9 Research

This chapter will discuss different research techniques to understand consumer preferences and composition. Ordinary people should recoil from research. It is tedious, painful, typically repetitive, and opens you up to scrutiny. Moreover, research is complex, and extensive experience in the field is difficult to acquire. Finally, it is a vast subject; you must understand it to be a complete analyst.

One of the main issues that you will face with it is that results from research projects are often only considered in a cursory fashion. The person who understands the results the best will be the designer and analyst. This is partly because many internal consumers are only interested in a narrow band of concerns. It can be discouraging when so much work goes into a project that can easily be disregarded.

Furthermore, proper research is an enormous topic. In chapters 5 and 6, we mention that writing an entire book on pricing and segmentation would be easy due to the breadth of the subjects. It would be easy to fill multiple volumes on consumer research. You can find many of these tomes on ebay or other sites traded at a significant discount. Purchase a few of them to add to your library. If you continue reading this chapter, we’ll discuss a few books I have used. Primary research techniques have mostly stayed the same for a long time, and having a few references is advised. This chapter will discuss two main topics:

- The basics of experiment design and hypothesis testing

- Planning and designing surveys

We’ll only be able to cover a sliver of topics and techniques you will likely face at some point in your career. We have already discussed ANOVA and other mechanisms to analyze experiments, but we didn’t discuss how those experiments should be designed. The term statistical significance is often mentioned in the context of surveys. The concept of statistical significance often needs to be better understood. It is used in a narrow context around hypothesis testing and is a mathematical artifact. It doesn’t mean that a survey is good and valuable. We’ll discuss it in some detail a little later.

I included experiment design here because it is a topic where most people need more experience. Indeed, many business leaders aren’t well versed in research in any practical way and have a difficult time navigating and consuming it. Therefore, leave this chapter with a few critical pieces of knowledge that will help you better grasp research. This paragraph might read cynically, but here is some food for thought.

- You can’t always trust research

- Different techniques can lead to more practical outcomes

- Sampling is intricate and involved

- Analyzing results takes some special care

- Conflicting outcomes can confound application

- It isn’t always worth conducting

One of the main difficulties with consumer research in sports is that stated and observed behavior can often be different. This distinction is always true, but it can be more accurate for sports. For instance, season-ticket-holders may respond poorly to a survey that might indicate price increases yet still renew at high rates. People try to game surveys hoping their responses can tilt Fortuna’s wheel 73 in their favor.

Additionally, research methods can be combined with more advanced discovery, like purchasing data from a data broker74 such as Acxiom. We’ve spoken about the problems with third-party data quite a bit. For example, research conducted by fellows at Deloitte found serious inaccuracies with data purchased from a well-known data broker (John Lucker and Bischof 2017).

“Our survey findings suggest that the data that brokers sell not only has serious accuracy problems but may be less current or complete than data buyers expect or need.

Accurate data is an enormous problem. Garbage-in, garbage-out. I’ve seen this in practice when conducting surveys by comparing stated responses to questions on gender, ethnicity, and age to data purchased on the market. So, whenever practical, “Trust, but verify.”

Despite the issues you will encounter, research should be a fundamental component of business strategy. The bigger the problem, the more critical conducting worthwhile research becomes. Understanding how to frame questions that some form of research can answer is an overlooked skill set. Getting good at it takes experience. Hopefully, this chapter will get you thinking about this at a high level and give you the rudiments of a toolbox you can use to be more effective and confident at conducting and analyzing research.

You will primarily conduct rather simplistic satisfaction surveys through email and deployed after games or periodically throughout the season. Conducting surveys follows a distinct process. We’ll loosely frame this chapter around a method for designing a survey borrowed from “Designing Surveys, a guide to decisions and procedures.” (Johnny Blair 2014) These steps include:

- Planning and survey design

- Questionnaire design and pretesting

- Final design and planning

- Sample selection and data collection

- data coding, analysis, and reporting

Since the most common research method you will likely employ will be the emailed survey, we will focus on this. This chapter will demonstrate the basics of survey design, data preparation, and analysis. We’ll also discuss our philosophies for creating them and applying the results. However, since we have already demonstrated some of the techniques we would use for analysis, we will focus most on planning and survey design.

9.1 Designing experiments and hypothesis testing

There are many ways to design an experiment, which is also an extremely deep subject. Additionally, trying to become an expert on clinical experiment design will give you a case of impostor syndrome. This stuff is full of confusing statistics jargon and combines multiple knowledge bases. Since putting together specific designs (a fractional factorial design) is relatively mechanical, you can follow a recipe and do it correctly. Ensuring the underlying assumptions regarding your analysis plan are fulfilled can be much more challenging. Luckily, you aren’t subject to some peer review mechanism by people who conduct research as a profession. We’ll hit the high points and demonstrate some practical examples. In terms of a framework for discussion, we used “Designing experiments and analyzing data” (Scott E. Maxwell 1990) by Maxwell and Delaney and “Applied Survey Data Analysis” (Steven G. Heeringa 2010) by Heeringa, West, and Berglund as a high-level reference.

Experiment design is really about validity. You are concerned about your results having merit in real-world applications. There are also multiple types of validity, such as statistical conclusion validity75 and construct validity76. Much of our analysis has been on statistical conclusion validity. Do your results meet specific criteria related to testing your hypothesis? Construct validity refers to drawing the correct conclusions from that analysis. There are many other potential problems with the validity of an experiment. Always keep this in the back of your mind.

You’ll also hear a lot of common terminologies when designing an experiment. The most common terms you will hear are likely calls for a Treatment and Control group. You need this basic structure for an A/B ^ [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A/B_testing] test. Understanding an A/B test sounds straightforward enough. One group receives a stimulus (perhaps a specific advertising mechanism), while another doesn’t. You use this fact to test whether the stimulus had a measurable impact on a particular outcome, such as purchase intent. The designs of these tests can be simple such as in the case of an A/B test, or very complex. Ultimately, you should subject the findings of your tested groups to some statistical tests. You are looking for some level of assuredness in answering the question as to whether there are valid differences between individuals in two or more populations. Afterward, you have to interpret everything correctly. With any luck, you can build some causal models using the results.

