6 Pricing and Forecasting

Like segmentation, writing an entire book on forecasting and pricing tickets would be easy due to the breadth of the subjects. There are innumerable considerations, such as determining a willingness to pay, taking arbitrage into account, cannibalizing your sales, margins, marketing channel, product suite, brand considerations, and competing internal goals. This chapter also immediately follows some examples of segmenting a market. This order is deliberate. Pricing is dynamic; in certain circumstances, products may be worth more or less money. However, pricing is only sometimes a deliberate exercise. Consider this quote found in Robert Phillips’ book “Revenue and Pricing Optimization” (Phillips 2005)

“In many cases, the prices charged to customers are the result of a large number of uncoordinate and arbitrary decisions.”

— Robert L. Phillips

I agree with Mr. Phillips’ sentiment. While pricing is a fundamental component of your marketing mix, it isn’t always well understood how it interacts with promotions and other marketing efforts (we’ll explore this a little in chapter 9). Additionally, we always have brand considerations to consider. Marketers often regress to the blunt instrument of lower prices to move more tickets. This tactic can be counterproductive in the long term. When a team isn’t good, lower prices will have less impact than when a team is performing well. However, there is less impetus to lower prices when a team performs well.

Pricing impacts your brand. Since season ticket holders are critical to risk mitigation, anything eroding their value should be scrutinized. This chapter will take you through a simplified example of how you can set prices and discuss the rationale behind our thinking. Then, we will use some real examples to demonstrate how this could be done in practice. However, we are only going knee-deep in the ocean. Pricing can be a challenging and complicated exercise.

6.1 Understanding your inventory

How do you value tickets? Let’s think about how your inventory might look. There are multiple ticket classes, and individuals may cross numerous classes. Additionally, certain conditions make your sales inventory fluid. For instance, if your goal is to maximize revenue, selling as many season tickets as possible may reduce revenue potential because they are sold at a discount. There is a tipping point. Other pieces of inventory may be inefficient to use during certain games. For instance, you may want to use something other than group discounts on an opening day where high demand obviates the need to sell discounted ticket classes. Typical ticketing inventory includes:

- Season tickets

- Group tickets

- Small plans

- Single-game tickets

- subscription tickets

Additionally, tickets may be obtained through several channels. Understanding channels is critical for pricing. Think of airlines. They exert significant control over their channels, enabling incredibly fine-grain control of pricing tactics. Typical ticketing channels include:

- Primary channels

- Directly through a team or league

- Through some consignment mechanism

- Through a ticketing system such as Ticketmaster

- Secondary channels

- SeatGeek

- StubHub

Secondary channels are even more nuanced because professional ticket brokers may own many tickets. These tickets may or may not exist in a liquid market that allows prices to float to any level. Ticket brokers represent a unique problem. Let’s discuss what ticket brokers are and do.

Ticket brokers buy and sell tickets to events. In a sports environment, there are two primary strategies. However, you can hedge your bets by purchasing multiple events and teams in the same or different sports. Other arbitrage opportunities might also exist, such as parking passes. The two main strategies are:

- Scale through the purchase of cheap inventory

- Purchase good inventory and maintain strong margins

Option number one can be risky. However, this varies by market. You purchase lots of inexpensive inventory and make money on marquee events where margins are high because demand significantly outstrips supply (Think about big games on the weekend against prime opponents or playoff games). Option two is more complicated. It likely takes time and makes you more visible to the team. Many clubs now employ revenue-sharing opportunities with brokers and use them to sell single-game tickets on the secondary market. Clubs may also leverage these secondary channels to flatten the markets.

Selling to brokers mitigates risk because you get the money that can be used for operations early. On the other hand, the amount of money we are dealing with could be large 52. However, there is a tradeoff. You no longer control your sales channels. Imagine if you could purchase airline tickets through secondary channels. Would airlines be able to price as effectively and dynamically?

Additionally, customer service could be an issue. It no longer resides with the club. What happens if your ticket doesn’t work? How do you fix it? This service issue becomes a brand problem. Recently, the quick proliferation of digital tickets has made this problem less relevant, but it does persist. There is also a technology component. What does the ticketing platform allow or disallow? While many of these technical problems will likely be solved in the future, they haven’t been eliminated.

Adding to the complexity of sales channels and inventory classes are price levels associated with specific locations:

- Premium areas might have amenities such as free F&B, better seats, club access, in-seat service, etc.

- Some seats may be in shaded areas

- Distance from the field or court may matter from an experiential and perceptual perspective

- The home field side of the park may be more attractive to some buyers

- The setting sun may make some seats less appealing

- Some people may want to sit in an area that is near specific food offerings or an ingress point close to their preferred parking location.

- Scoreboard sightlines may be an issue

All of these factors may not be considered, but some of them certainly should be. Product stratification is critical to maximizing revenue opportunity across customer expectations.

How do you determine willingness-to-pay? You should have historical data based on what people have paid for tickets for past events. It would be best to have sales levels associated with these prices for each ticket class and specific location. Other data might be much harder to capture. A stadium or arena might have dozens or even hundreds of different price levels. This is where cannibalization must be considered. You may need to learn what a price increase or decrease in one section might do to demand in another. The cross-price elasticity of demand between seating locations isn’t a trivial question. You can also deploy exciting techniques to help mitigate cannibalization, such as liner optimization53.

Another confounding factor is inventory levels. How do you know how much inventory is available? You might see that you sold seven seats in the dugout section, and they were sold against the Brewers on a Saturday night in July. However, you might not know that the inventory was on hold and unavailable for sale. Additionally, you might not know how many tickets were for sale on the secondary market. We aren’t even considering marketing efforts to promote the game.

Inventory control is a critical part of a pricing exercise. It shouldn’t be overlooked. Incentives to sell specific asset classes by the sales team can lead to sub-optimal inventory control protocols. For instance, the sales team may hold inventory for particular games to help hit group goals. When conducting a pricing exercise, ensure you understand how inventory may be allocated.

6.2 Understanding pricing mechanisms

When pricing tickets, you may be faced with an unresolvable goal.

We want to sell all of our available tickets at the highest price possible to optimize revenue

Is selling ten tickets at $100 for $1,000 in revenue equivalent to selling 100 tickets at $10 for $1,000 in revenue? The answer may be different depending on who you ask. We are going to look at price-response functions to get a quantitative perspective. Price response functions are fun to work with, and from an analytics perspective, you should enjoy deploying this type of analysis. Price response functions are handy, as is pointed out in “Pricing Segmentation and Analytics.” (Tudor Bodea 2012)

The most helpful feature of price-response functions is that, once estimated, they can be used to determine the price sensitivity of a product or how demand will change in response to a change in price. - Furguson and Bodea

What does a price-response function look like in practice.? Let’s say that you sell some tickets and build a chart of the results:

| Sales | Price |

|---|---|

| 20 | 25 |

| 30 | 28 |

| 35 | 29 |

| … | … |

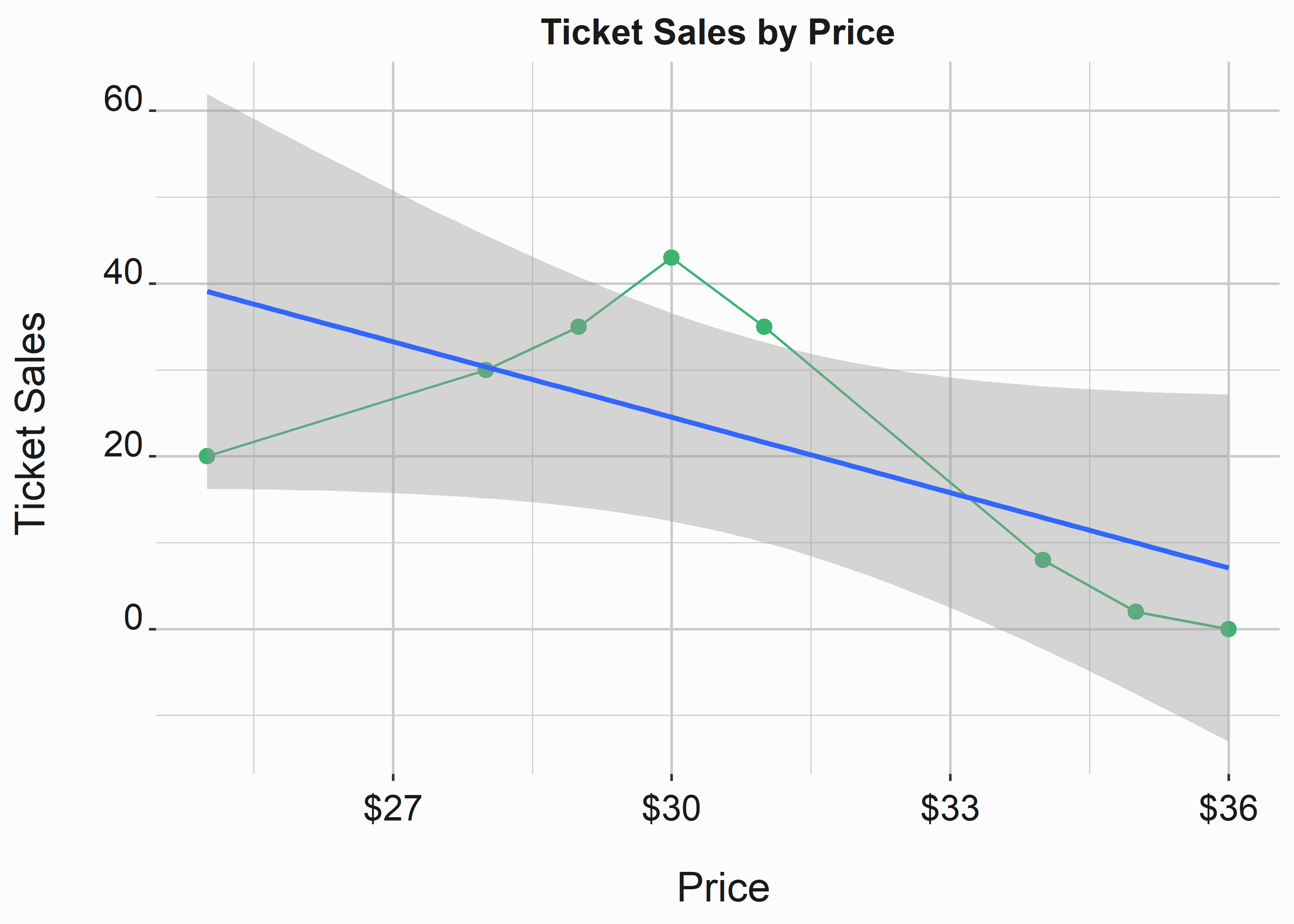

This table tells you how many tickets were sold at each price level. figure 6.1 represents this data:

