8 Promotions

It can be challenging to measure the efficacy of promotions. It becomes even more difficult if we take a more expansive view of promotions and consider all advertising as some form of promotion. Some clubs have begun to eliminate many forms of promotion if they cannot measure the outcomes. While this makes sense on some level, I don’t go that far. Major Sports brands are unique in some ways because they tend to carry themselves when the team performs well. However, you can’t always be good. So how do you reconcile these issues from the standpoint of promotions? This chapter will give a specific example of measuring the impact of a promotion and cover some of the nuances of this subject.

Why do teams have promotions? Like all marketing techniques, promotions exist to increase sales. In sports, they are typically a response to less anticipated demand than capacity. However, this concept can be paradoxical. Promotions perform best when the team is performing well on the field. If you were to take a multi-year point-of-view on marketing, you would likely make different decisions than if you only look at it from a fiscal-year standpoint. There are also brand considerations.

Additionally, there are competing philosophies on the use of promotions. A franchise can pull only so many levers to increase the likelihood of someone purchasing a ticketing product, and the biggest one is price. It is also important to note that they typically have a cost 71, so justifying a return on the investment is generally considered an essential part of the process (assuming your goal isn’t solely on maximizing revenue).

Typical sales promotions focus on value: getting more products for less money. However, you see a myriad of promotions in sports:

- Giveaways such as bobbleheads and hats

- Post-game concerts

- Buy one ticket, get one free

- Loyalty programs for season ticket holders

- Flash sales and other dynamic pricing promotions

Additionally, promotions may also have negative impacts on your brand integrity. For example, constantly reverting to price promotions can cause damage (Keller 2003).

“The objective of value pricing is to uncover the right blend of product quality, product cost, and product prices that fully satisfies the needs and wants of consumers and the profit targets of the firm.”

Furthermore, many channels are notoriously difficult to evaluate. Advertisements and promotions could occur in any number of places:

- OOH (out of home) refers to billboards, etc.

- Radio

- Television

- SEM (Search engine)

- Online agencies (Double-Click)

- Social Media

- Earned media, such as television coverage

- Podcasts

- Foundation activities and other charitable ventures

Social platforms have become an increasingly important part of advertisement. However, the platforms are walled gardens with proprietary algorithms for demonstrating ROAS. They don’t have the incentive to tell you something isn’t working. SEM is an even bigger problem and can be confounding. If I know, when you type “Game Hen Tickets” into google, it seems like it would be pretty easy to serve you an ad that can be tracked to a sale. SEM is more of a beachhead for secondary market sellers. The secondary markets, such as StubHub, tend to worry more about the volume of transactions. Since they operate across the spectrum of tickets, they are impossible to outspend.

Media evaluation is handled in specific ways. For example, A. I.-based methods using neural networks to measure exposure have become popular over the past several years. However, media equivalency is tough to estimate accurately and is typically propped up by some arbitrary figure. We’ll discuss evaluating advertising later in this chapter.

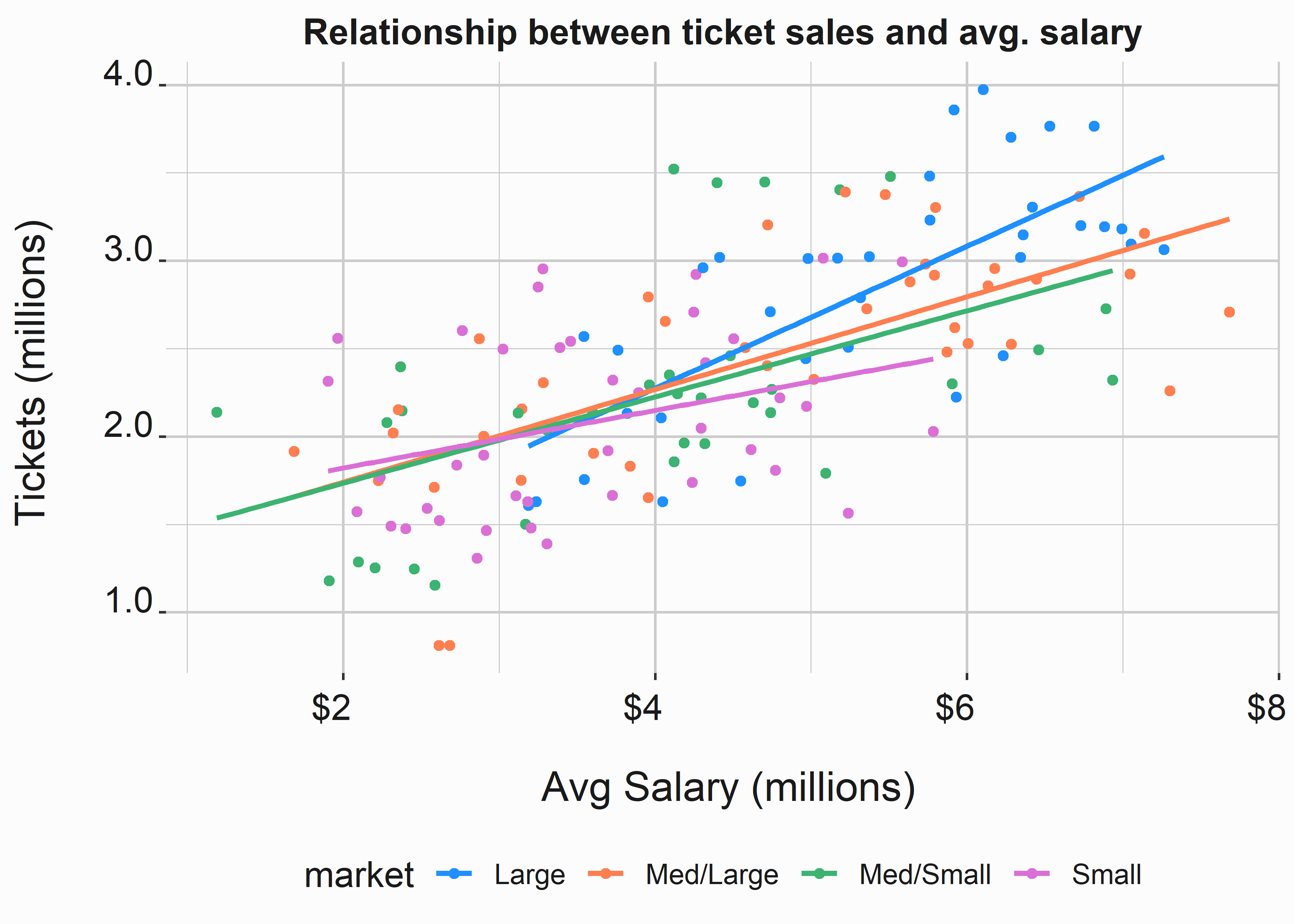

How do you know if any of your other marketing activity is worthwhile? In many cases, you don’t. Baselining sales can be complex because these activities are naturally baked into your sales. Some effects, such as what we see with salary in figure 8.1, are clearly outside a marketer’s influence.