9.1.1 Hypothesis testing

Hypothesis testing needs to be clarified because of the sentence structure you will encounter. If you don’t have a statistics background, you must take the time to understand hypothesis testing. The next couple of paragraphs will touch on the high points. After that, there are a few steps and a few statistics that you will want to consider. You start by specifying an hypothesis. Let’s use an example.

I want to understand if season ticket holders spend more on concessions than non-season ticket holders. My Null hypothesis is that the mean spend of season ticket holders - the mean spend of non-season ticket holders = 0. If I reject the null hypothesis, it implies that the mean spend between these two populations is not equal to 0. Go ahead and reread that sentence. I know it doesn’t make any sense. Please don’t blame me. I didn’t create this stuff.

Let’s take a sample from both groups. We’ll create some fake data here for this exercise.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Create spend data

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

sth <- as.data.frame(matrix(nrow=1000,ncol = 2))

fan <- as.data.frame(matrix(nrow=1000,ncol = 2))

names(sth) <- c('spend','type')

names(fan) <- c('spend','type')

set.seed(715)

sth$spend <- rnorm(1000,25,7)

fan$spend <- rnorm(1000,18,7)

sth$type <- 'sth'

fan$type <- 'fan'

# Sample data

set.seed(354)

sth_samp <- sth[sample(nrow(sth), 400), ]

fan_samp <- fan[sample(nrow(fan), 400), ]| spend | type | |

|---|---|---|

| 278 | 16.34787 | sth |

| 699 | 23.83900 | sth |

| 581 | 16.23701 | sth |

| 611 | 32.08364 | sth |

| 943 | 36.39058 | sth |

| 761 | 39.41891 | sth |

We will use the sample to make an inference about the general population. There are four possible outcomes for a hypothesis test:

- The null hypothesis is false. You reject it. The means are not equal to zero, and season ticket holders spend differently than regular fans.

- The null hypothesis is true. You do not reject it. Season ticket holders spend less on average than regular fans.

- The null hypothesis is true, but you do not reject it. This is called a type I error.

- The null hypothesis is false, and you fail to reject it. This is called a type II error.

The primary way to test an hypothesis is by using a student’s t-test. So let’s apply it here and take a look at the output.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# T Test

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

t_test <- t.test(sth_samp$spend,fan_samp$spend)| t.test_results | |

|---|---|

| estimate | 6.560613 |

| estimate1 | 25.0236 |

| estimate2 | 18.46299 |

| statistic | 13.24688 |

| p.value | 2.573968e-36 |

| parameter | 789.8377 |

| conf.low | 5.588437 |

| conf.high | 7.532789 |

| method | Welch Two Sample t-test |

| alternative | two.sided |

In this case, we reject the null hypothesis that the differences in means are zero. The alternative hypothesis is true. There are also alternatives to the base t.test .You also need to consider if the sample sizes are equal and if other assumptions that you are making are accurate.

9.1.2 Sampling

Covering hypothesis testing leads us to another major consideration in experiment design. The validity of your experiment will depend heavily on your sampling methodology. What questions should you be asking about your sample? Many of these questions are related to how your sample could potentially bias your results:

- Is my sample representative of the population I am trying to test?

- Is the sample large enough to apply to the broader population?

- Does the sample need to be random?

As you can imagine, this could get complex.

From the preceding example, how do we know how many people to sample? We can use a power analysis77 to give us an idea. We’ll evaluate our data using the pwr (Champely 2020) package. The following example is adapted from Kabacoff (Kabacoff 2011).

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Power analysis

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

effect_size <- 3/sd(sth_samp$spend)

signif_lvl <- .05

certainty <- .9

pwr_test <- pwr::pwr.t.test(d = effect_size,

sig.level = signif_lvl,

power = certainty,

type = 'two.sample')The results of this test are in table 9.3.

| pwr_t_test_results | |

|---|---|

| n | 127.1571 |

| sig.level | 0.0500 |

| power | 0.9000 |

According to our test, we need 127 participants in each group to calculate an effect size of .4 with 90% certainty with no more than a five percent chance of concluding that there is a difference when there isn’t. So again, reread that sentence.

This example of a power test could be more complex. There are several potential issues, such as the underlying normality of the data, whether the values are independent, if the samples are correlated, and many more. We aren’t going to go through this in any more detail. However, you must understand that getting a good sample takes some rigor. Use a reference and follow a process. You’ll be able to explain yourself later (You might just be explaining yourself to yourself).

9.1.3 Experimental design

One common experiment design is called a factorial design. 78. Factorial designs are common and, similarly to everything else, can spiral into complexity. The goal is to ensure you test each possible combination of factors against each test subject. A full factorial design is only sometimes feasible because it has cost trade-offs. It may not be possible to deploy as many surveys as you would like. In this case, a fractional factorial design may be used. 79 This section will cover a simplified example. You would only use something like this in sports if you were designing a conjoint or formal experiment. There are also many other designs, such as a combinatorial design80. If you are interested in them, you must research these methods independently. I want you to be aware of them. If nothing else, you can impress a third-party researcher that you will likely encounter.