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# The Price response function

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

library(tidyverse)

# Build a simple data set

sales <- tibble::tibble(

sales = c(20,30,35,43,35,8,2,0),

price = c(25,28,29,30,31,34,35,36)

)

x_label <- ('\n Price')

y_label <- ('Ticket Sales \n')

title <- ('Ticket Sales by Price')

line_sales <-

ggplot2::ggplot(data = sales,

aes(x = price,

y = sales)) +

geom_point(size = 2.5,color = 'mediumseagreen') +

scale_x_continuous(label = scales::dollar) +

xlab(x_label) +

ylab(y_label) +

ggtitle(title) +

graphics_theme_1 +

geom_line(color = "mediumseagreen") +

geom_smooth(method = 'lm')

Figure 6.1: Linear price response function

A linear model probably won’t do a great job forecasting sales at different price levels. We will also encounter diminishing returns at some point as we continue to raise prices. This graph is also missing some critical information. Let’s assume these prices represent one stadium section and only refer to single-game tickets. We’ll ignore that we don’t know when these tickets were sold, what channel they were sold through, or available inventory. Let’s also briefly talk about fitting distributions and price response functions. You could do this in many different ways, and we will look at a relatively simple example. the following examples are taken from “Pricing Segmentation and Analytics.” (Tudor Bodea 2012)

Typical examples of price response functions include:

Linear models:

\[\begin{equation} \ {d(p)} = {D} + {m}*{b} \end{equation}\]

Exponential models:

\[\begin{equation} \ d(p) = C*p^\epsilon \end{equation}\]

Logit models:

\[\begin{equation} \ {d(p)} = \frac{C*e^{a+b*p}}{1 + e^{a+b*p}} \end{equation}\]

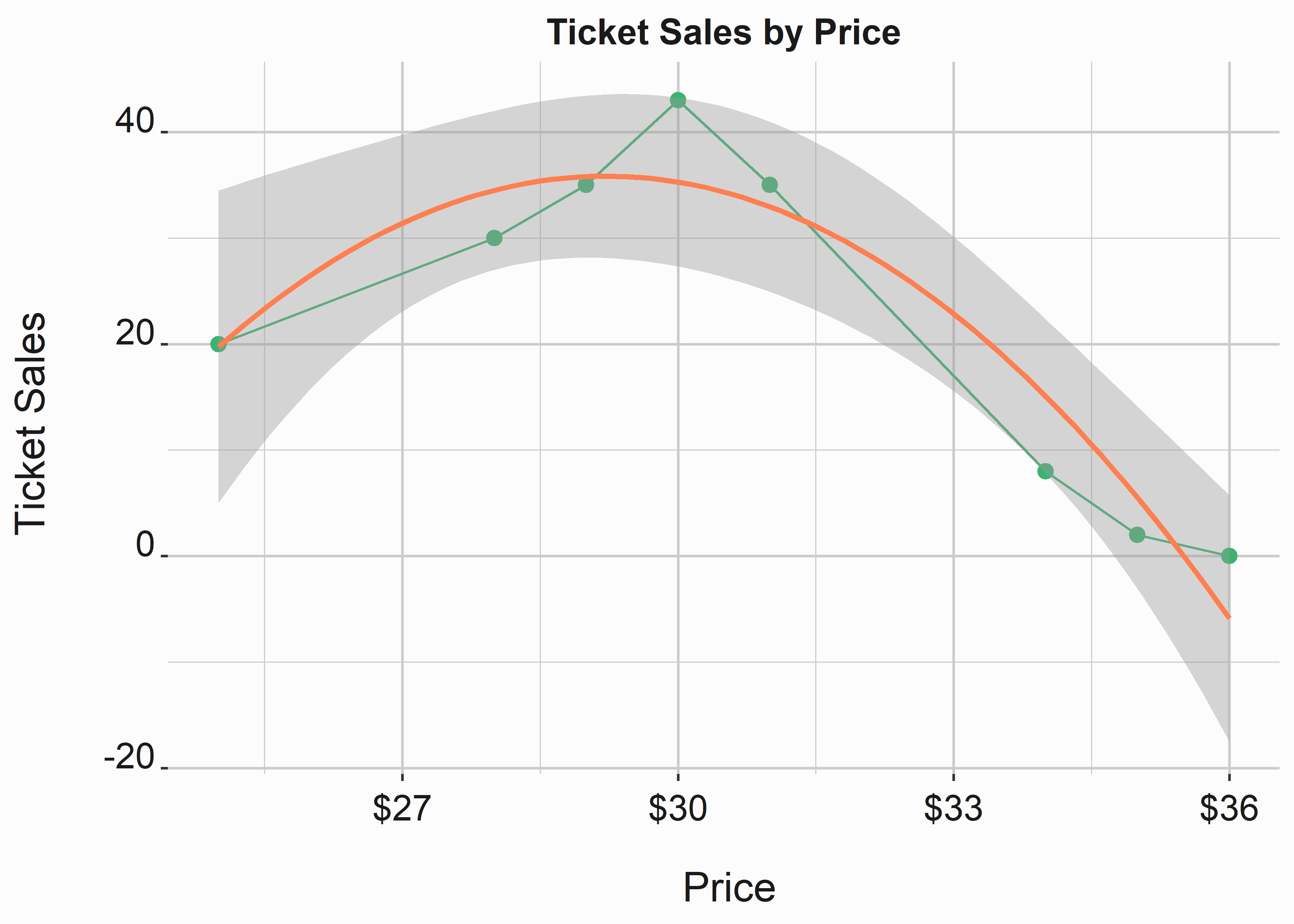

Let’s build a simple model that approximates our data better than a straight line. We can see that a linear model won’t fit this data as well as a curved one. It also doesn’t look constant or like a logit curve (two models you will likely encounter). So let’s try a simple polynomial.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# The Price response function

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

x_label <- ('\n Price')

y_label <- ('Ticket Sales \n')

title <- ('Ticket Sales by Price')

line_sales_poly <-

ggplot2::ggplot(data = sales,

aes(x = price,

y = sales)) +

geom_point(size = 2.5,color = 'mediumseagreen') +

scale_x_continuous(label = scales::dollar) +

xlab(x_label) +

ylab(y_label) +

ggtitle(title) +

graphics_theme_1 +

geom_line(color = "mediumseagreen") +

stat_smooth(method = "lm",color = 'coral',

formula = y ~ x + poly(x, 2)-1)

Figure 6.2: Polynomial price response function

This curve approximates our line relatively well. We could go through the exercise of finding the line that produces the best fit, but it isn’t necessary at this stage. Now that we are happy that a simple polynomial approximates our curve reasonably, what do we do? R provides several ways to evaluate fits. In the following example, we feed a polynomial function to the lm (linear model) function in R. We can then write a function f_get_Sales that we can use to return values from the line in figure 6.2. We’ll use the coefficients to complete our function.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Function to return sales based on price

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

fit <- lm(sales$sales~poly(sales$price,2,raw=TRUE))

f_get_sales <- function(new_price){

sales <- coef(fit)[1] +

(coef(fit)[2]*new_price + (coef(fit)[3] * new_price^2))

return(sales)

}

This is a poorly written function because it is hard-coded. The output would also be identical to using the predict function. We’ll look at it briefly when we apply this function to our data. It would be best to always generalize these sorts of functions when possible. We are using the hard-coded function so that you understand what is happening. Try using the following function and compare the output.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Function to return values from a polynomial fit

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

f_get_poly_fit <- function(new_var,dist_fit){

len_poly <- length(dist_fit$coefficients)

exponents <- seq(1:(len_poly-1))

value_list <- list()

for(i in 1:length(exponents)){

value_list[i] <- coef(dist_fit)[i+1] * new_var^exponents[i]

}

sum(do.call(sum, value_list),coef(dist_fit)[1])

}After we apply our function, we have an overfit price response function that we can use to forecast sales at different price levels. Since this concept may be unfamiliar to you, we’ll take a minute to explain what is going on here. fit <- lm(sales$sales~poly(sales$price,2,raw=TRUE)) is using the lm function (linear model) to fit a line to our data points. We aren’t necessarily looking for the best fit in this example. The function f_get_sales() takes the coefficients generated by the model stored in fit and builds an equation that we can use to plug price values into the equation to give us sales values (y) in terms of price (x). This might look scary, but it is just middle-school algebra.

The equation in our function sales <- coef(fit)[1] + (coef(fit)[2]*new_price + (coef(fit)[3] * new_price^2)) is nothing more than a rearranged linear equation with a second-degree exponent. A linear equation such as the equation that would fit the line in figure 6.1 would take this familiar form:

\[\begin{equation} \ {y} = {m}{x} + {b} \end{equation}\]

All we have done is rearrange this linear equation and add a second-degree exponent. The math now looks like this:

\[\begin{equation} \ {f(x)} = b + {m_1}{x} + {m_2}{x^2} \end{equation}\]

I conceptualize linear regression as a simple linear equation where each additional feature manipulates the slope of the line. This is the simplest way to think about it.

\[\begin{equation} \ ({m_1}{x} + {m_2}{x^2}) = {m}{x} \end{equation}\]

Now we can look at our estimates by applying our function to our original values.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Use f_get_sales to get modeled demand at each price level

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

old_prices <- c(25,28,29,30,31,34,35,36)

estimated_sales <- sapply(old_prices, function(x) f_get_sales(x))

# Either of these statements will produce the same output

# predict(fit,new_data = old_prices)

# sapply(old_prices, function(x) f_get_poly_fit(x,fit))| original_sales | estimated_sales | difference |

|---|---|---|

| 20 | 19.751628 | 0.2483715 |

| 30 | 34.504337 | -4.5043365 |

| 35 | 35.798031 | -0.7980312 |

| 43 | 35.279789 | 7.7202115 |

| 35 | 32.949608 | 2.0503916 |

| 8 | 15.087444 | -7.0874442 |

| 2 | 5.509515 | -3.5095147 |

| 0 | -5.880352 | 5.8803520 |

Additionally, we can feed other numbers directly to the function. For example, how many sales would we expect at a $26 price level?