The following graph was produced from public data on ticket sales and the average salary for MLB teams. The points are colored based on the population of the region.

Figure 8.1: Relationship between ticket sales and salary

There is some level of correlation between payroll and tickets sold. However, it isn’t clear that the size of the market impacts salary or sales. However, small markets tend to cluster near the bottom of the salary range, and large markets cluster near the top. We could use a clustering algorithm on this data to see if that is true, but this is only for illustration. It also begs the question.

If you can reasonably estimate ticket sales using macro factors such as payroll and wins, what impact do your marketing efforts have?

This capability is a sticky point, but it is valid. You will never find a president or owner that liquidates their marketing department. Indeed they do a lot more than push tickets. The most crucial factor for many clubs is likely the investment in the team. This reliance on team payroll is more acute for baseball because of the number of games. You are more exposed to perturbations in performance when you have more events. This is where the NFL has a significant advantage in parity (along with structural components related to salary floors and caps).

There is also a lot of complexity in specific market conditions. Therefore, there are several questions that we can ask ourselves when focusing on ticket sales.

- How many single-game tickets were sold to individuals outside our database?

- Do we recycle the same fans for promotions?

- Are average ticket sales higher during a major promotion?

- Is the turnstile higher during major promotions? How are F&B sales impacted?

- Can we identify a causal link between sales/turnstile/revenue during major promotions?

- Do major promotions promote the purchase of less expensive tickets reducing yield?

If there is reasonably good evidence that major promotions increase ticket sales, are the increased ticket sales an efficient use of marketing dollars? Additionally, which type of major promotion is the most efficient? We’ll walk through an example of how to evaluate major promotions and then talk about measuring other forms of media exposure. This chapter may seem repetitive. We will analyze season data but in a slightly different way. Promotions will likely have small samples, putting us in a non-parametric world. This is a scary place where your favorite analytics tools may not work as intended.

8.1 Measuring the impact of promotions

Measuring the impact of promotions can be difficult. This analysis builds on analyses that we have already completed. We’ll begin with the now familiar season_data data set. This is a great spot to start evaluating promotions.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Season data structure