Let’s take a look at a basic factorial design for an experiment. We will use the AlgDesign (Wheeler 2022) library to build our design. Let’s assume we have two sections we want to look at Dugout Seats and Homeplate seats. We want to understand consumer preferences based on each section’s high, low, and medium prices. Let’s say that we had three possible prices.

| Price Level | Dugout | Home Plate |

|---|---|---|

| High | 95 | 95 |

| Medium | 85 | 85 |

| Low | 75 | 75 |

| … | … | … |

Use the gen.factorial function to produce a factorial design based on the preceding options.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Factorial Design

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

library(AlgDesign)

fd <- gen.factorial(levels = 3,

nVars = 2,

center = TRUE,

factors = FALSE,

varNames = c("Dugout Seats",

"Homeplate Seats"))

#> Warning in xtfrm.data.frame(x): cannot xtfrm data frames| Dugout Seats | Homeplate Seats |

|---|---|

| -1 | -1 |

| 0 | -1 |

| 1 | -1 |

| -1 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 |

| -1 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 |

In this case, we have nine different combinations that we will need to put in front of our survey recipients. The numbers represent which factor is to be tested. The first three rows indicate that the high, medium, and low prices for dugout seats are to be tested against the low price for home plate seats:

| Price Level | Dugout | Home Plate |

|---|---|---|

| High | 75 | 85 |

| Medium | 85 | 85 |

| Low | 95 | 85 |

| … | … | … |

The survey would give the respondent the option to purchase either seat at each level:

Which seat would you prefer at the indicated prices?

In this case, we would show a picture of the view from the seats. We are testing how fans value the view from these seats relative to one another. There may also be mixed effects81 here. You have to be careful with these sorts of experiments. How would you analyze the results? There are a few ways. Let’s create some data to see what we would do.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Survey Responses

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

survey_responses <-

tibble::tibble(dugout = factor(unlist(rep(fd[1],1000))),

homePlate = factor(unlist(rep(fd[2],1000))),

selection = NA)

survey_responses$dugout <- sapply(survey_responses$dugout,

function(x) switch(x,'-1' = '75',

'0' = '85',

'1' = '95'))

survey_responses$homePlate <- sapply(survey_responses$homePlate,

function(x) switch(x,'-1' = '75',

'0' = '85',

'1' = '95'))

survey_responses$respondent <- c(rep('sth',4500), rep('sin',4500))

selection <- list()

x <- 1

set.seed(755)

while(x <= nrow(survey_responses)){

s1 <- survey_responses[x,1]

s2 <- survey_responses[x,2]

selection_list <- c(s1,s2)

selection[x] <- sample(selection_list,

size = 1,

prob = c(.2,.8))

x <- x + 1

}

survey_responses$selection <- unlist(selection)

survey_responses$section <-

ifelse(survey_responses$selection == survey_responses$dugout,

'dugout',

'homePlate')Our survey responses look like this:

| dugout | homePlate | selection | respondent | section |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 75 | 75 | 75 | sth | dugout |

| 85 | 75 | 85 | sth | dugout |

| 95 | 75 | 95 | sth | dugout |

| 75 | 85 | 75 | sth | dugout |

| 85 | 85 | 85 | sth | dugout |

| 95 | 85 | 95 | sth | dugout |

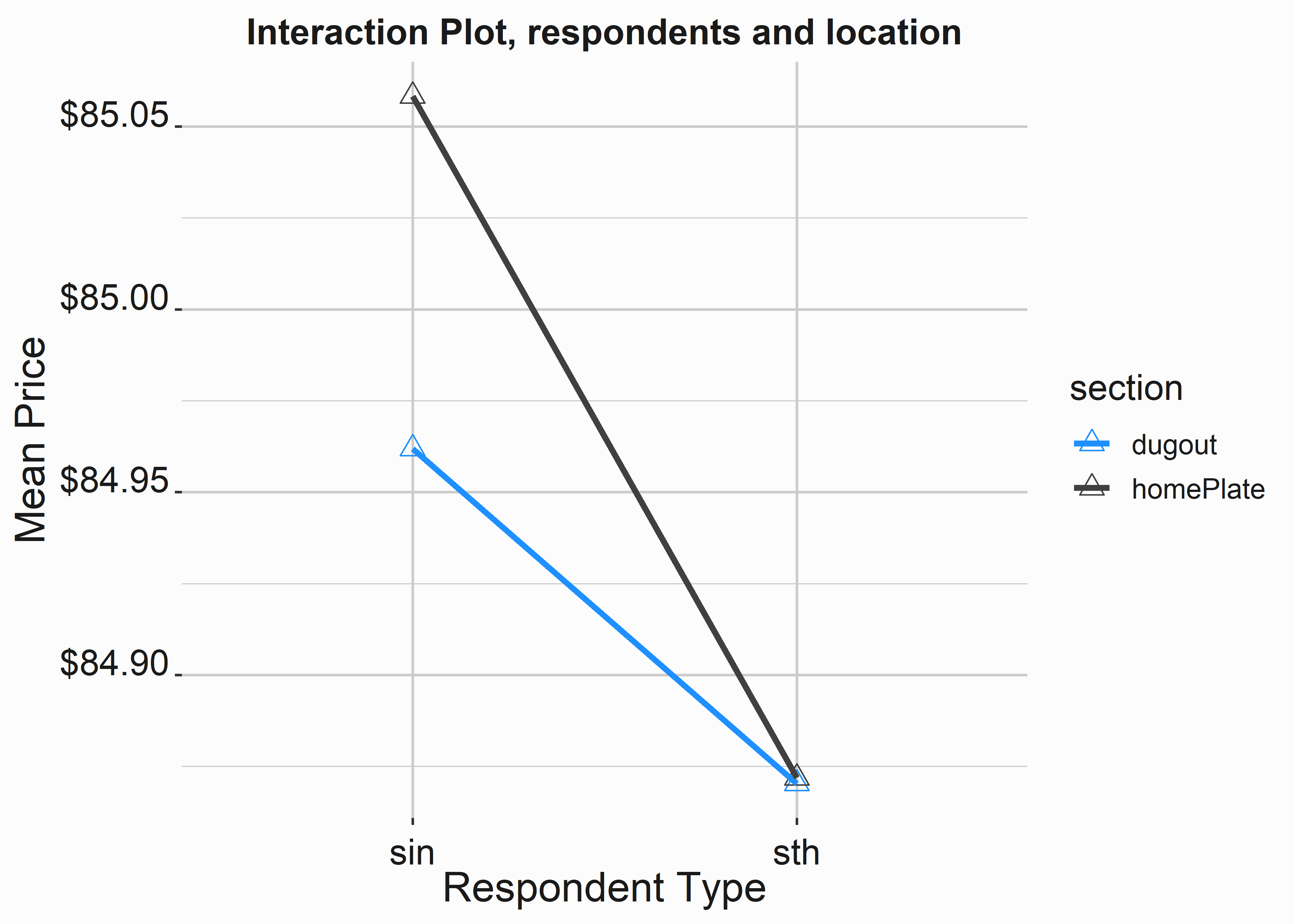

We can create an interaction plot with the following code.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Interaction Plot