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Use f_get_sales to get modeled demand at each price level

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

estimated_sales_new <- f_get_sales(26)| x | |

|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 26.48114 |

There are other tricks we can use on this equation. The highest point on the curve represents the maximum number of tickets sold at a particular price level. How do we find the price and the number of sales at this point? This is our raw equation:

\[\begin{equation} \ {f(x)} = -737.366 + {52.934}{x} + {-0.906}{x^2} \end{equation}\]

This is about as deep as we get into math in this book. We’ll see some tricky stuff in the chapter on operations, but this is as difficult as we get here. First, calculate the derivative of this function. If it has been a while since you’ve taken calculus, use a math engine such as Wolframalpha 54.

\[\begin{equation} \ \frac{dy}{dx} ({-737.366} + {52.934}{x} - {0.906}{x^2}) = {52.934} - {1.812}{x} \end{equation}\]

Setting the derivative = 0 and solving the equation will give you the price level at the highest point on the curve:

\[\begin{equation} \ f'(0) = {52.934} - {1.812}{x}; \end{equation}\]

Now we solve the equation:

\[\begin{equation} {26467}/{906} = {29.21} \end{equation}\]

The highest number of sales happen at a price of $29.21. So we can plug this number back into our original equation to get the y value.

\[\begin{equation} \ f(29.21) = -737.366 + {52.934}{29.21} + {-0.906}{29.21^2} = 35.8151054 \end{equation}\]

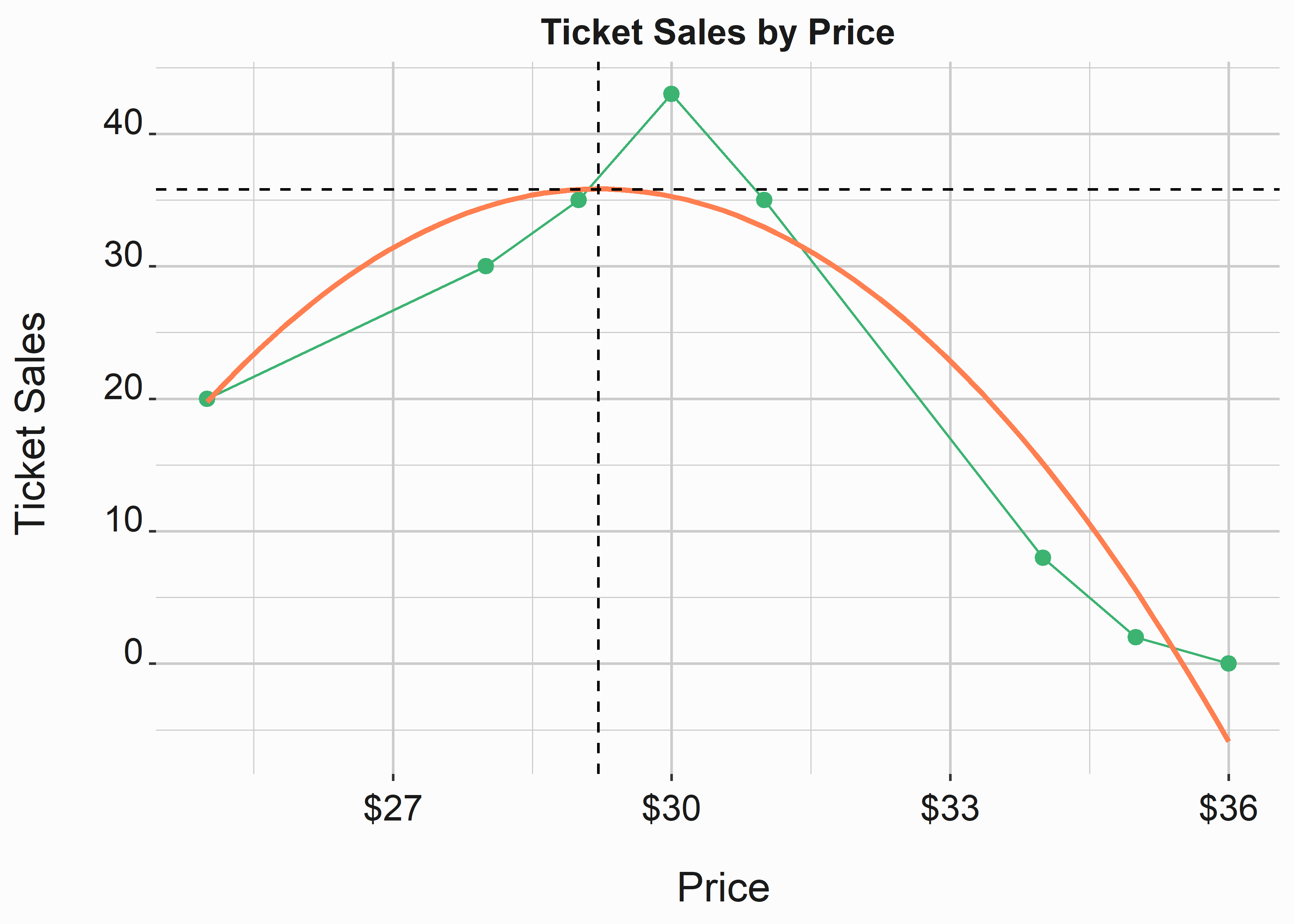

At $29.21, our model predicts 35.8151054 tickets to be sold. Let’s look at it in figure 6.3 and try to do some interpretation. As a side note, if you want to be a jerk and refuse to use some basic calculus, you could write a binary search function that traverses the function along your range of values and outputs minimums and maximums. Since we typically deal with whole numbers on a limited range, that approach is acceptable.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Demonstrate the highest point on the curve

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

x_label <- ('\n Price')

y_label <- ('Ticket Sales \n')

title <- ('Ticket Sales by Price')

line_sales_polyb <-

ggplot2::ggplot(data = sales,

aes(x = price,

y = sales)) +

geom_point(size = 2.5,color = 'mediumseagreen') +

scale_x_continuous(label = scales::dollar) +

xlab(x_label) +

ylab(y_label) +

ggtitle(title) +

graphics_theme_1 +

geom_line(color = "mediumseagreen") +

stat_smooth(method = "lm", color = 'coral',

formula = y ~ x + poly(x, 2)-1, se = F) +

geom_hline(yintercept = 35.8151054, lty = 2) +

geom_vline(xintercept = 29.21, lty = 2)

Figure 6.3: Finding a local maximum

This is great. We have identified the maximum number of tickets sold at any price level in our range. What does our revenue look like at specific prices according to this model?

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Look for optimum price levels

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

estimated_prices <- seq(from = 25, to = 35, by = 1)

estimated_sales <- sapply(estimated_prices,

function(x) f_get_sales(x))

estimated_revenue <- tibble::tibble(

sales = estimated_sales,

price = estimated_prices,

revenue = estimated_sales * estimated_prices,

totalSales = rev(cumsum(rev(sales)))

)| sales | price | revenue | totalSales |

|---|---|---|---|

| 19.751628 | 25 | 493.7907 | 288.421119 |

| 26.481135 | 26 | 688.5095 | 268.669491 |

| 31.398705 | 27 | 847.7650 | 242.188355 |

| 34.504337 | 28 | 966.1214 | 210.789651 |

| 35.798031 | 29 | 1038.1429 | 176.285314 |

| 35.279789 | 30 | 1058.3937 | 140.487283 |

| 32.949608 | 31 | 1021.4379 | 105.207495 |

| 28.807491 | 32 | 921.8397 | 72.257886 |

| 22.853436 | 33 | 754.1634 | 43.450395 |

| 15.087444 | 34 | 512.9731 | 20.596959 |

| 5.509515 | 35 | 192.8330 | 5.509515 |

Imagine that we must set prices for the product we have just modeled. How do you do it? We know where the revenue-maximizing number lives. Does it tell the entire story? Suppose you sell all the more expensive tickets for every price level. What does cumulative revenue look like in that case?

Let’s use a loop instead of an apply function and a defined function.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Look for optimum price levels

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

x <- 1

revenue <- list()

while(x <= nrow(estimated_revenue)){

revenue[x] <- estimated_revenue[x,2] * estimated_revenue[x,4]

x <- x + 1

}

estimated_revenue$totalRevenue <- unlist(revenue)| sales | price | revenue | totalSales | totalRevenue |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19.751628 | 25 | 493.7907 | 288.421119 | 7210.5280 |

| 26.481135 | 26 | 688.5095 | 268.669491 | 6985.4068 |

| 31.398705 | 27 | 847.7650 | 242.188355 | 6539.0856 |

| 34.504337 | 28 | 966.1214 | 210.789651 | 5902.1102 |

| 35.798031 | 29 | 1038.1429 | 176.285314 | 5112.2741 |

| 35.279789 | 30 | 1058.3937 | 140.487283 | 4214.6185 |

| 32.949608 | 31 | 1021.4379 | 105.207495 | 3261.4323 |

| 28.807491 | 32 | 921.8397 | 72.257886 | 2312.2524 |

| 22.853436 | 33 | 754.1634 | 43.450395 | 1433.8630 |

| 15.087444 | 34 | 512.9731 | 20.596959 | 700.2966 |

| 5.509515 | 35 | 192.8330 | 5.509515 | 192.8330 |

This is an interesting way to look at this problem. If you assume that you will sell every ticket that costs more than the price that you set, setting your prices at $25 would make you the most revenue. However, if you sold every ticket at the forecasted amounts, you earn more revenue: 8495.9703213. This simplistic example demonstrates the power of variable and dynamic pricing. There are also other considerations. If you could only set prices once, it might appear that the $25 price level would be the best. You earn the most ticket revenue and sell the most tickets. However, that is simply due to price elasticity and some assumptions we have made. What would you do if the season-ticket-holder price was $29? You now have brand considerations. When inventory is limited, it makes these decisions slightly more discrete.