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

data <- FOSBAAS::season_data

data_struct <-

data.frame(

variable = names(data),

class = sapply(data, typeof),

values = sapply(data, function(x) paste0(head(x)[1:2],

collapse = ", ")),

row.names = NULL

)| variable | class | values |

|---|---|---|

| gameNumber | double | 1, 2 |

| team | character | SF, SF |

| date | double | 2022-03-27, 2022-03-28 |

| dayOfWeek | character | Sun, Mon |

| month | character | Mar, Mar |

| weekEnd | logical | FALSE, FALSE |

| schoolInOut | logical | FALSE, FALSE |

| daysSinceLastGame | double | 50, 1 |

| openingDay | logical | TRUE, FALSE |

| promotion | character | none, none |

| ticketSales | double | 42928, 25759 |

| season | double | 2022, 2022 |

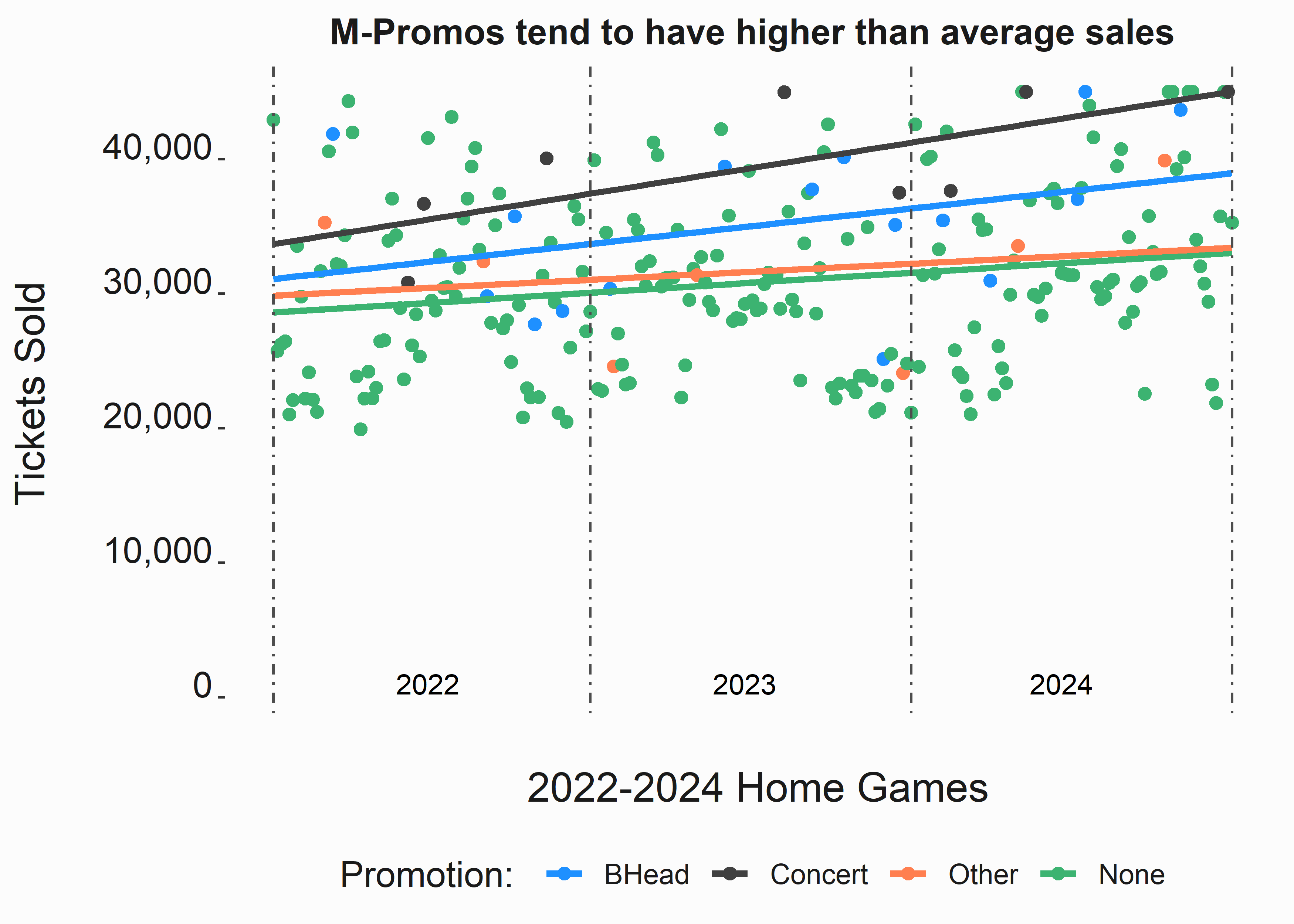

This data will allow us to examine the two most typical promotions a baseball team might conduct. Bobbleheads and Concerts are ubiquitous across sports. So it would lead you to believe that they are effective ticket drivers. However, there are many considerations.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Promotions by season

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

data$count <- seq(1:nrow(data))

x_label <- ('\n 2022-2024 Home Games')

y_label <- ('Tickets Sold \n')

title <- ("M-Promos tend to have higher than average sales")

ticket_sales <-

ggplot(data,

aes(x = count,y = ticketSales,

color = factor(promotion)),

group = promotion) +

ggtitle(title) +

xlab(x_label) +

ylab(y_label) +

scale_y_continuous(labels = scales::comma) +

geom_point(aes(y=ticketSales,x=count), size=2) +

geom_smooth(data=subset(

data,promotion == 'bobblehead' | promotion == 'concert' |

promotion == 'other' | promotion == 'none'),

method='lm',formula=y~x,se=FALSE,fullrange=TRUE,size=1.2) +

geom_vline(xintercept = 1, lty=4, color='grey30') +

geom_vline(xintercept = 81, lty=4, color='grey30') +

geom_vline(xintercept = 162, lty=4, color='grey30') +

geom_vline(xintercept = 243, lty=4, color='grey30') +

scale_color_manual(

breaks = c('bobblehead','concert','other','none'),

values=palette, name='Promotion: ',

labels=c("BHead","Concert","Other",'None')) +

annotate("text", x = 40, y = 1000,

label = "2022", color='black') +

annotate("text", x = 120, y = 1000,

label = "2023", color='black') +

annotate("text", x = 200, y = 1000,

label = "2024", color='black') +

graphics_theme_1 +

theme(

axis.text.x = element_blank(),

legend.position = "bottom",

panel.grid.major = element_blank(),

panel.grid.minor = element_blank(),

axis.ticks.x=element_blank()

)

Figure 8.2: Ticket sales by season

Let’s take a little closer look at this data. There are vast differences between many games. We saw in chapter 6 that a few variables could be used to predict sales. This is the type of graphic that can be misleading. If you took sales averages, promotions would appear to increase ticket sales. However, our product could be more consistent. The wide variation in sales contains seasonality, trends, and other endogenous factors influencing turnout.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Promotions by day of the week

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

x_label <- ('\n Promotion')

y_label <- ('Day of Week\n')

title <-

('Average Sales (10,000s) by promotion and day of week \n')

promos <-

data %>%

group_by(dayOfWeek,promotion,season) %>%

summarise(avgTickets = median(ticketSales))

tile_sales <-

ggplot(promos, aes(y=dayOfWeek,x=promotion)) +

facet_grid(.~season) +

geom_tile(aes(fill = avgTickets)) +

geom_text(aes(label = round((avgTickets/10000), 2)),

color='grey10') +

scale_fill_gradient(low = "white", high = "dodgerblue",

space = "Lab",

na.value = "grey10", guide = "colourbar") +

ggtitle(title) +

xlab(x_label) +

ylab(y_label) +

scale_y_discrete(limits=c('Mon','Tue','Wed','Thu',

'Fri','Sat','Sun')) +

scale_x_discrete(limits = c('bobblehead','concert',

'none','other'),

labels=c('bh','concert','none','other')) +

graphics_theme_1 + theme(

legend.position = "bottom",

axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 0, size = 10,

vjust = 0, color = "grey10"),

legend.title = element_text(size = 10, face = "plain",

color = "grey10"),

legend.text = element_text(size = 7, color = "grey10")