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

ip_data <- survey_responses %>%

group_by(respondent,section) %>%

summarise(meanSelection = mean(as.numeric(selection)))

g_xlab <- 'Respondent Type'

g_ylab <- 'Mean Price'

g_title <- 'Interaction Plot, respondents and location'

ip_plot <-

ggplot(ip_data, aes(x = respondent,

y = meanSelection,

color = section,

group = section)) +

geom_point(shape=2, size=3) +

geom_line(size = 1.1) +

scale_y_continuous(label = scales::dollar) +

scale_color_manual(values = palette) +

xlab(g_xlab) +

ylab(g_ylab) +

ggtitle(g_title) +

graphics_theme_1

Figure 9.1: Interaction plot of survey results

This plot suggests that the effect of the view based on seating location is inconsistent between single-game ticket buyers and season ticket holders. While season ticket holders value the views as equivalent, single-game buyers may be willing to pay more for home plate seats when given a choice between home plate and dugout seats. You can see how complex these designs can become. This simple example gives you the basics of designing an experiment and producing a basic analysis.

9.2 Planning and design

Since we covered segmentation in chapter 4, we’ll base our example around gathering information about building some psychographic segments. This is a helpful example because you could do one of many things. There are opportunities to:

- Hypothesis test. For instance, do specific segments tend to spend more than others?

- Look for causal links between attitudinal data and long-term purchase behavior.

- Discover groups within our population that follow specific behavioral patterns.

- To look for correlations between behavior and specific activities.

The best way to illustrate this process is by creating a specific scenario.

The Nashville Game Hens’ marketing department is interested in approaching marketing efforts more sophisticatedly. We want to understand a couple of different things about our fanbase:

- To understand our market structure. Who is coming to games, and how does this compare to the region’s general population? Then, we want to break that market structure into logical segments that can be discovered through multiple channels to use in marketing campaigns.

- To understand something about our brand affinity and what it means. How is our brand perceived in the market?

These are two very broad problem statements. These topics might cover multiple facets, such as price sensitivity, media consumption, general interests, or financial status. We can also see that question two won’t allow us to use any internal data. We are forced to collect it. We’ll need to carefully structure a plan to ensure we answer the questions we are asking. These two statements didn’t ask the questions we needed at all. We are going to have to interpret them for our internal client contextually.

We need to structure how we plan on attacking this effort so that we can address the request. What are we concerned with? Let’s interpret the questions:

Question one is concerned with a generalization of a fan. We need to create a specific number of groups of people that are more alike to each other than to other groups and compare them to a broader population sample that includes our fan base and the regional or national population. I can already tell you that this will be difficult. If you have one hundred thousand people in a sample, you have one-hundred-thousand segments. Attempting to generalize them into an arbitrary number of boxes that can be well understood will be difficult.

Question two is concerned with how an individual feels about our brand. Our competitive set may need to be uncovered. Are there other sports teams in our region that we could measure ourselves against to evaluate our brand? Is there a broader competitive set we should consider? How does our in-park experience impact our brand? This survey isn’t a run-of-the-mill satisfaction survey. This one is going to require some work.

Another main concern in this example that influences our decision-making process is the tension between discoverability, accuracy, and utility. Will this analysis be used to target specific individuals? Is the study something that we can cast on broader segments of people to understand where they fit in our segmentation scheme? How accurate will the results be? If they aren’t very accurate, the utility of what promises to be an expensive project may be significantly reduced. Make sure everyone clearly understands expectations and trade-offs.

9.2.1 Understanding the makeup of a club’s fans

From a brand perspective, sports is unique. You don’t typically see someone walking around a city with a hat advertising their favorite shampoo. Sports crosses a vast swath of individuals and has major cyclical components. Endemic concerns might include the following:

- Several ticket classes with relatively small populations have an out-sized revenue contribution

- Responses may be different during the season or at different times during the season

- There are multiple levels and forms of consumption

Referencing the first point, corporations may make up a large portion of season tickets. Is demographic information of any use here? Is there a distinction between someone who purchases tickets for their business and a fan who purchases to enjoy the game? What does enjoying the game mean? Individuals may consume through any number of formats and channels controlled by the club or not regulated by the club. Many implicit and explicit signals imply fandom. Are we mainly concerned about ticket sales for this segmentation project?

In our case, we will be concerned with ticket sales. We have seen some of these techniques. The factor analysis we conducted in section 5.4 is an example of a potentially helpful approach. The data here would have come from a survey asking why someone attends a game and what they do when they attend a game. The point is that we had a plan for the data we collected. We knew we would use factor analysis to derive insight from the survey, and we designed the study to accommodate that technique.

Ticket sales are typically public information, with teams tending to announce sales figures82. So let’s take a moment to analyze some data from MLB in 2019.

| Club | Sales |

|---|---|

| Dodgers | 3,974,309 |

| Cardinals | 3,480,393 |

| Yankees | 3,304,404 |

| … | … |

These teams all had a high number of ticket sales. How many individuals does this represent? We have to make some assumptions.

