such as segmentation and other targeted marketing efforts.

demo_data <- head(FOSBAAS::demographic_data)Demographic data is typically purchased from one of several vendors and may contain hundreds of columns. This data contains:

- A customer ID

- The first name of the customer

- The last name of the customer

- The full name of the customer

- Gender

- Age

- Latitude

- Longitude

- Distance from the ballpark

- marital status

- ethnicity

- children living in the household

- The county where the customer lives

2.7 Simulating survey data

We’ll use an example of survey data to construct a specific segmentation scheme based on a factor analysis. We’ll base some of this analysis on an example from Chapman and Feit’s excellent “R for Marketing Research and Analytics” (Chris Chapman 2015). We’ll cover survey construction in a later chapter.

2.7.1 Perceptual data

This initial data set will take the form of a multi-select table:

| Team | Friendly | Exciting | Winners | Losers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Came Hens | ||||

| Predators | ||||

| Grizzlies |

This data takes the form of an aggregated survey response where specific answers are counted and aggregated for each team in the questions. The question would read like this:

How do you feel about the following sports properties? Please check all that apply for each of the teams listed.

This question will allow us to create a perceptual map. We’ll send it to 5,000 of our customers that we created in Section 2.5.2.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

perceptual_data <- as.data.frame(matrix(nrow=3,ncol=10))

names(perceptual_data) <- c('Friendly','Exciting','Fresh',

'Inovative','Fun','Old','Historic',

'Winners','Great','Expensive')

row.names(perceptual_data) <- c('Game Hens','Grizzlies',

'Predators')

set.seed(2632)

perceptual_data <- apply(perceptual_data,1:2,

function(x) round(rnorm(1,3000,1000),0))This produces the following table:

| Friendly | Exciting | Fresh | Inovative | Fun |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1930 | 3080 | 1955 | 2128 | 2861 |

| 2646 | 4732 | 1444 | 2569 | 3508 |

| 2928 | 3783 | 2959 | 3831 | 3417 |

2.7.2 Pricing survey data

This data will be used to perform a Van Westendorp analysis and to demonstrate the basics of qualitative pricing analytics. You’ll want this data in a specific format.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

vw_data <- data.frame(matrix(nrow = 1000, ncol = 6))

names(vw_data) <- c('DugoutSeats', 'PriceExpectation',

'TooExpensive', 'TooCheap',

'WayTooCheap', 'WayTooExpensive')

set.seed(715)

vw_data[,1] <- 'DugoutSeats'

vw_data[,2] <- round(rnorm(1000,100,10),0)

vw_data[,3] <- round(rnorm(1000,130,20),0)

vw_data[,4] <- round(rnorm(1000,60,15),0)

vw_data[,5] <- round(rnorm(1000,50,10),0)

vw_data[,6] <- round(rnorm(1000,160,20),0)A Van Westendorp28 analysis asks the respondent to answer a series of questions about a product related to their perception of the price. The questions would take the following form:

- At what price would you consider the product to be so expensive that you would not consider buying it? (Too expensive)

- At what price would you consider the product to be priced so low that you would feel the quality couldn’t be very good? (Too cheap)

- At what price would you consider the product starting to get expensive, so that it is not out of the question, but you would have to give some thought to buying it? (Expensive/High Side)

- At what price would you consider the product to be a bargain—a great buy for the money? (Cheap/Good Value)

These questions were taken directly from the Wikipedia article. The resulting data set would resemble the following:

| DugoutSeats | PriceExpectation | TooExpensive | TooCheap | WayTooCheap | WayTooExpensive |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DugoutSeats | 100 | 115 | 57 | 39 | 170 |

| DugoutSeats | 113 | 147 | 69 | 52 | 129 |

| DugoutSeats | 102 | 169 | 67 | 51 | 163 |

| DugoutSeats | 103 | 134 | 72 | 54 | 148 |

| DugoutSeats | 99 | 88 | 46 | 37 | 163 |

| DugoutSeats | 83 | 123 | 77 | 59 | 145 |

These data sets represent the main top-line data that you would tend to use working for a club.

2.8 Housing your data and functions in a package

While this book isn’t meant to be an expose on how to use the R language, R has some great features for analytics work that are worth exploring. They will make our lives easier as we move through the subsequent chapters. Analytically focused work tends to be repetitive and housing your functions in a package will make your life easier and worth living. There are many resources available that make building your own package easy and we’ll cover the basics here.

There are two packages that will make building packages really simple: devtools (Wickham, Hester, et al. 2022) and roxygen (Wickham, Danenberg, et al. 2022). There are also numerous resources on how to build your own package. Rstudio even has some built-in-tools that makes this process even easier. I want to demonstrate this process because it is really easy and is incredibly useful.

2.8.1 Building a simple package

You’ll want to open RStudio and create a new R file. Creating a basic package only takes a few steps:

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Step 1: Download the utility packages

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

install.packages("devtools")

install.packages("roxygen2")

##browseVignettes("devtools")

##browseVignettes("roxygen2")Now that you have installed the packages that you need you can use them to create the package:

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Step 2: Create a shell for your package

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

devtools::create("UselessRPackage")You can then create a data set that we want to include in the package.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Step 3: Build a data set

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

devtools::document()

uselessData <- seq(1:755)We then place the data in the package.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Step 4: Place data set in package

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

usethis::use_data(uselessData, overwrite = T)Finally, we install the package.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Step 5: Install the package

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

devtools::install()You can access the data using your packages namespace.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Step 5: Access your data

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

UselessRPackage::uselessDataThere is a lot more that you have to do, especially around documentation. However, you have now housed data in a package that you can easily access. Once you begin using R more heavily I highly recommend putting some time into understanding how to create and use your own packages. This little feature will save you a lot of time. This also allows you to share your work through a service such a Github if you are working remotely or with a team.

2.9 Key concepts and chapter summary

This chapter was written to introduce you to a little code in R and to explain our data and data sets. It also demonstrates some of the concepts that we will cover in ensuing chapters. We also covered why R may or may not be a good choice for you to use for analysis.

Additionally, we covered the basics of how to build a package in R. Analysis tends to be repetitive. Housing some of your specific functions in a package is a very simple way to document what those functions do and to easily access them. R’s extensibility is one of its best features and makes it an incredibly flexible tool (especially when coupled with RStudio).

In Chapter 3 will delve into what to do with this data by creating graphics and summarizing some data. Subsequent chapters will explore additional functionality and will delve into solving more specific problems. They will also spend a significant amount of time explaining how to think about those problems and how to solve them.