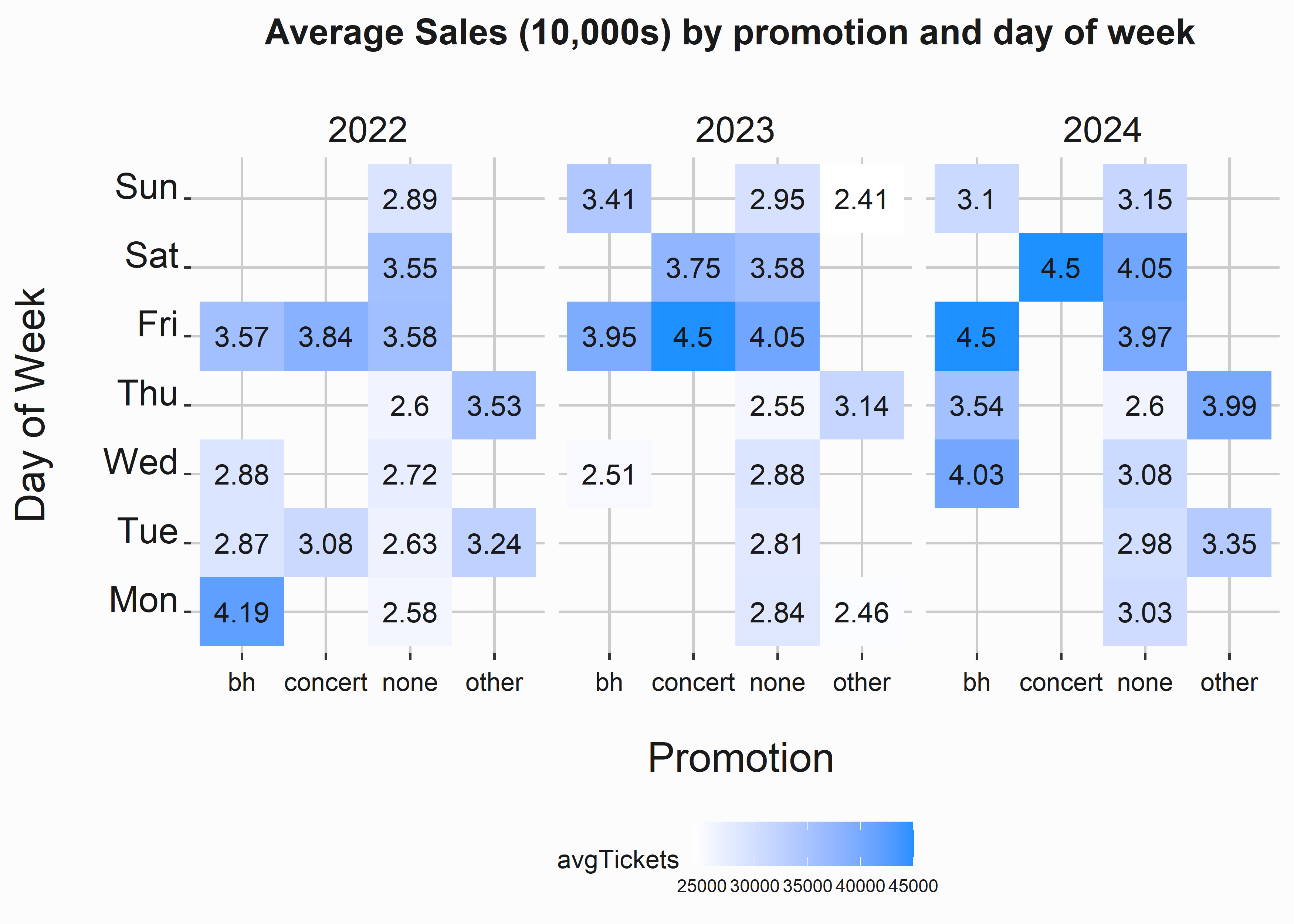

)This code chunk produces the tile plot in figure 8.3. We can see that concerts occur on the weekend. The same is true for Bobbleheads. How can we control for this to determine if they are impacting sales? We’ll look at this data in a few different ways for clarity. It is often helpful to experiment with graphics. The same data may tell other stories.

Figure 8.3: Ticket sales by season and day of week

Let’s take a brief aside and talk about color interpolation. There are several ways to interpolate colors in R. In addition, the virids library (Garnier 2021) is an exciting color package that produces very vivid results if used in the correct context. Give them a try.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Color interpolation

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

library(viridis)

scale_fill_viridis(direction = 1, option = "B",trans="log2")

scale_fill_distiller(palette = 'Greens',direction = 1)There does appear to be some difference between the days of the week. So let’s look at them in a slightly different way.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Promotions by season and day of week

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

data$count <- seq(1:nrow(data))

x_label <- ('\n 2022-2024 Home Games')

y_label <- ('Tickets Sold \n ')