- Average of 20,000 FSEs in season tickets

- Season ticket holders buy an average of 4 tickets

- Single-game buyers come to an average of 1.5 games and buy three tickets per game

- Groups of larger than 20 make up 10% of sales

We would have to make many more assumptions, but the point is clear. If we look at purchasers instead of people who attended games, the results may look different. Additionally, we aren’t considering fans who only watch on TV or follow through other media. What about default fans? Fans that identify with the team but don’t exhibit explicit signals that they are a fan. What about people that purchase merchandise but don’t consume the primary product? Market structure is complex in this industry.

The question remains. How large is our actual market, and who precisely are we attempting to segment? The answer to this question might be the dreaded “Yes.” The honest answer, like everything in analytics, is that it depends. The project forks in different directions depending on the answer. Let’s refer back to our question. We have two objectives:

- To understand our market structure. Who is coming to games, and how does this compare to the region’s general population?

- To understand how our brand is perceived and interpret this perception in a way that is useful for making decisions.

How might we obtain the information in question 1? Part of this data probably already exists.

- Is there governmental data that we access, like census data?

- Observational research

- Emailed surveys

- Third-party research

Observational research could be as simple as walking onto the concourse during the game and writing down what you see. Technologies could also be deployed here. For example, facial recognition technologies 83 can even automate this procedure to a large extent.

How would we get the information in number 2? Number two also looks like a combination of techniques:

- Emailed surveys

- Third-party data

What features are we interested in looking at? At this stage, we won’t know what could matter. For instance, if you are looking for people that might purchase season tickets, wealth factors like household income might be necessary. At a minimum, you’ll want basic demographic features such as:

- Age

- Number of children

- Marriage status

- Gender

- Ethnicity

Why do you want a feature such as ethnicity? Why does it matter what ethnic group an individual belongs to? If an ethnicity behaves differently from another, it could be helpful to your advertising department in terms of channel or the location of particular OOH efforts. Additionally, the data could be used longitudinally for a variety of purposes.

Look carefully at the potential questionnaire and data quality issues. Carefully considering the question is the best way to fix problems that may manifest later. The more time you spend considering the question, the better your final results will be.

9.2.2 Selecting the correct research method

A sports team may have several needs from a consumer or brand-equity perspective. However, sports fandom can be a fickle thing. As we have discussed, fandom exists for many reasons. Switching teams is more challenging than switching to a different hair treatment. Fans tend to be sticky, which is one of the main reasons research often takes a back seat in the decision-making process. However, sports clubs face headwinds along several consumer behavior dimensions, such as brand loyalty and media consumption (Jeff Fromm 2018). Properly developed and deployed research is the only method we have to confront these issues in an informed way. In sports, we have slightly different needs for research relative to other industries because of our unique brand positioning with our fans and the fashionability that ebbs and flows along with team fortunes. These questions might include:

- What is our competitive set?

- What do consumers like about the product?

- What are our consumer’s constraints (financial, monetary)?

- What are our fan’s awareness levels with sponsors?

- What do fans think about our prices?

- How are we perceived in the market relative to other properties?

- Should we introduce a loyalty program?

Different needs have different requirements in terms of research. Multiple types of surveys are designed for specific tasks. These specialty surveys must be designed in a particular way and require some knowledge to interpret. Examples include:

While there is significant variation within techniques, relatively few methods are commonly deployed. Different designs also have strengths and weaknesses. For example, a Van Westendorp survey may demonstrate how prices for certain products (like a seating section) are perceived, but it doesn’t inform us on willingness-to-pay (covered in chapter 6. A conjoint experiment might give you a better indication of willingness to pay. You could also design formal field experiments to accomplish the same thing.

Other studies require longer time horizons. Longitudinal studies measure the change in perception over time. Like other topics we have covered, focused research looking to uncover causal links between activity and outcome is the goal. Each stage has several substages that need to be thought through. The planning process is critical.

9.2.3 Building and designing the questionnaire

We’ve seen that building surveys can be extremely complex if you are trying to build a durable study. In this section, we’ll focus on building the questionnaire. Coding survey questionnaires is painful work. I try to follow the following principles:

- Plan how you will use and analyze the data.

- Don’t ask a question if you will not use it.

- Don’t survey too much or too often.

- Pay attention to the survey burden in terms of length

Some surveys may be very focused and look to uncover just one or a few pieces of insight. Other surveys may be extensive and more exploratory. (Johnny Blair 2014) Many research tools can help you design effective surveys. For example, products such as Qualtrics88 or Survey Monkey89 will automatically analyze your survey regarding burden. They also contain banks of questions that you can use as a resource.

Often you’ll break a more extensive survey into specific sections:

- Demographics

- Brand

- Satisfaction

- Product

As a rule, try to keep surveys as short and relevant as possible. Think carefully about sequencing. For instance, what is the most important thing you need to know? Put those questions in the front, followed by any qualifying information.

9.2.4 Qualifying your sample

It is often critical to qualify your sample. Qualifying your sample will make the results more relevant. It may reduce the costs 90 of deploying the study. These questions may be behavioral or demographic. This section might ask questions such as:

- What is your gender?

- Male

- Female

This is important because you might have a quota. For example, a sample that is 85% male may not be desirable. There are also guides about asking questions that are increasingly controversial. Inclusivity is also something to consider. You can find any number of guides on writing inclusive surveys91. Be consistent. Additionally, you might have quota limits on specific ethnicities.

- What is your ethnicity?

- White or Caucasian

- Black or African American

- Eastern Indian

- Asian

- Native American or Pacific Islander

- Latinx

Did we denote these ethnicities correctly? It’s essential to consider how different nomenclatures go in and out of fashion. For example, Latinx has begun to replace “Hispanic or Latino.” I am not here to judge the merits of replacing these terms. Just be aware that everyone will have an opinion here. Build yourself a backstop of awareness. Hispanic is also a problematic concept. What makes someone Hispanic? Are they also black or white? Is this important? You’ll have to make judgment calls based on what you are trying to achieve with your survey.