6.3 Basics of forecasting

Forecasting is fundamental to setting prices, and there are many different ways to do it. However, this subject can also get very sophisticated. We’ll focus on a couple of basic approaches to forecasting that you would be confronted with if you were working for a club. Once again, while we will demonstrate how to approach these problems, we will focus on how to think about them. First, let’s create some sample data. You can also find this data in the FOSBAAS package by using FOSBAAS::past_season_data. You can use the functions to build different conditions into the data set if you would like to simulate different situations.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Generate past season's data

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

season_2022 <-

FOSBAAS::f_build_season(seed1 = 3000, season_year = 2022,

seed2 = 714, num_games = 81, seed3 = 366, num_bbh = 5,

num_con = 3, num_oth = 5, seed4 = 309, seed5 = 25,

mean_sales = 29000, sd_sales = 3500

)

season_2023 <-

FOSBAAS::f_build_season(seed1 = 755, season_year = 2023,

seed2 = 4256, num_games = 81, seed3 = 54, num_bbh = 6,

num_con = 4, num_oth = 7, seed4 = 309, seed5 = 25,

mean_sales = 30500, sd_sales = 3000

)

season_2024 <-

FOSBAAS::f_build_season(seed1 = 2892, season_year = 2024,

seed2 = 714, num_games = 81, seed3 = 366, num_bbh = 9,

num_con = 2, num_oth = 6, seed4 = 6856, seed5 = 2892,

mean_sales = 32300, sd_sales = 2900

)

past_season <- rbind(season_2022,season_2023,season_2024)Now let’s take a look at the data set that we have created.

| gameNumber | team | date | dayOfWeek | month | weekEnd | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 238 | 76 | FLA | 2024-09-22 | Sun | Sep | FALSE |

| 239 | 77 | FLA | 2024-09-23 | Mon | Sep | FALSE |

| 240 | 78 | FLA | 2024-09-24 | Tue | Sep | FALSE |

| 241 | 79 | LAA | 2024-10-04 | Fri | Oct | TRUE |

| 242 | 80 | LAA | 2024-10-05 | Sat | Oct | TRUE |

| 243 | 81 | LAA | 2024-10-06 | Sun | Oct | FALSE |

In this section, we will dive into regression in a little more rigorous fashion. Again, I highly recommend purchasing a book on regression, and my current favorite is “An R Companion to Applied Regression.” (John Fox 2019) by John Fox and Sanford Weisberg. It is convenient and doesn’t dwell on theory. There are also lots of statistical terms you will need to be familiar with to gain some proficiency with regression. Often, it is more important to understand the limitations of the tool you are using. A non-exhaustive list of terms you might run across might include:

- Hypothesis testing55

- Normality56

- Independence57

- linearity58

- Validation59

- Homoskedacity vs Heteroskedacity60

- Autocorrelation61

- Multicolinearity62

- Interaction terms63

- Omitted Variable Bias64

- Transformations65

- Endogeneity66

An unfortunate fact about working with sports data is that you will be living in a non-parametric world where rank order might be what is important. Some of the critical underlying assumptions about your data need to be met. There are specific ways to deal with some of these problems. However, we are not doing a clinical study, so there is no need to go through every test to ensure our model is durable. We will hit the high points and move on. You need to make sure that you are aware of how deep the ocean gets. We won’t get in over our heads.

As we said, we can approach forecasting in several ways, but there are two main types of forecasting approaches that we typically deploy:

- Top-down forecasts

- Bottom-up forecasts

A top-down forecast typically consists of macro-level factors such as team payroll and projected wins. These forecasts help compare potential across the entire league since we can understand the main components in advance. Bottom-up forecasts can vary in granularity but consist of more specific information such as the marketing schedule and specifics around scheduling and game attractiveness specific to your market. For example, this might mean rivalry games will be more attractive, and you can build that into your model. Let’s start by making a simple bottom-up forecast.

First, let’s create a treatment and control group to evaluate our model’s efficacy. In future chapters, we’ll perform these tasks with a couple of different packages and go more in-depth about applying modeling techniques to our data more rigorously. The following lines of code will create a training and test data set. This example uses standard R functions.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Build test and training set

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

samp <- round(0.05 * nrow(past_season),0)

set.seed(715)

rows <- sample(seq_len(nrow(past_season)),

size = samp)

train <- past_season[-rows, ]

test <- past_season[rows, ]In some of our earlier examples, we overfit the models. This is because we didn’t split the data into testing and training data. You could even partition the data further with a calibration set, but we’ll stick with a more straightforward training and test set for now.

Now we can build a simple linear model on the training data set. Why did we select the following values? Selecting values for your model can be involved. For now, let’s choose a few values that look reasonable. Variable selection can be involved, and creating parsimonious models (the simplest model that captures the most variance) is a best practice. Also, keep in mind that you are dealing with mixed data sets. Most of the regression examples you find deal with clean numerical data that is normally distributed. That is rarely the case in the wild.

The following sections won’t be exhaustive but will give you a crash course on what you must look for. They also use a realistic example that you would find working for a club.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Linear model for ticket sales

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

ln_mod_bu <- lm(ticketSales ~ promotion + daysSinceLastGame +

schoolInOut + weekEnd + team , data = train)

ln_mod_bu_sum <-

tibble::tibble(

st_error = unlist(summary(ln_mod_bu)[6]),

r_square = unlist(summary(ln_mod_bu)[8]),

adj_r_square = unlist(summary(ln_mod_bu)[9]),

f_stat = unlist(summary(ln_mod_bu)$fstatistic[1]))The standard summary for a model looks like this:

#>

#> Call:

#> lm(formula = ticketSales ~ promotion + daysSinceLastGame + schoolInOut +

#> weekEnd + team, data = train)

#>

#> Residuals:

#> Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

#> -10994.7 -2468.7 126.9 2504.1 8969.3

#>

#> Coefficients:

#> Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

#> (Intercept) 33357.39 2929.22 11.388 < 2e-16 ***

#> promotionconcert 127.09 1657.31 0.077 0.938953

#> promotionnone -5358.02 988.93 -5.418 1.71e-07 ***

#> promotionother -3721.18 1375.10 -2.706 0.007390 **

#> daysSinceLastGame 288.13 42.69 6.750 1.53e-10 ***

#> schoolInOutTRUE 4608.16 1037.41 4.442 1.47e-05 ***

#> weekEndTRUE 6397.82 610.61 10.478 < 2e-16 ***

#> teamATL 3135.03 3000.93 1.045 0.297417

#> teamBAL 4382.63 2925.33 1.498 0.135651

#> teamBOS 12751.52 3594.69 3.547 0.000484 ***

#> teamCHC 13193.89 3565.58 3.700 0.000278 ***

#> teamCIN 3659.22 3226.57 1.134 0.258101

#> teamCLE 2201.94 2906.84 0.758 0.449632

#> teamCOL 3057.71 3285.54 0.931 0.353142

#> teamCWS 3906.19 2985.27 1.308 0.192195

#> teamDET 3202.46 3267.54 0.980 0.328217

#> teamFLA 2833.12 2924.04 0.969 0.333750

#> teamHOU 10209.56 2947.13 3.464 0.000649 ***

#> teamKAN 5246.46 3732.75 1.406 0.161403

#> teamLAA 9102.40 2888.86 3.151 0.001875 **

#> teamLAD 12150.54 3198.52 3.799 0.000192 ***

#> teamMIN 1625.41 3708.86 0.438 0.661672

#> teamNYM 9879.64 3030.31 3.260 0.001306 **

#> teamOAK 1877.06 3741.10 0.502 0.616397

#> teamPHI 9450.28 3949.78 2.393 0.017645 *

#> teamSF 8185.73 3741.10 2.188 0.029813 *

#> teamTB 3212.49 3191.25 1.007 0.315305

#> teamTEX 4595.50 3069.58 1.497 0.135925

#> teamWAS 1036.66 3036.91 0.341 0.733192

#> ---

#> Signif. codes:

#> 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

#>

#> Residual standard error: 3900 on 202 degrees of freedom

#> Multiple R-squared: 0.6632, Adjusted R-squared: 0.6166

#> F-statistic: 14.21 on 28 and 202 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16What are we looking for with this output? First, you’ll need to hit the books. You’ll need to become more familiar with statistics speak.

- Estimate: These are the coefficients for the equation produced by this regression

- Std. Error: The standard error represents the average distance the estimates fall from the regression line.

- t value: This is the coefficient divided by the standard error

- Pr(>|t|): The p value. It will tell you if the variable is significant. How sure are we that the estimate falls within the confidence interval?

- Residual standard error: The larger this number, the less likely your model will be helpful.

- Multiple R-squared: How much variation is being explained by this model

- F-statistic: Is the model valid? Lower numbers here are bad

About 60% of the variance in ticket sales is explained by this simple model. Is that good? Not especially when we consider the standard error. Is there anything we can do to improve it? Let’s look at some regression diagnostics to help us evaluate our results. Additionally, you can run plot(ln_mod_bu) to get a few standard diagnostic plots.

We have cut the statistics down for brevity. That is why our summaries tend to look like this:

| st_error | r_square | adj_r_square | f_stat |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3899.53 | 0.6632383 | 0.6165585 | 14.20824 |

This is OLS regression, and certain assumptions need to be made about the underlying data. If they aren’t satisfied, your model may have some problems. The car package (Fox, Weisberg, and Price 2022) has some great tools to help you evaluate your models. We’ll use it to assess the model further.

6.3.1 Outliers and unusual data points

Linear regression is sensitive to outliers. Therefore, looking for data points that fall well outside the average range is always best. For instance, some games may have been rained out. Maybe a new promotion worked well. Something will create a unique data point or two. Sometimes it is appropriate to remove them.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Outliers test

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

library(car)

outliers <- car::outlierTest(ln_mod_bu)There only appears to be one outlier:

|

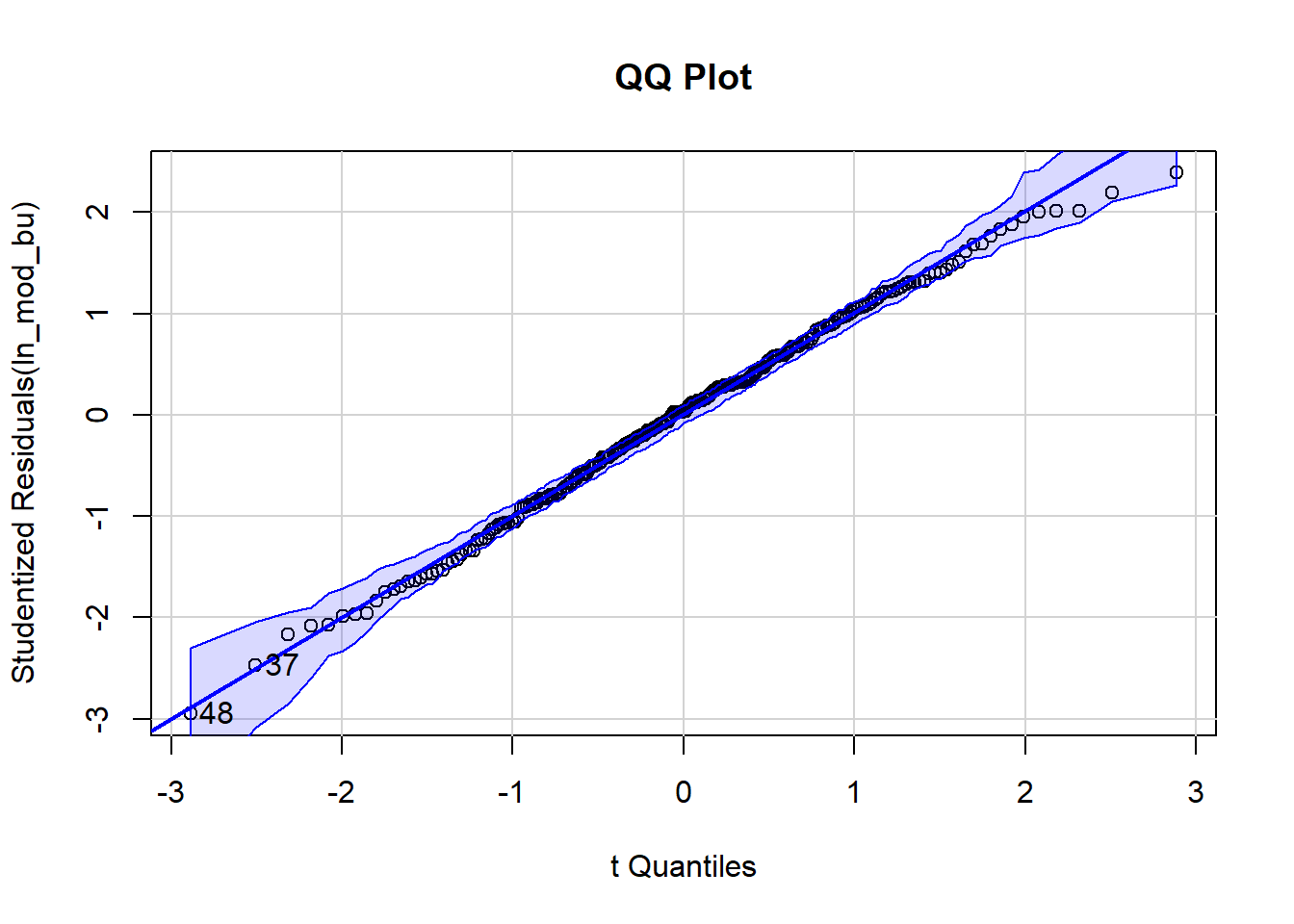

A QQ plot will help ensure our underlying assumptions around normality are satisfied. It demonstrates the “95% confidence envelope.”

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# QQPlot

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

qq <- car::qqPlot(ln_mod_bu, main="QQ Plot")

For the most part, our points fall on the line. A few points stray from it, and we can see our outlier (48) at the bottom. Extreme points can highly influence linear regression models. We’ll end up removing this point and rerunning the model.

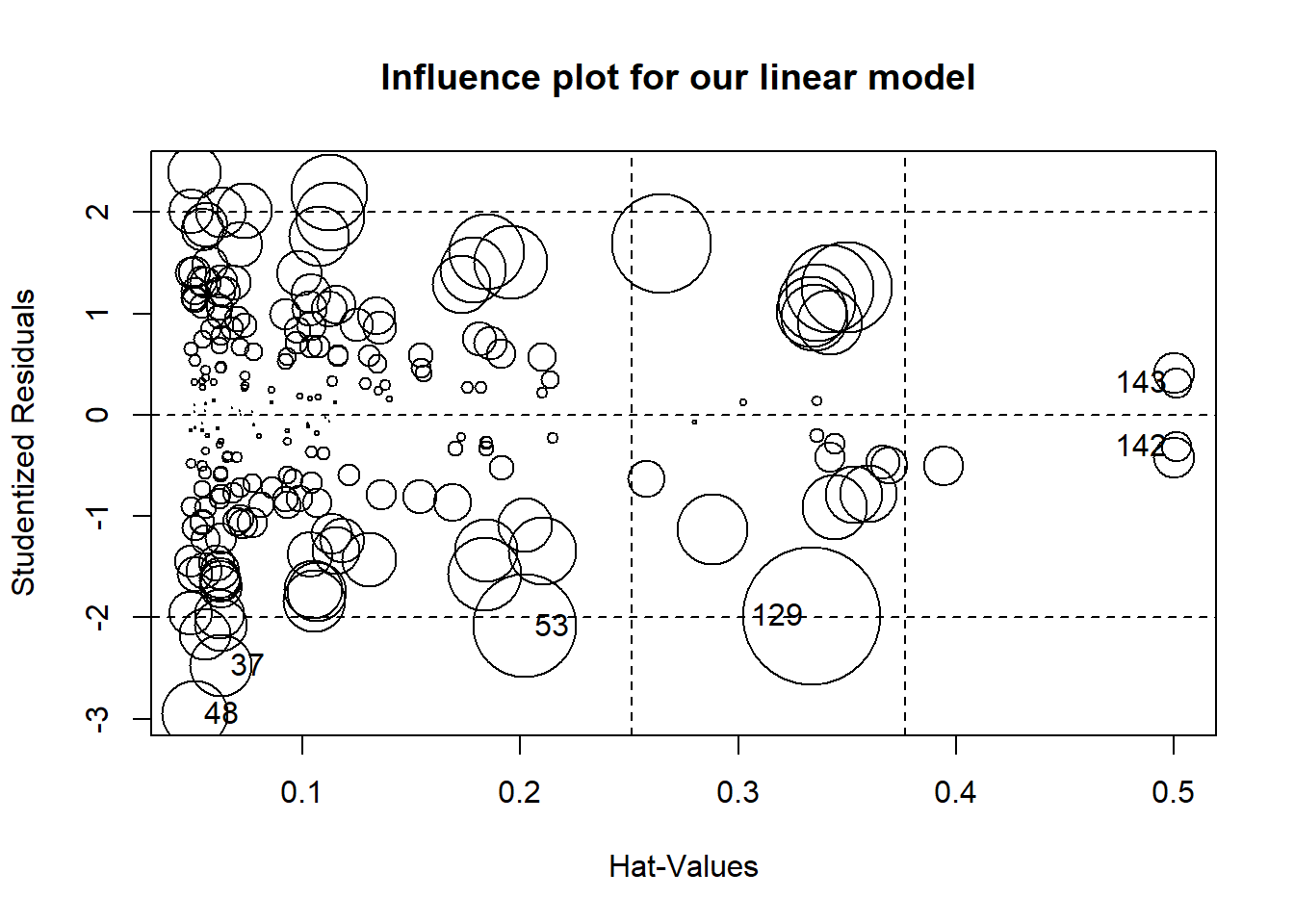

We can run an influence plot to combine several graphs you can see with plot(ln_mod_bu) .The bigger the circle, the larger Cooks Distance. Cooks distance has a mathematical definition but think of it as a way to identify influential points in the data.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Influence plot

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

ip <- car::influencePlot(ln_mod_bu, id.method="identify",

main="Influence plot for our linear model ")

Several points have an outsized influence on our model. We should evaluate them individually. It may be OK to remove them from our model if their values appear to be influenced by some exogenous factor we do not account for. Why might some of the points be influential? Perhaps it rained on a few of these dates and depressed ticket sales. It might be reasonable to exclude these dates from the analysis.

| StudRes | Hat | CookD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 37 | -2.474975 | 0.0625549 | 0.0137460 |

| 48 | -2.948634 | 0.0508503 | 0.0154727 |

| 53 | -2.087044 | 0.2021280 | 0.0374285 |

| 129 | -1.983284 | 0.3338126 | 0.0669910 |

| 142 | -0.313120 | 0.5010784 | 0.0034107 |

| 143 | 0.313120 | 0.5010784 | 0.0034107 |

Let’s remove some of the observations.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Remove outliers and view summary

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

past_season_clean <- past_season[-c(37,48,53,129,142,143),]

ln_mod_clean <- lm(ticketSales ~ promotion + daysSinceLastGame +

schoolInOut + weekEnd + team ,

data = past_season_clean)

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Save our model

# save(ln_mod_clean, file="ch6_ln_mod_clean.rda")

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

ln_mod_clean_sum <-

tibble::tibble(

st_error = unlist(summary(ln_mod_clean)[6]),

r_square = unlist(summary(ln_mod_clean)[8]),

adj_r_square = unlist(summary(ln_mod_clean)[9]),

f_stat = unlist(summary(ln_mod_clean)$fstatistic[1]))| st_error | r_square | adj_r_square | f_stat |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3820.177 | 0.6688948 | 0.624323 | 15.00711 |

We only get a modest improvement by removing some of the influential values. What else can we do? We can also look for interaction terms or transform our response. There are multiple ways to handle this. Additionally, you may not need to transform the data. In this case, we don’t see pronounced curvature in the data.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Transforming the data

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

summary(pw_mod <- car::powerTransform(ln_mod_clean))

#> bcPower Transformation to Normality

#> Est Power Rounded Pwr Wald Lwr Bnd Wald Upr Bnd

#> Y1 3.0383 3.04 2.2665 3.8101

#>

#> Likelihood ratio test that transformation parameter is equal to 0

#> (log transformation)

#> LRT df pval

#> LR test, lambda = (0) 71.19639 1 < 2.22e-16

#>

#> Likelihood ratio test that no transformation is needed

#> LRT df pval

#> LR test, lambda = (1) 30.40168 1 3.5122e-08You can also transform variables in your regression directly.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Directly transforming the data

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

ln_mod_log <-

lm(log(ticketSales) ~ promotion + daysSinceLastGame +

schoolInOut + weekEnd + team ,

data = past_season_clean)

ln_mod_log_sum <-

tibble::tibble(

st_error = unlist(summary(ln_mod_log)[6]),

r_square = unlist(summary(ln_mod_log)[8]),

adj_r_square = unlist(summary(ln_mod_log)[9]),

f_stat = unlist(summary(ln_mod_log)$fstatistic[1])

)| st_error | r_square | adj_r_square | f_stat |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1106438 | 0.6462896 | 0.5986747 | 13.57327 |

This makes the model worse. It also makes it more challenging to interpret. This phenomenon isn’t uncommon with the data you will find working in sports. We aren’t dealing with new medicines. We are dealing with dollars and cents. You don’t have to be as precise. However, precision helps! Often in business, you do the best you can. If you understand the limitations of what you have done, you’ll still be in good shape when it comes time to decide.