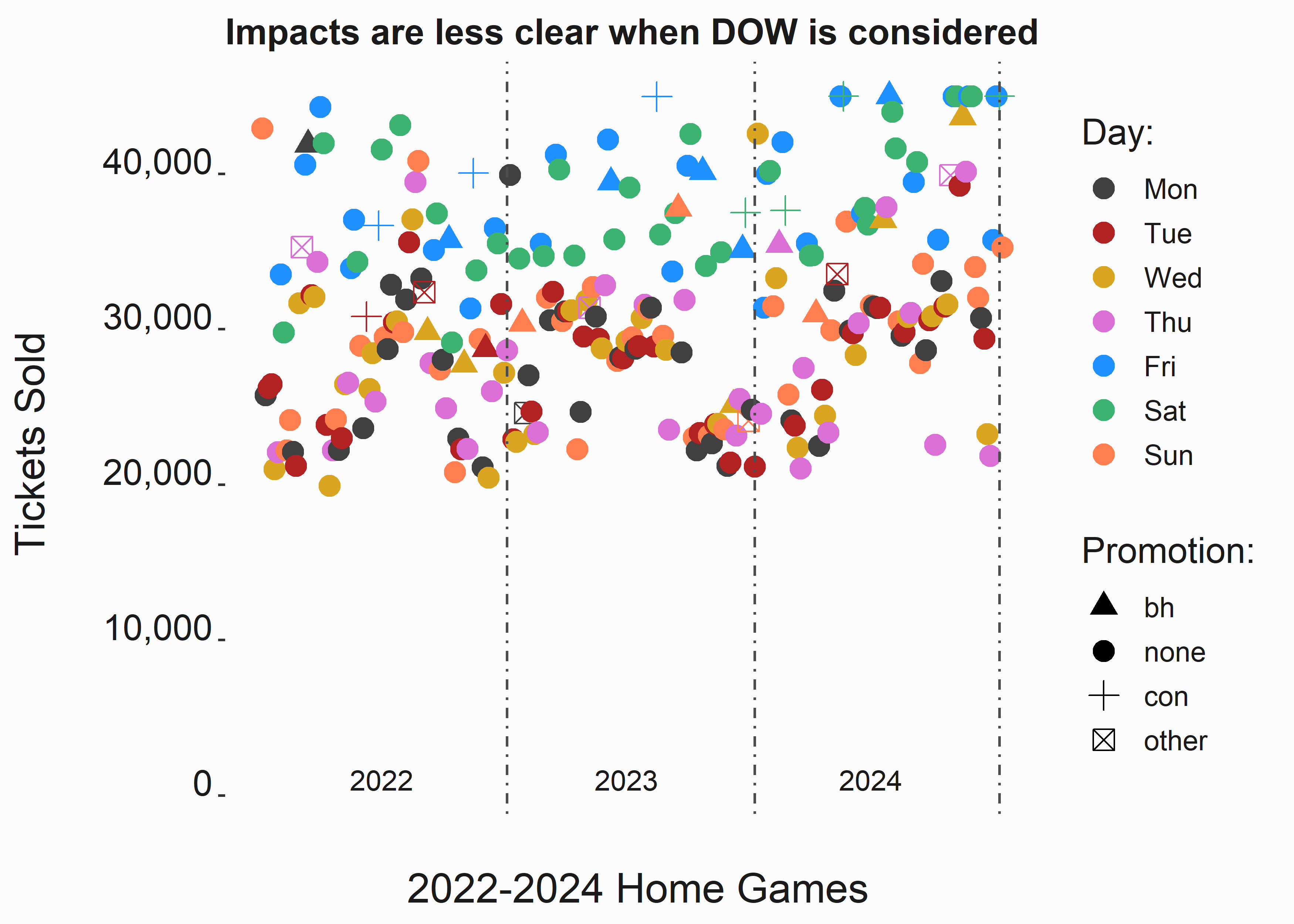

title <- ("Impacts are less clear when DOW is considered")

dow_sales <-

ggplot(data, aes(x = count,y = ticketSales,

color = factor(dayOfWeek),

shape = factor(promotion),

group =factor(dayOfWeek))) +

ggtitle(title) +

xlab(x_label) +

ylab(y_label) +

scale_x_continuous( breaks = 1:242) +

scale_y_continuous(labels = scales::comma) +

geom_point(aes(y=data$ticketSales,x=data$count), size=3.5) +

geom_vline(xintercept = 81, lty = 4, color ='grey30') +

geom_vline(xintercept = 162, lty = 4, color ='grey30') +

geom_vline(xintercept = 242, lty = 4, color ='grey30') +

scale_color_manual(breaks = c("Mon", "Tue",'Wed','Thu',

'Fri','Sat','Sun'),

values = palette,

name ='Day: ',

labels = c("Mon", "Tue",'Wed','Thu',

'Fri','Sat','Sun')) +

scale_shape_manual(

breaks = c('bobblehead','none','concert','other'),

name='Promotion: ',

values = c(17,19,3,7),

labels=c("bh",'none','con','other')) +

annotate("text", x = 40, y = 1000,

label = "2022", color='grey10') +

annotate("text", x = 120, y = 1000,

label = "2023", color='grey10') +

annotate("text", x = 200, y = 1000,

label = "2024", color='grey10') +

graphics_theme_1 +

theme(

axis.text.x = element_blank(),

legend.position = "right",

panel.grid.major = element_blank(),

panel.grid.minor = element_blank(),

axis.ticks.x = element_blank())We see a predictable pattern here that we could have assumed from the previous plot. But unfortunately, our analysis is confounded by many factors, and we can’t take sales at face value.

Figure 8.4: Ticket sales by season

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Box plot, sales by day of week

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

x_label <- ('\n 2022-2024 games by DOW')

y_label <- ('Tickets Sold \n ')

title <- ("Sales by DOW and promotion")