Some people may even poison your sample. For example, many surveys qualify respondents with a question such as:

- Do you are anyone in your family work in marketing research?

If someone works in marketing research, they may understand some of the mechanisms you are trying to deploy. This knowledge could bias the results of certain types of questions, such as conjoint analysis.

In sports, asking about fan avidity is widespread:

- Are you a fan of the Nashville Game Hens?

However, asking about specific avidity in the screening section is often unwise. Instead, a better method might be to ask a question like this:

- Please rate the following activities in terms of your interest:

| Activity | Interested | Not Interested |

|---|---|---|

| Knitting class | ||

| Attending an MLB game | ||

| Attending a concert | ||

| … | … | … |

If this survey is distributed through a third party, you won’t be giving away the fact that the study is about the Game Hens. It also allows you to disqualify anyone not interested in attending a game. It all depends on what you are trying to accomplish.

In addition to screening questions, dummy questions are typically added to a survey to guard against indifferent respondents. For instance, you might embed a question like this into your survey:

- Please select the fourth answer to this question:

- Answer 1

- Answer 2

- Answer 3

- Answer 4

You will be surprised at how many people will get this question wrong. It is best to disqualify all responses from someone who gets this question incorrect.

9.2.5 Typical survey questions

There are specific questions that are often asked on surveys. I include a demographic section here because it is usually interesting and commonly included on questionnaires. In addition, there are preferred ways to broach this subject, and it is essential to discuss them specifically.

If you can track respondents, you may already have their demographic information. If your survey doesn’t require an answer to a question, it is essential to consider where this information is sequenced on the survey. A good practice is to ask the respondent if they would like to answer some demographic questions:

Would you like to answer a few demographic questions?

Asking this question will prevent people from ignoring the rest of the survey if they aren’t interested in answering demographic questions. Consider putting demographic questions at the end of the survey. Placing these questions at the end of the survey will ensure you collect other information you deem more important. Additionally, consider if you are using this data longitudinally. Changing the format of these questions may make analysis difficult if you compare the data to older data sets.

Let’s walk through some typical examples of demographic questions. This seems a little pedantic, but how you ask these questions is important.

Instead of asking for an age, I prefer to ask for birth year and then calculate the age:

- What is the year of your birth?

Obtaining the birth year will make it easier to compare this data to data collected in the past or the future. It also makes it easy to place people into demographic buckets. Additionally, you’ll be able to build more accurate scatter plots of the data. When I can, I collect numerical data. While age can be a sensitive subject, I haven’t seen a problem with simply asking for a birth year.

Asking about educational achievement is also common. Why do we care? Education is often a proxy for wealth. Someone may not be comfortable telling you their income, but education isn’t as taboo.

- What is the highest level of education that you have completed?

- High school

- Some college

- College

- Graduate degree

Marital status is also commonly asked. You’ll want to include an other category here. You will typically see many different arrangements, such as separated, divorced, or widowed. I don’t typically include them. If you are asking about something to do with sports, what will you do with this? Sports may salve loneliness, but how will you find all the widowers? I don’t see a lot of practical application here in our context. Keep it simple and omit it if you can’t think of a possible use outside of exploratory analysis. Some answers might be simple proxies for asking about things such as sexuality.

- What is your Marital Status?

- Single

- Married

- Partnership

- Other

Asking about children is also typical. Some sports are seen as family activities more than others. Additionally, stoking interest in young people is a longer-term strategic play. How much effort do merchandisers put into appealing to young people with sports?

- Are there any children under the age of 18 living in your household?

- Yes

- No

Almost all sports look to develop youth, and understanding how many children attend games is essential. Knowing the age of children is also important. There is a big difference between a five and a 16-year-old. If the respondent answers ‘yes’ to the preceding question, you would typically present them with something like the following question:

3.a. Please select their age(s). - 0 to 2 - 3 to 5 - 6 to 10 - 11 to 15 - 16 to 17

In this case, we are using a multi-select. Multi-select is more challenging to work with on the back end and will require additional data wrangling. The more complicated the question structure, the less likely you will use it. You have to strike a balance between the ideal and the practical.

Geography is especially important for a club. Season ticket holders likely live in a relatively small area that surrounds the stadium or ballpark. Idiosyncrasies in a market also make understanding the relative geography critical. For example, the lack of rail or other infrastructure may make the stadium less accessible from certain parts of the region. The most generalized way to get geography is by asking for a zip code.

- Please enter your zip code:

You may not need this data point if you have ticketing or shipping info. It is best to get an actual address to collect the latitude and longitude, but zip code is the next best readily available piece of information.

Income is tricky. If the survey isn’t anonymous, many people may choose not to answer this question or deceptively answer it. I’ll include the net present value of my company’s life insurance in the figure. We could all use more money. Additionally, this question would be more interesting if it was continuous. We can force it to be later if we would like. One of the big decisions here is how granular to make the question.

- What is your annual household income?

- Under $10,000

- $10,000 - $49,999

- $50,000 - $99,999

- $100,000 - $149,999

- $150,000 - $199,999

- $200,000 - $249,999

- More than $250,000

This data is ordinal, meaning we want it displayed in a specific and logical order. Often questions and answers are randomly reshuffled. Reordering questions and answers is done to protect against bias introduced by someone habitually answering questions similarly. Some answers will need to be randomized, but if the question is long, it might make sense to alphabetize the answers. Let’s look at an example:

- Which answer best describes your occupation?

- Administration/Managerial

- Agriculture

- Clerical/White Collar

- Craftsman/Blue Collar

- Educator

- Financial

- Homemaker

- Legal

- Medical

- Professional/Technical

- Retired

- Sales/Service

- Self Employed

- Student

- Other

Are these occupations logically organized? Is Agriculture an occupation or an industry? Do you care if someone is in the military or works as a youth pastor at a church? This is more of a color question. Consider omitting it if you don’t have a specific use. Other is likely to attract a large number of responses. For example, if someone is an accountant, do they consider themselves Clerical or Finance? I don’t typically like this question.