Let’s go ahead and apply our model to our testing data set. First, how well does it appear to approximate ticket sales in practice? Next, we’ll use the predict function to apply our predictions to our test data to observe how close the estimates fall to reality.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Apply predictions to our test data set.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

test$pred_tickets <- predict(ln_mod_clean,

newdata = test)

test$percDiff <-

(test$ticketSales - test$pred_tickets)/test$ticketSales

mean_test <- mean(test$percDiff)| x |

|---|

| -0.0239013 |

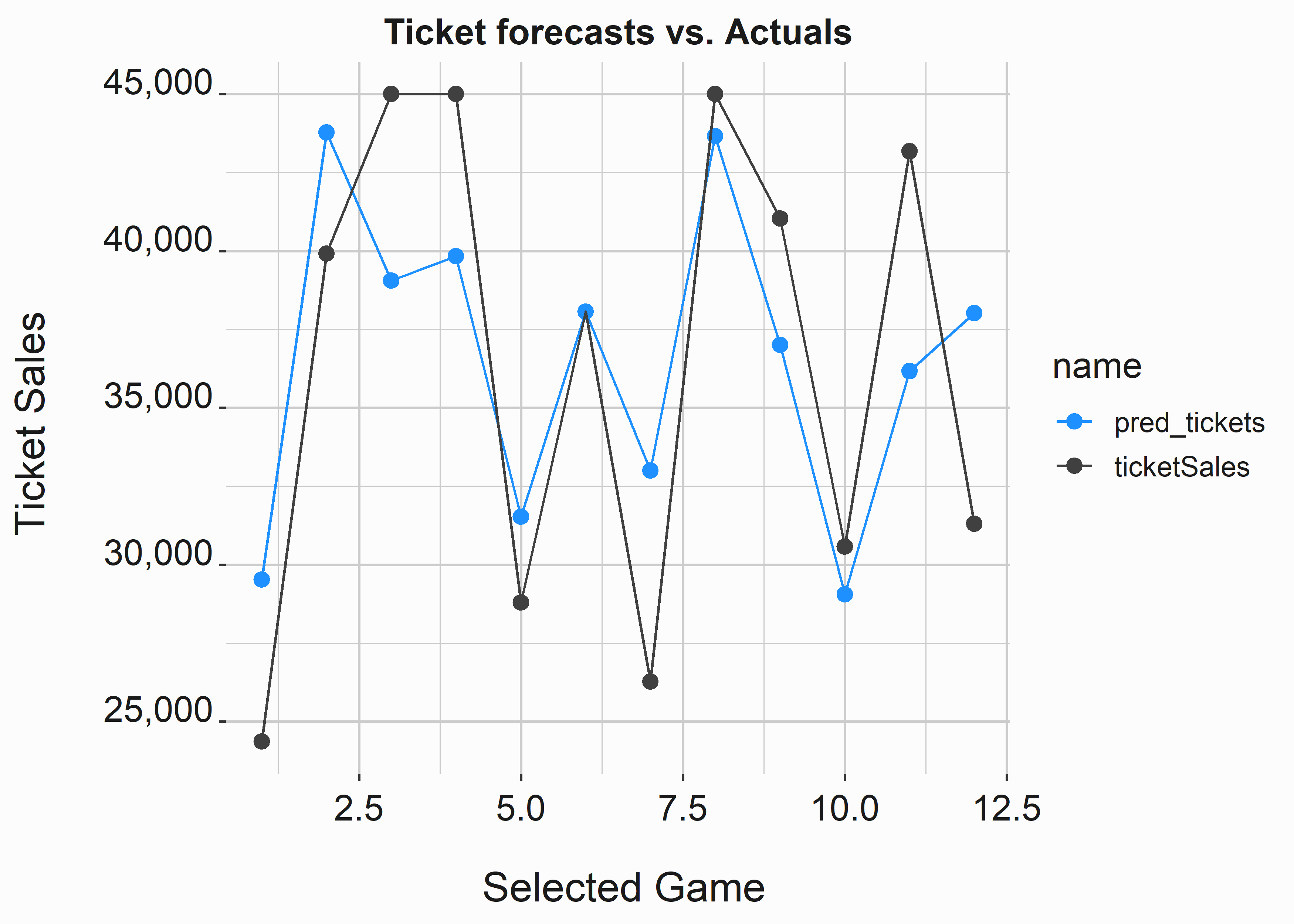

On average, we are about 2% off of the mark. Is that good? Maybe. It depends on what you are trying to accomplish. Let’s take a look at this error on a graph.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Apply predictions to our test data set.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

test_line <- test

test_line$order <- seq(1:nrow(test))

test_line <- tidyr::pivot_longer(test_line,

cols = c('ticketSales','pred_tickets'),

values_transform = list(val = as.character))

x_label <- ('\n Selected Game')

y_label <- ('Ticket Sales \n')

title <- ('Ticket forecasts vs. Actuals')

line_est <-

ggplot2::ggplot(data = test_line,

aes(x = order,

y = value,

color = name)) +

geom_point(size = 2.5) +

geom_line() +

scale_color_manual(values = palette) +

scale_y_continuous(label = scales::comma) +

xlab(x_label) +

ylab(y_label) +

ggtitle(title) +

graphics_theme_1

Overall, our error is relatively low. However, we can see that while the average error is low, the point estimates can vary considerably. Can I apply this model to new data? I believe so. However, I would look for other predictors that might improve my model. Removing season tickets may help. Unfortunately, the further away from the season, the more blunt your estimates tend to be. You won’t have gambling odds, and you may not have a promotional schedule. You need to pull insignificant teams from the model to be able to use them to make a forecast. You’ll have to guess. You’ll often have to settle for “good enough.”

This top-down approach to forecasting sales and analyzing prices is helpful in certain circumstances and has many applications. However, our following example will cover a bottom-up approach.

6.3.2 Analyzing a schedule and ranking games

How much of an impact does a schedule have on a team’s financial success? What other factors should be considered? For a sport like professional baseball, ticket sales are the most crucial component of revenue generation. Almost every additional revenue stream is derived from sales. Let’s take a look at some schedule data to begin to frame this problem. I like to take an ensemble approach to these problems. In this case, we will do the same thing in two different ways. First, we will evaluate games based on their attractiveness to fans. This bottom-up approach will use secondary market purchases to estimate each game’s attractiveness.

6.3.2.1 Utilizing transaction data

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Secondary market data, manifest, and sales data

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

sm <- FOSBAAS::secondary_data

man <- FOSBAAS::manifest_data

sea <- FOSBAAS::season_data

sea$gameID <- seq(1:nrow(sea))As always, let’s begin by understanding the underlying data structure.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Secondary market data, manifest, and sales data

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

head(sm)[c(1,2,7,9)]| seatID | custID | price | secondayrPrice |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9010 | N22J8UPWACNO | 54.0 | 60.51 |

| 20950 | II3IGIN0PY15 | 30.0 | 37.11 |

| 16 | HL1LS8PNUJXU | 190.0 | 174.34 |

| 30607 | XA8PY4QVWBMF | 20.7 | 24.30 |

| 2399 | RTC7OFV5BUBL | 103.5 | 143.24 |

| 10250 | EP37BTOALOCY | 54.0 | 77.03 |

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Secondary sales by section

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

sm_man <- left_join(sm,man, by = 'seatID')

avg_price_comps <-

sm_man %>% dplyr::select(gameID,price,singlePrice,tickets) %>%

na.omit() %>%

dplyr::group_by(gameID) %>%

dplyr::summarise(meanSec = mean(price),

meanPri = mean(singlePrice),

tickets = sum(tickets))| gameID | meanSec | meanPri | tickets |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 40.35872 | 44.19619 | 3101 |

| 2 | 40.72825 | 44.16555 | 3520 |

| 3 | 39.96533 | 43.85449 | 3186 |

| 4 | 40.02371 | 43.43759 | 3484 |

| 5 | 39.83003 | 43.48523 | 3293 |

| 6 | 41.42634 | 45.21318 | 3347 |

Now we can look by game to see how many transactions happened and what was spent. We can join this table to our original season data table and then see if we can use a regression to accurately predict which games commanded higher prices on the secondary market. This data wasn’t created to be linked, so we will alter it. We’re going to do this so the results look realistic.

We’ll create a scaled ticket sales coefficient and add it to the mean secondary price.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Adjust secondary to reflect primary

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

sea_adj <- left_join(sea,avg_price_comps, by = "gameID")

adj_coef <- scale(sea_adj$ticketSales)

sea_adj$meanSecAdj <- sea_adj$meanSec + (adj_coef * 10)Now let’s build a model on this data.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Adjust secondary to reflect primary

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

ln_mod_sec <-

lm(meanSecAdj ~ promotion + daysSinceLastGame +

schoolInOut + weekEnd + team ,

data = sea_adj)

ln_mod_sec_sum <-

tibble::tibble(

st_error = unlist(summary(ln_mod_sec)[6]),

r_square = unlist(summary(ln_mod_sec)[8]),

adj_r_square = unlist(summary(ln_mod_sec)[9]),

f_stat = unlist(summary(ln_mod_sec)$fstatistic[1])

)| st_error | r_square | adj_r_square | f_stat |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3.071083 | 0.9193594 | 0.9075117 | 77.5983 |

This model works well. It explains about 90% of the variance in secondary market prices. Of course, this model is overfitted, but you get the point. Let’s assume we put more rigor into this example and get to the application.