dow_sales_box <-

ggplot(data, aes(x = dayOfWeek,

fill = factor(promotion),

color = factor(promotion))) +

ggtitle(title) +

xlab(x_label) +

ylab(y_label) +

scale_y_continuous(labels = scales::comma) +

scale_x_discrete(limits=c("Mon", "Tue",'Wed','Thu',

'Fri','Sat','Sun')) +

geom_boxplot(aes(y=ticketSales)) +

scale_color_manual(

breaks = c('bobblehead','concert','none','other'),

values=c('grey40','grey40','grey40','grey40'),

name='Concert: ',

labels=c('bobblehead','concert','none','other'),

guide = 'none') +

scale_fill_manual(

breaks = c('bobblehead','concert','none','other'),

values=c(palette),

name='Promotion: ',

labels=c('bobblehead','concert','none','other')) +

graphics_theme_1 +

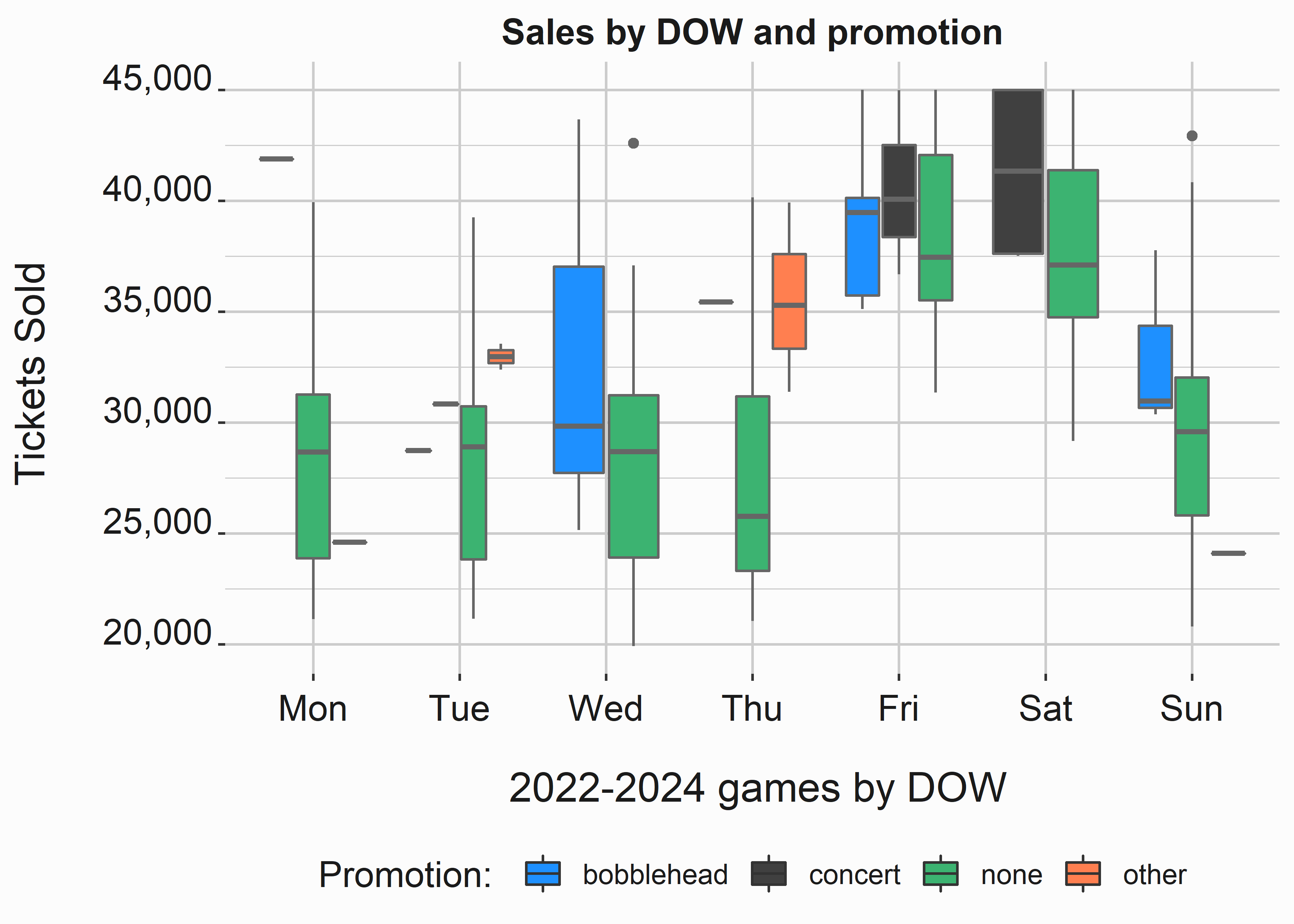

theme(legend.position = "bottom")This plot does an excellent job of discriminating between promotions. Concerts, bobbleheads, and other promotions generate more sales on average when the day of the week is considered. Could some other factor, such as the opponent, be having an impact here?

Figure 8.5: Ticket sales by season

8.1.1 Regressing on our data

As we have seen, regression takes some rigor to do correctly. It works best when you have a lot of data, which is a luxury we tend to have in only a few cases. We’ll go through another example, but we will look at our analysis slightly differently. We’ll also use a different framework this time. Why? Why not? There are many ways to do the same thing in R, and you will prefer some more than others.

We’ll use the tidymodels (Kuhn and Wickham 2022) package for this exercise 72. Tidymodels (like MLR3) will simplify the preprocessing and evaluation. We’ll begin by installing our libraries and doing a little processing on the data.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# preprocessing our data

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

library(tidymodels)

library(readr)

library(broom.mixed)

library(dotwhisker)

library(skimr)

library(dplyr)

data <- FOSBAAS::season_data

data <- data[,c("gameNumber","team","month","weekEnd",

"daysSinceLastGame","promotion","ticketSales")]Again, We are going to build a linear regression model. We also know that we are interested in how much promotions influence ticket sales. We’ll make one change to this data set with the function f_change_order() to make our results easier to interpret when we complete this exercise. This has to do with regression diagnostics output.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Alter promotions

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

f_change_order <- function(x){

if(x == "none"){"anone"}

else{x}

}

data$promotion <- sapply(data$promotion,function(x)

f_change_order(x))This is a sloppy approach to the issue we are trying to solve, but you’ll often resort to doing strange things while working with data. You’ll see what I mean in the following sections. If you want to reorder factor levels for a graph, you can do it with the factor function.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Alter factor levels

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

data$promotion <-

factor(data$promotion,

levels=c('none', 'bobblehead', 'concert', 'other'))We’ll use the rsample library (Silge et al. 2022) to build our training and test set. There are many ways to partition data, and we have used a different one every time. Find one that you like. We’ll split the data with twenty-five percent going to our holdout sample. Be aware that if you try to use your model to predict sales and a value in the new data, the model won’t work. This can be frustrating. We were making you aware. It will happen.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Splitting our data set

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

set.seed(755)

data_split <- initial_split(data, prop = .75)

train_data <- rsample::training(data_split)

test_data <- rsample::testing(data_split)Tidymodels leverages tidy principles and builds recipes up in layers. This is easier to work with than other frameworks. Pipes are just easier to read and understand. However, programmers might find the procedural nature of them irritating.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Build a recipe

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

sales_rec <- recipe(ticketSales ~ ., data = train_data)Piping in steps like dummy coding the variables is easy in this system. It makes preprocessing the data a mechanical exercise.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Add functions to the recipe

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

sales_rec <- recipe(ticketSales ~ ., data = train_data) %>%

update_role(gameNumber, new_role = "ID") %>%

step_dummy(all_nominal(), -all_outcomes()) %>%

step_zv(all_predictors())You can check your recipe with a couple of commands.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Check the recipe

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

data_test <- sales_rec %>%

prep() %>%

bake(new_data = test_data)

head(data_test)[c(4:9)]

#> # A tibble: 6 × 6

#> ticketSales team_ATL team_BAL team_BOS team_CHC team_CIN

#> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 25759 0 0 0 0 0

#> 2 26464 0 1 0 0 0

#> 3 29787 0 1 0 0 0

#> 4 35277 0 0 0 1 0

#> 5 40594 0 0 0 1 0

#> 6 32073 0 0 0 1 0We will select linear regression as the model to deploy.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Define a model

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

lm_model <- linear_reg() %>%

set_engine('lm') %>%

set_mode('regression')Tidymodels uses the concept of workflows to process the regression steps.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# build a workflow

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

sales_wflow <- workflow() %>%

add_model(lm_model) %>%

add_recipe(sales_rec)

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# build a workflow

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

set.seed(755)

folds <- vfold_cv(train_data, v = 10)

sales_fit_rs <- sales_wflow %>%

fit_resamples(folds)

cv_metrics <- collect_metrics(sales_fit_rs)Finally, we’ll apply the workflow and fit the model to the training data set.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Run the model and extract the results

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

sales_fit <- sales_wflow %>%

fit(data = train_data)

results <- sales_fit %>%

extract_fit_parsnip() %>%

tidy()You can also extract the model.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# build a workflow

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

model <- extract_fit_engine(sales_fit)

model_metrics <- glance(model)We know that we have sample size issues with this data. Can we trust these coefficients?

We can use the coefficients in this model to help us explain specific promotions’ impact relative to other variables. For example, a bobblehead is worth about 4,062 ticket sales.