Many other demographic questions could be conceived, but the preceding examples cover the basics you will likely deploy. But, again, pay attention to how the answers are displayed and the data type. This stuff always requires some specific care.

9.2.5.1 Avidity questions

Understanding avidity is also crucial in sports. Unfortunately, this also tends to be misunderstood. How can you measure someone’s enthusiasm for sports? Several explicit and implicit signals might demonstrate avidity. Which individual in the following example is the most avid fan?

- A person purchases season tickets for $700

- A person purchases season tickets for $20,000

- A person purchases single game tickets for $1,500

These explicit signals likely demonstrate some level of affinity, if not avidity. There are also interactions at play. Are we just measuring wealth? Be cautious with avidity. If you organize spend into leveled buckets, you aren’t measuring avidity.

Implicit signals are more subtle.

- A person purchases merchandise online

- A person visits the website often

- A person enrolls their child in a free kid’s club membership

The person might have purchased items for a gift. We don’t know. You might also ask a person specific questions. A common one might be:

- How big of a fan are you?

- I love the Game Hens. I live and die for them.

- I really like the Game Hens. They are one of my favorite teams.

- I identify with the Game Hens, but am a casual fan.

- I don’t really care about the Game Hens. I am not a fan.

- I hate the Hens. I hope they lose every game.

I think of this sort of question on a Likert scale. Something like 1-5 or 1-7. This is a typically used convention; you can think of what lies underneath these questions similarly. For example, “I love the Game Hens. I live and die for them.” represents a five. You can see how it is not easy to word these questions. Pay attention here. You can easily write a question that is ambiguous or difficult to understand.

Additionally, should you include an odd or even number of answers? An even number of responses forces someone to pick one side. Forcing respondents onto one side of the fence could be helpful.

9.3 Brand affinity

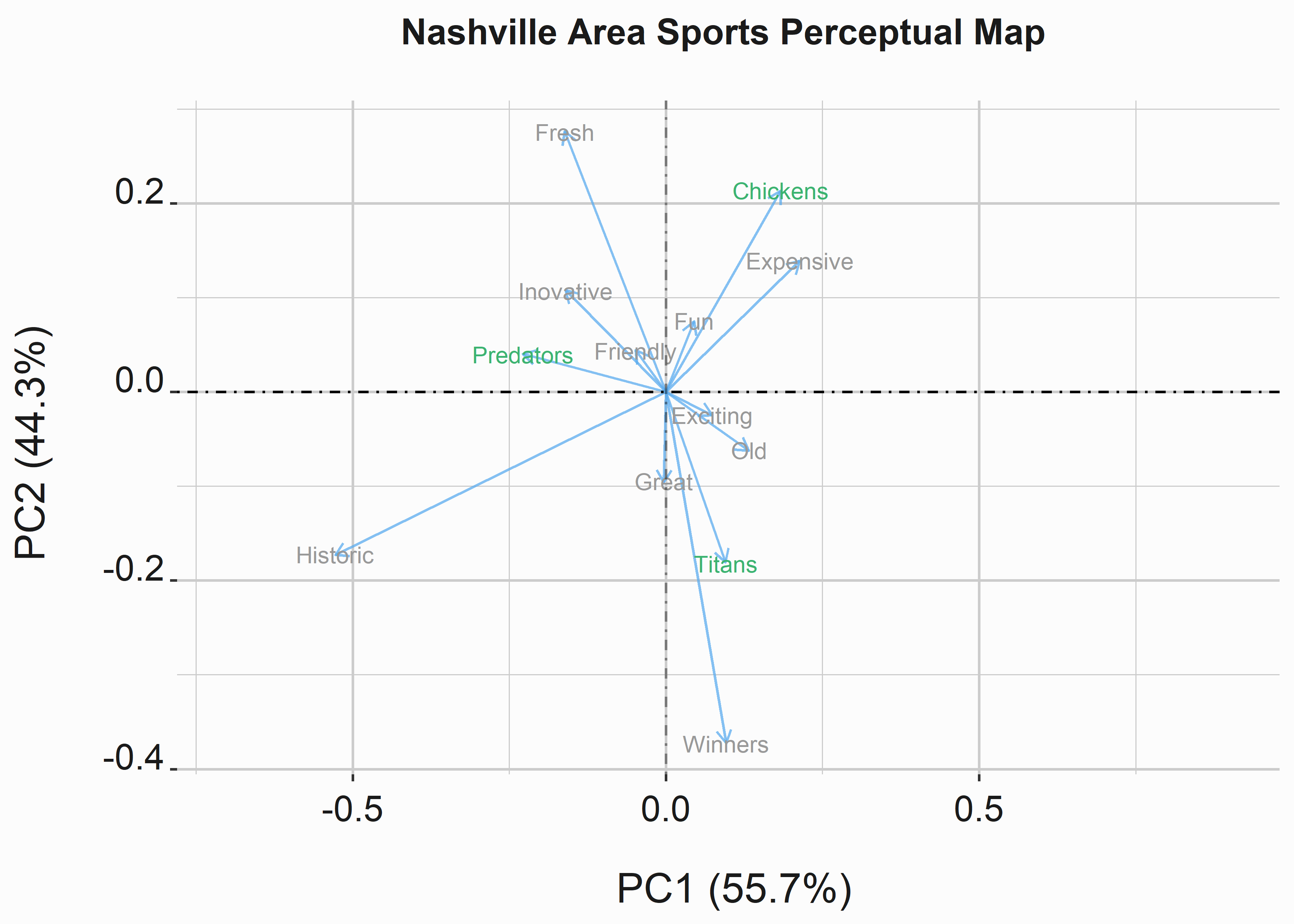

Gauging brand avidity is difficult. We’ll explore a tool to look at one brand avidity component called a perceptual map. We’ll use the library anacor (Mair and De Leeuw 2022) to accomplish a part of this task. This package is built to assist with correspondence analysis92. Do a little research on this topic.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Calculating scores for perceptual data