6.3.3 Applying our models to a new data set

Now that we have a model constructed, how do we apply it to new data? What are we doing with it? First, let’s evaluate the model’s results against themselves to create an event score that can be used to think about our promotion schedule. Here is how we can do it.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Create data for a new season

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

season_2025 <-

FOSBAAS::f_build_season(seed1 = 755, season_year = 2025,

seed2 = 714, num_games = 81, seed3 = 366, num_bbh = 5,

num_con = 3, num_oth = 7, seed4 = 366, seed5 = 1,

mean_sales = 0, sd_sales = 0

)Our new data uses seed2 = 714. If I type View(f_build_season), I can see that seed2 controls the teams that are selected for the schedule. What happens if you use a different seed2? You might get factor levels that you didn’t anticipate. The model is unable to make a prediction on these values. What do you do here? The easiest thing to do is to remove the offending factor levels. You could also make them analogs and substitute in a like-factor.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Apply model output to new data set

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

season_2025$predTickets <- predict(ln_mod_clean,

newdata = season_2025)

season_2025$predPrices <- predict(ln_mod_sec,

newdata = season_2025)| variable | classe | first_values |

|---|---|---|

| gameNumber | integer | 1, 2 |

| team | character | FLA, FLA |

| date | character | 2025-03-27, 2025-03-28 |

| dayOfWeek | integer | Thu, Fri |

| month | integer | Mar, Mar |

| weekEnd | logical | FALSE, TRUE |

| schoolInOut | logical | FALSE, FALSE |

| daysSinceLastGame | double | 50, 1 |

| openingDay | logical | TRUE, FALSE |

| promotion | character | none, none |

| ticketSales | double | 0, 0 |

| season | double | 2025, 2025 |

| predTickets | double | 44958.4169736301, 37738.5433636259 |

| predPrices | double | 48.6265858538348, 36.6916490543523 |

Now that we have predictions around ticket sales, we can build some event scores from them. This is the simple part.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Build event scores

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

season_2025$eventScoreA <-

as.vector(scale(season_2025$predTickets) * 100)

season_2025$eventScoreB <-

as.vector(scale(season_2025$predPrices) * 100)

season_2025$eventScore <-

season_2025$eventScoreA + season_2025$eventScoreB

season_2025 <- season_2025[order(-season_2025$eventScore),]| variable | classe | first_values |

|---|---|---|

| gameNumber | integer | 79, 52 |

| team | character | LAA, DET |

| date | character | 2025-09-13, 2025-07-25 |

| dayOfWeek | integer | Sat, Fri |

| month | integer | Sep, Jul |

| weekEnd | logical | TRUE, TRUE |

| schoolInOut | logical | FALSE, TRUE |

| daysSinceLastGame | double | 1, 10 |

| openingDay | logical | FALSE, FALSE |

| promotion | character | bobblehead, none |

| ticketSales | double | 0, 0 |

| season | double | 2025, 2025 |

| predTickets | double | 49358.3881551301, 46644.2609827693 |

| predPrices | double | 56.1825828148457, 54.144879836537 |

| eventScoreA | double | 239.600940080784, 184.096168478207 |

| eventScoreB | double | 230.93966856631, 206.238484837644 |

| eventScore | double | 470.540608647093, 390.334653315851 |

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Observe differences in event scores

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

library(ggplot2)

season_2025$order <- seq(1:nrow(season_2025))

x_label <- ('\n Game')

y_label <- ('Event Scores \n')

title <- ('Ordered event scores')

line_est_es <-

ggplot2::ggplot(data = season_2025,

aes(x = order,

y = eventScore)) +

geom_point(size = 1.3,color = 'dodgerblue') +

geom_line() +

scale_color_manual(values = palette) +

scale_y_continuous(label = scales::comma) +

xlab(x_label) +

ylab(y_label) +

ggtitle(title) +

graphics_theme_1

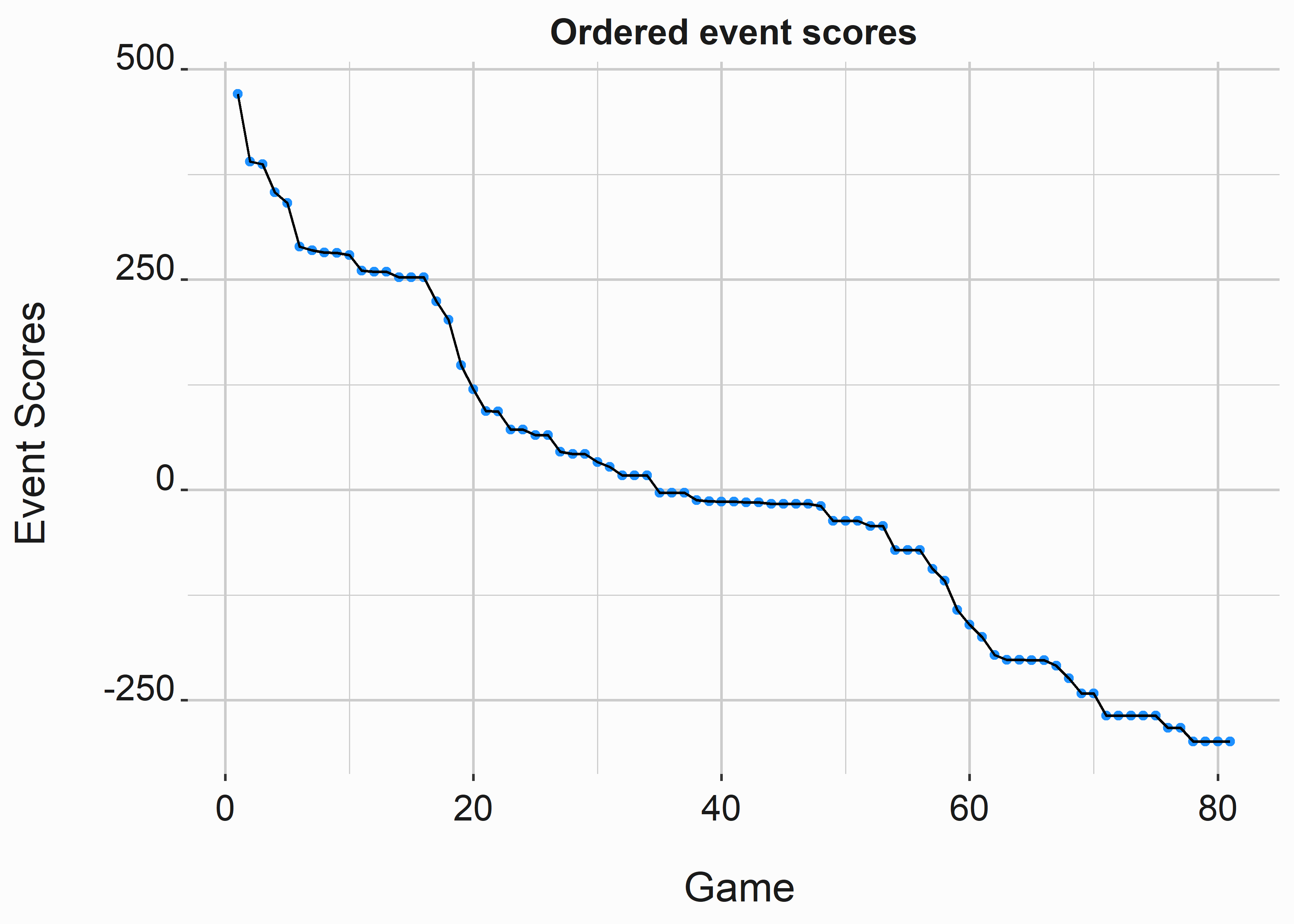

We can see that there are groupings of games that have similar levels of attractiveness. Although many games appear more attractive than others, they may have also been priced higher. Based on this demand attractiveness, we can progressively price our games with the highest anticipated demand receiving higher prices.

Let’s cluster like games together based on their event scores. We’ll use the kmeans function to group our games. You’ll see kmeans getting used quite a bit. It is relatively simple to understand and does a good job of discriminating numerical data sets.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Kmeans clustering on event scores

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

set.seed(715)

clusters <- kmeans(season_2025$eventScore,6)

season_2025$cluster <- clusters$cluster

#write.csv(season_2025,'season_2025.csv',row.names = F)Now let’s look at some summary stats for the groups.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Summary statistics

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

library(dplyr)

season_summary <- season_2025 %>%

group_by(cluster) %>%

summarise(mean = mean(eventScore),

median = median(eventScore),

sd = sd(eventScore),

n = n()) %>%

arrange(desc(mean))

knitr::kable(season_summary,caption = "Summary stats by cluster",

align = 'c',format = "markdown",padding = 0)| cluster | mean | median | sd | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 388.62293 | 387.30144 | 50.45311 | 5 |

| 3 | 260.07078 | 259.18470 | 25.11326 | 13 |

| 5 | 60.71921 | 55.16080 | 38.29457 | 16 |

| 4 | -32.95683 | -16.52499 | 29.59564 | 24 |

| 2 | -191.62441 | -202.08667 | 24.68114 | 10 |

| 6 | -276.02569 | -268.42818 | 20.09275 | 13 |

We now have several groups of games that we can evaluate. We can use these groups in various ways. One way is to look for games that need help. Let’s see if a promotion impacted sales. We’ll do this in chapter 8. You now have a data set that gives you a good idea of how attractive each game is against every other game. However, pricing is much more complex in practice. Reference pricing plays a part in how you might price. The main idea here is that we will price our games based on their attractiveness. We are using attractiveness as a proxy for demand.

How can we improve this bottom-up forecast? We can begin to layer other data onto it. What data are we looking for? There are several pieces of data that we can use:

- The number of season tickets that we have sold and anticipate selling

- Available inventory by game and how it is allocated

- prices paid and volume for each ticket class

You are likely to have imperfect conditions for setting prices. Additionally, our model could be more compelling. How could we improve our model? In practice, we prefer an ensemble approach. You can use that data to access a liquid market, like the secondary market, with many transactions at different prices.