However, this is only part of the story. Concerts, bobbleheads, and other promotions have different costs. For a concert, costs could be very high. You have a lot to consider:

- Talent fees

- Production fees

- Replacing damaged turf

- Lighting

This list is far from exhausting, but the electric bill at a stadium may shock you. A promotion such as a bobblehead has a much more discrete cost. You have a per-unit fee and incur the costs of storing and dispensing the item. This makes the calculus reasonably simple if you only consider the dimension of ticket sales. Concerts may increase other ancillary purchases, such as food and beverage. Additionally, the excess tickets sold for a bobblehead may be the least expensive seats in the stadium. Which one will net the most revenue?

8.2 How to place promotions on a schedule

We covered a top-down approach to forecasting in chapter 6. How do you know which dates to select for a particular promotion? The calculus typically revolves around two considerations:

- Maximizing ticket impact

- Maximizing revenue impact

How do you know if you are making these takeoffs? Specific scenarios may make the correct decision unclear. Let’s look at our example from chapter 6. Now that we have confirmed that bobbleheads and concerts increase ticket sales let’s add another bobblehead. Where should we add this promotion? The event scores we produced for the season_2025 data set may give us some clues. There are also many qualitative considerations that we will discuss.

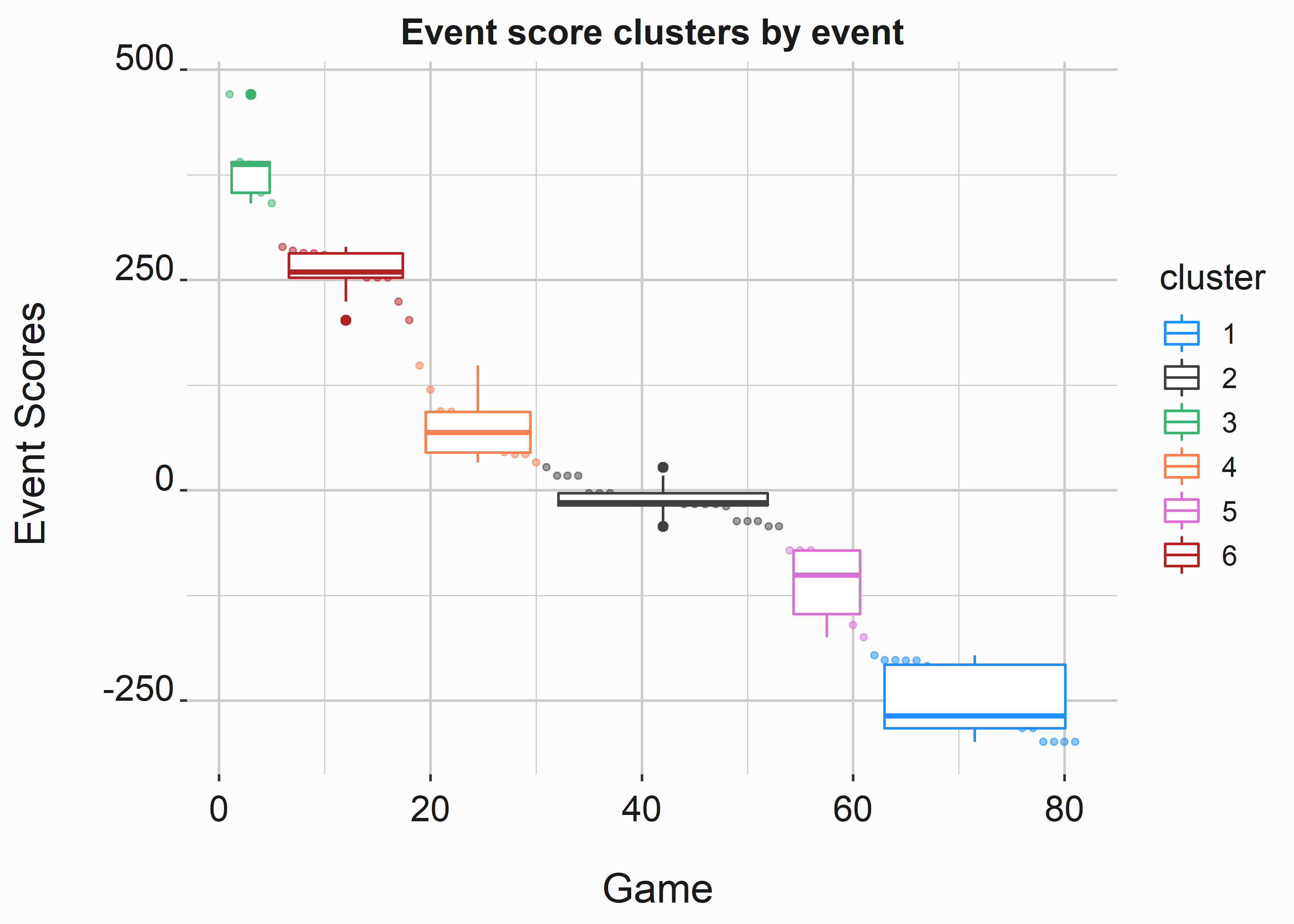

Let’s start by visualizing our data. Where do the boundaries exist between event scores? We clustered this data earlier and will use these clusters to identify candidates for a promotion.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Clustered events

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

season_2025 <- read.csv('files/season_2025.csv')

season_2025$cluster <- factor(season_2025$cluster)

x_label <- ('\n Game')

y_label <- ('Event Scores \n')

title <- ('Event score clusters by event')

es_box <-

ggplot2::ggplot(data = season_2025,

aes(x = order,

y = eventScore,

color = cluster)) +

geom_point(size = 1,alpha = .5) +

geom_boxplot() +

scale_color_manual(values = palette) +

scale_y_continuous(label = scales::comma) +

xlab(x_label) +

ylab(y_label) +

ggtitle(title) +

graphics_theme_1

Figure 8.6: Event attractivness range by cluster

If our goal is to maximize ticket sales, we should plan something other than these promotions on games where there is a possibility that the game will sell out. If a sellout is within the confidence interval for a sellout, it should be disqualified from consideration. Let’s take a look at some candidate dates. We’ll assume that we want to maximize sales. We decided to go this route because the ancillary revenue associated with concessions and retail will compensate for the ticket premium we are forgoing. However, we are also looking for games with more potential in terms of higher prices. Let’s start by identifying the borders of our clusters. An easy way to do this is to use the duplicated function. Then, we’ll reverse the output so that it makes more sense for our header.