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

library(anacor)

pd <- as.data.frame(FOSBAAS::perceptual_data)

row.names(pd) <- c('Chickens','Titans','Predators')

anHolder <- anacor(pd,ndim=2)

anHolderGG <-

data.frame(dim1 = c(anHolder$col.scores[,1],

anHolder$row.scores[,1]),

dim2 = c(anHolder$col.scores[,2],

anHolder$row.scores[,2]),

type = c(rep(1,length(anHolder$col.scores[,1])),

rep(2,length(anHolder$row.scores[,1]))))This function used the aggregated perceptual data that we created in chapter two. The question read like this:

How do you feel about the following sports properties? Please check all that apply for each of the teams listed.

This initial data set took the form of a multi-select table:

| Team | Friendly | Exciting | Winners | Losers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Came Hens | ||||

| Predators | ||||

| Grizzlies |

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Create a perceptual map

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

library(scales)

library(RColorBrewer)

library(grid)

library(gridExtra)

basePal <- c('grey60','mediumseagreen','grey40','steelblue1')

g_xlab <- '\n PC1 (55.7%)'

g_ylab <- 'PC2 (44.3%) \n'

g_title <- 'Nashville Area Sports Perceptual Map \n'

PM <-

ggplot(data = anHolderGG,aes(x=dim1,y=dim2,

colour=factor(type))) +

geom_point(size = .5, fill = 'white', colour = 'White') +

geom_segment(data = anHolderGG, aes(x = 0, y = 0,

xend = dim1,

yend = dim2),

arrow = arrow(length=unit(0.2,"cm")),

alpha = 0.75, color = "steelblue2") +

geom_text(aes(label = rownames(anHolderGG)),

size = 3.2,

position = "jitter") +

scale_color_manual(values = basePal,

name = 'Perception',

breaks = c(1,2),

guide = FALSE) +

xlab(g_xlab) +

ylab(g_ylab) +

ggtitle(g_title) +

graphics_theme_1 +

geom_vline(xintercept = 0,lty=4,alpha = .4) +

geom_hline(yintercept = 0,lty=4,alpha = .4) +

coord_cartesian(xlim = c(-.7,.9)) This code produces the map in figure 9.2

Figure 9.2: Perceptual map of Nashville Sports Properties

How do we read a perceptual map? In this case, the Chickens tend to be seen as Fun and Expensive relative to the other properties. What does this mean? Perhaps we want to be seen as innovative. Being seen as innovative in our market may make us more attractive to specific sponsors. Whatever our motivation, a perceptual map allows you to visualize feelings around your brand relative to other brands. You can use it over time to take measurements around these feelings relative to initiatives that you hope will alter perception in your favor.

9.4 Other topics

We only covered a little in this chapter out of necessity. There is too much material. We covered some high points and discussed fundamental research components such as hypothesis testing and sampling. We also covered basic survey design and a couple of examples of survey analysis. We didn’t talk about causal models, but we have examples of this research throughout the book. It is often helpful to think about survey design through the lens of answering a specific question with a causal model. The main subjects that we didn’t cover that you should be aware of include the following:

- Social listening

- Brand personality studies

- Models based on acquisition

- Product recommendation

- Developing and positioning products

- Intercept surveys

- In-depth interviews

- focus groups

- Competitive intelligence

- Incentivization

The most obvious subject we should have covered is social listening, but we will cover it briefly here. Social listening has become a large industry, and dozens of platforms can aid you. While monitoring and responding to social content is essential, sentiment analysis is of little practical value. Additionally, word clouds and other typical consumption techniques for social are exciting but could be more surprising and informative. Feel free to disagree with me here. This sentiment comes from practice.

I find social listening value through the lens of media equivalency. Your sponsorship and social team needs to understand how much content is being placed through social channels and how to value that content. There are multiple ways to do this, but you will likely need the help of a platform for this task. Like any other media content evaluation, you’ll need to take volume, quality, and arbitrary value to estimate how much you return to sponsors.

We are only going to give a nod to focus groups. Where are focus groups interesting in sports? They serve a role in public relations in terms of season ticket holders. This is especially true outside the traditional focus group looking at customer preferences or constraints. Fan councils have become important, but care must be taken to ensure these groups remain on task. They can tend to degrade into complaint centers.

We aren’t going to mention the other topics at all. If you want to learn about them, there are resources available everywhere. Hundreds of agencies would gladly work with you. Sports teams are attractive marketing platforms, and working with them is prestigious. Take advantage of that prestige. The trick is to know what quality research entails and find a partner that also understands it. Finding competent help is a more difficult task than you think. You’ve been warned.

9.5 Key concepts and chapter summary

Research should be a foundation of strategic initiatives. Whether you are improving an operations process, pricing tickets, or building pitch decks for a sponsorship team, producing credible research is critical. We covered five main topics in this chapter:

- Planning and survey design

- Questionnaire design and pretesting

- Final design and planning

- Sample selection and data collection

- data coding, analysis, and reporting

Research is an enormous topic, but by focusing on a few widely used practices, you can develop sound strategies for leveraging and creating your research. We covered several important concepts and linked these activities to chapter 5 and chapter 6.

We also covered sampling, typical question styles, data types, and two specific examples covering brand affinity and conjoint experiments. Keep a few principles in mind as you deploy surveys:

- You can’t always trust it

- Different techniques can lead to more practical outcomes

- Sampling is difficult

- Analyzing results takes some special care

- Conflicting outcomes can confound application

- It isn’t always worth conducting