6.4 Leveraging qualitative data

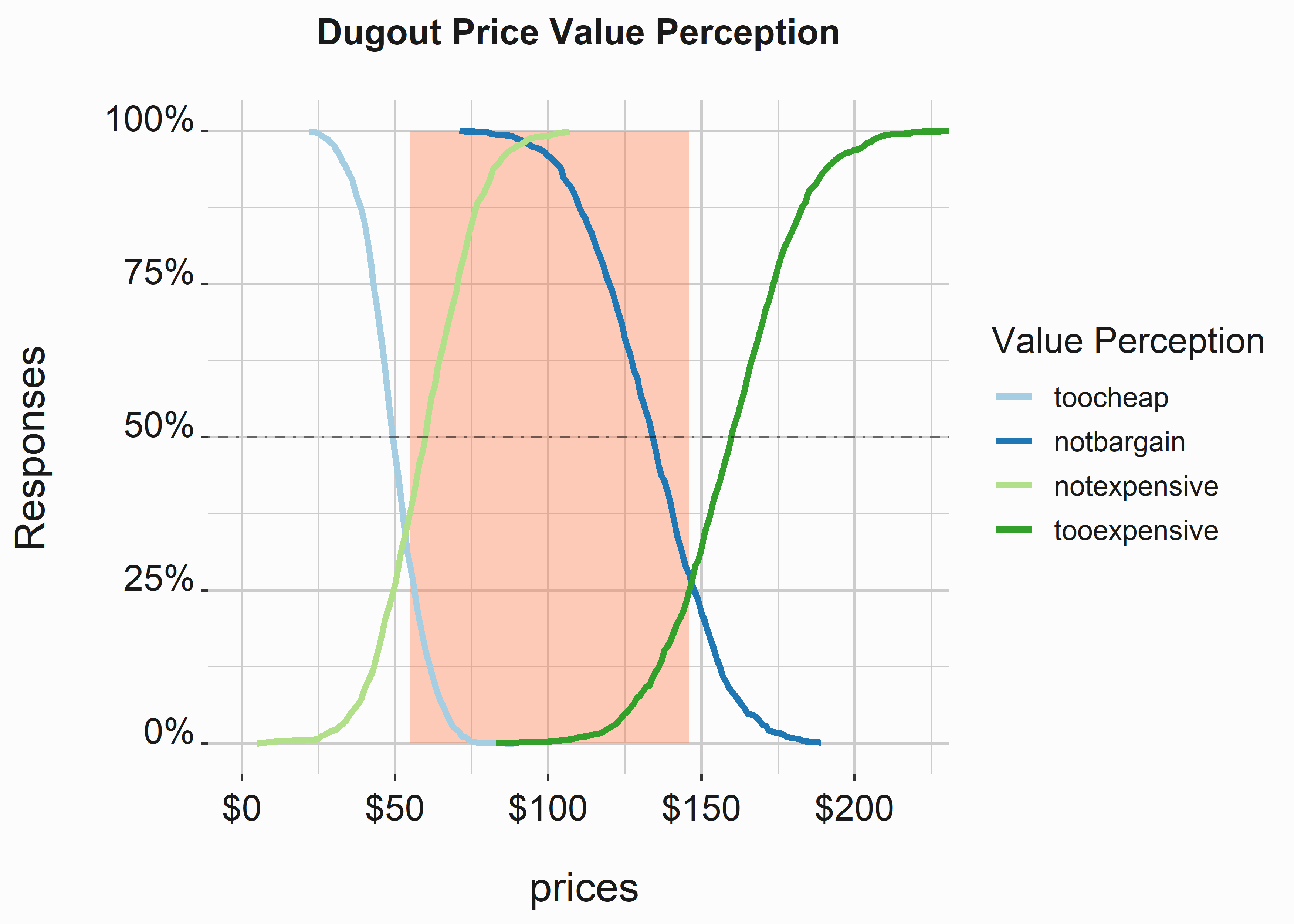

Leveraging surveys for pricing support may or may not have utility. There are two principal methodologies that we have deployed in practice:

- Van Westendorp analysis

- Conjoint

Both of these techniques are supported by survey tools such as Qualtrics. Conjoint analysis can be complex, and understanding it is well outside the scope of this book. Let’s look at a Van Westendorp survey and talk about how it can be helpful.

First, we need to create some survey data.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Create Van Westendorp survey data

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

vw_data <- data.frame(matrix(nrow = 1000, ncol = 6))

names(vw_data) <- c('DugoutSeats', 'PriceExpectation',

'TooExpensive', 'TooCheap',

'WayTooCheap', 'WayTooExpensive')

set.seed(715)

vw_data[,1] <- 'DugoutSeats'

vw_data[,2] <- round(rnorm(1000,100,10),0)

vw_data[,3] <- round(rnorm(1000,130,20),0)

vw_data[,4] <- round(rnorm(1000,60,15),0)

vw_data[,5] <- round(rnorm(1000,50,10),0)

vw_data[,6] <- round(rnorm(1000,160,20),0)| DugoutSeats | PriceExpectation | TooExpensive | TooCheap | WayTooCheap | WayTooExpensive |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DugoutSeats | 100 | 115 | 57 | 39 | 170 |

| DugoutSeats | 113 | 147 | 69 | 52 | 129 |

| DugoutSeats | 102 | 169 | 67 | 51 | 163 |

| DugoutSeats | 103 | 134 | 72 | 54 | 148 |

| DugoutSeats | 99 | 88 | 46 | 37 | 163 |

| DugoutSeats | 83 | 123 | 77 | 59 | 145 |

Like many statistical tools that you will find, there is a package for analyzing Van Westendorp data. Let’s start by doing it more manually. We’ll have to do a little prep work. First, let’s build a new dataframe with some slightly different terminology.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Empirical cumulative distribution function

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

library(Hmisc)

dat <- data.frame(

"toocheap" = vw_data$WayTooCheap,

"notbargain" = vw_data$TooExpensive,

"notexpensive" = vw_data$TooCheap,

"tooexpensive" = vw_data$WayTooExpensive

)

a <- Ecdf(dat$toocheap,what="1-F",pl=F)$y[-1]

b <- Ecdf(dat$notbargain, pl=F)$y[-1]

c <- Ecdf(dat$notexpensive,what = "1-F", pl=F)$y[-1]

d <- Ecdf(dat$tooexpensive,pl=F)$y[-1]The Ecdf function from the Hmisc package will give you coordinates for the cumulative distribution. We’ll use the reshape2 (Wickham 2020) package to melt the data frame. This package helps pivot data, and the results will be identical to using tools in the tidyr package we have already seen.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Build data set for creating graphic

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

library(reshape2)

ecdf1 <- data.frame(

"variable" = rep("toocheap",length(a)),

"ecdf" = a,

"value" = sort(unique(dat$toocheap)))

ecdf2 <- data.frame(

"variable" = rep("notbargain",length(b)),

"ecdf" = b,

"value" = sort(unique(dat$notbargain),decreasing = T))

ecdf3 <- data.frame(

"variable" = rep("notexpensive",length(c)),

"ecdf" = c,

"value" = sort(unique(dat$notexpensive),decreasing = T))

ecdf4 <- data.frame(

"variable" = rep("tooexpensive",length(d)),

"ecdf" = d,

"value" = sort(unique(dat$tooexpensive)))

dat2 <- rbind(ecdf1,ecdf2,ecdf3,ecdf4)

dat <- melt(dat)

dat <- merge(dat,dat2,by=c("variable","value"))Now we are ready to view our graph.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Graph the results

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

require(ggplot2)

require(scales)

require(RColorBrewer)

Paired <- RColorBrewer::brewer.pal(4,"Paired")

g_xlab <- '\n prices'

g_ylab <- 'Responses \n'

g_title <- 'Dugout Price Value Perception\n'

vw_gaphic <-

ggplot(dat, aes(value, ecdf, color=variable)) +

annotate("rect", xmin = 55, xmax = 146,

ymin = 0, ymax = 1,

alpha = .4, fill = 'coral') +

geom_line(size = 1.2) +

scale_color_manual(values = Paired,

name = 'Value Perception') +

xlab(g_xlab) +

ylab(g_ylab) +

ggtitle(g_title) +

scale_y_continuous(labels = percent) +

scale_x_continuous(labels = dollar) +

coord_cartesian(xlim = c(0,220),ylim= c(0,1)) +

geom_hline(yintercept = .5,

lty=4,

alpha = .5) +

graphics_theme_1

We can also use the pricesensitivitymeter package to produce our analysis more quickly.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Duplicate work with a library

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

library(pricesensitivitymeter)

price_sensitivity <- psm_analysis(

toocheap = "WayTooCheap",

cheap = "TooCheap",

expensive = "TooExpensive",

tooexpensive = "WayTooExpensive",

data = vw_data,

validate = TRUE)The price_sensitivity object makes it easy to explore the data.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Explore price sensitivity data

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

ps <-

tibble::tibble(lower_price = price_sensitivity$pricerange_lower,

upper_price = price_sensitivity$pricerange_upper)| lower_price | upper_price |

|---|---|

| 55 | 146 |

You can also produce the same plot that we have already created. The plotting mechanism leverages ggplot2 so you can override the look. We now have some qualitative data on price sensitivity. This doesn’t represent a willingness to pay, but it does help us conceptualize a range of prices that might be appropriate.

6.5 Implementing revenue management strategies in sports

These techniques are becoming increasingly commoditized. The mechanisms for forecasting and pricing are well understood and widely deployed. Additionally, ticketing platforms and markets are already working together to enable instantaneously deploying changes across multiple markets. We have already covered the primary considerations, but we didn’t talk about all of them:

- Brand and consumer equity

- Setting initial prices

- Automatically adjusting prices

- Controlling cannibalization

- Public relations and perception

- The perceived fairness of raising prices

Lowering prices can negatively impact perception and brand equity in the long term. Concepts such as prospect theory explain how changes in utility are asymmetric between gains and losses. (Tudor Bodea 2012) If someone feels they missed out because of your pricing policy, it will have deleterious impacts. Additionally, not all price changes may be perceived as fair. Keep behavioral economics in mind as you deploy your pricing strategy.

Initial prices are challenging to set, and reference prices are potent mechanisms. If you develop a new product (such as a premium seating area), consider the value proposition carefully. Some in-market competitive intelligence may be useful here. However, don’t rely on a pro forma.

How do you evaluate prices and deploy them? Setting an internal mechanism with sales, marketing, and operations is best. Pricing is one of the single-most vital sales and revenue influencers. You’ll want the right people at the table. You’ll also want to make sure the right technology is deployed. How does the price get to the market? How is it updated on the website? Do you have policies about how much or little specific tickets may cost?

Additionally, your inventory control protocols may influence your decisions. If I raise prices in one section, how does it impact demand in another? This is a fundamental component of pricing. Your price levels are linked. You can explain these links through systems of equations. There are multiple ways to approach these problems.

Finally, how will people respond to prices? It will depend on a number of factors such as demand, success, and markets. Exploiting opportunities is only sometimes appropriate. Qualitative research may help. You can deploy conjoint surveys and other research tools to help gauge how fans will respond to products or changes in price. Taking an ensemble approach to pricing is a recommended approach.

6.6 Key concepts and chapter summary

Getting pricing right is a key component of an integrated marketing mix strategy. Pricing has several quantitative and qualitative features. We covered several concepts:

- Inventory control

- Mechanical price controls

- More in-depth regression

- Forecasting and schedule analysis

- Event scoring

- Qualitative research

We only skimmed this broad subject, but you know, understand some of the basics of this very complex subject.

- Inventory can be complex, and people may perceive inventory in different ways. Understanding the differences between inventory is essential if you are building a discreet-choice model.

- The mechanics for determining prices tend to rely on mathematical models. These models can be adjusted to promote sales or maximize revenue generation. These goals may be inclusive or exclusive.

- Regression can be rigorous. To be confident in the results, you’ll need to spend some time methodically evaluating the model. Get a book on regression and make sure that you understand it enough to use it correctly.

- Schedules can play an outsized role in revenue generation. We walked through how to evaluate a schedule. This will be useful when marketing wants to build promotions for games with less demand.

- We covered how to use a Van Westendorp analysis to help us understand how people perceive inventory and prices.