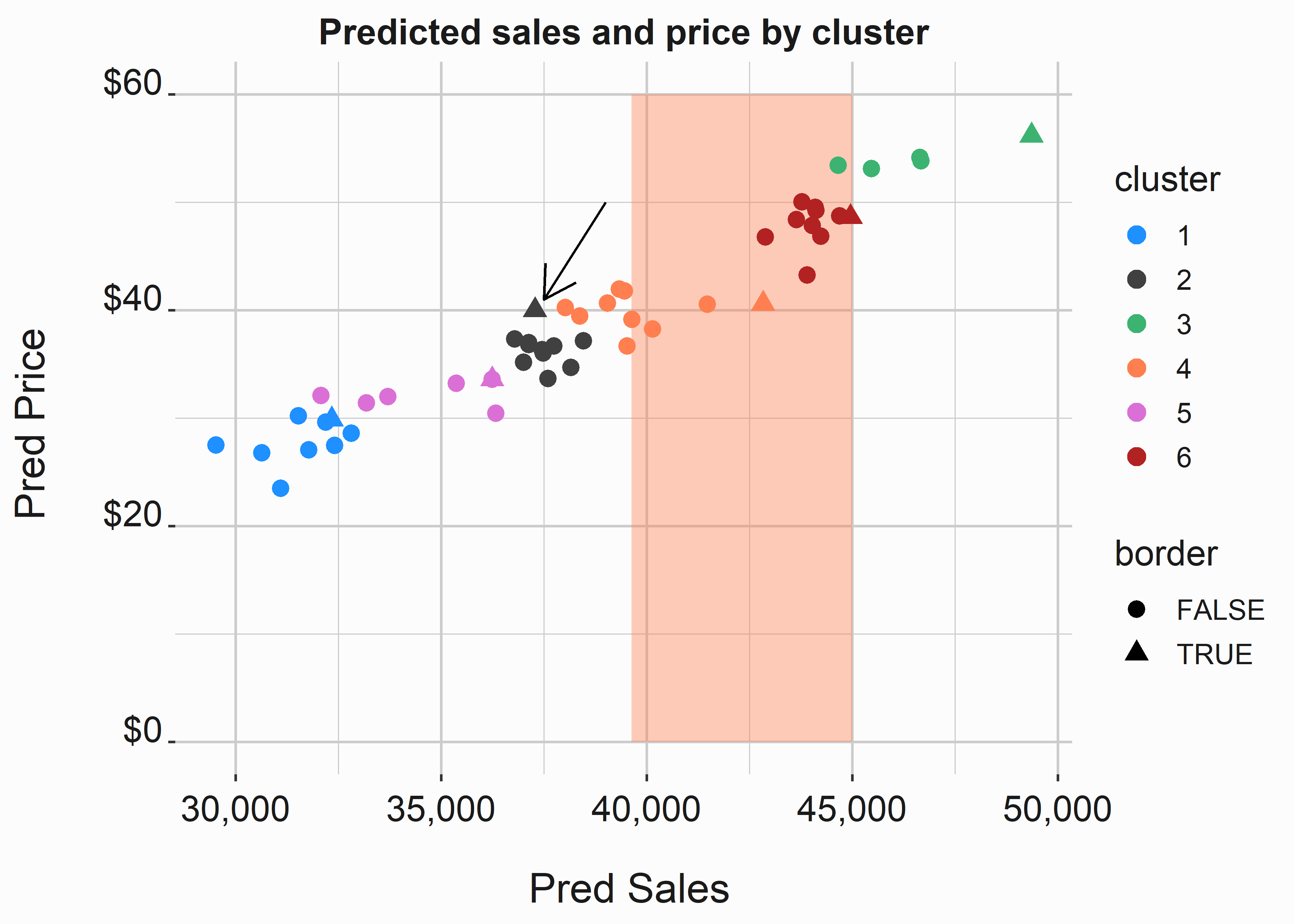

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Identify game breaks

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

season_2025$border <-

ifelse(duplicated(season_2025$cluster) == TRUE,FALSE,TRUE)Look at a scatter plot of predicted prices vs. ticket sales. We know that there is some interaction between sales and prices. We also know how much a promotion such as a bobblehead may impact sales. We’ll use the upper bound of the confidence interval to give us an idea of games that might not be the best candidates for the bobblehead. For example, if we select one of the games in the band, we may miss out on the opportunity to sell more tickets because we exceed capacity. On the other hand, one of these games might be more attractive if we want to maximize revenue because the price premium overwhelms the capacity constraint.

We could get a lot fancier here with our confidence interval and estimates, but this analysis doesn’t warrant it. Simple is often good.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Identify candidate games

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

season_2025$cluster <- factor(season_2025$cluster)

x_label <- ('\n Pred Sales')

y_label <- ('Pred Price \n')

title <- ('Predicted sales and price by cluster')

es_scatter <-

ggplot2::ggplot(data = season_2025,

aes(x = predTickets,

y = predPrices,

color = cluster,

shape = border)) +

annotate("rect", xmin = 45000 - confint(model)[36,2],

xmax = 45000,

ymin = 0, ymax = 60,

alpha = .4, fill = 'coral') +

geom_point(size = 3,alpha = 1) +

geom_segment(aes(x = 39000, y = 50,

xend = 37500, yend = 41),

arrow = arrow(length = unit(0.5, "cm")),

color = 'black') +

scale_color_manual(values = palette) +

scale_x_continuous(label = scales::comma) +

scale_y_continuous(label = scales::dollar) +

xlab(x_label) +

ylab(y_label) +

ggtitle(title) +

graphics_theme_1

Figure 8.7: Predicted sales and prices by cluster

We can see which games are the best candidates. Let’s look at the border games for clusters 2 and 5. Then, let’s look at our candidate game to see if it is appropriate for adding a promotion.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Get Confidence Intervals

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

candidate <- subset(season_2025,

season_2025$border == T & cluster == 2)| team | date | dayOfWeek | month | predTickets | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 59 | BAL | 2025-05-13 | Tue | May | 33705.15 |

This game is in late summer and already commands a high price. There isn’t another major promotion on this night, and there is plenty of headroom on sales. This game looks like a great night to add a promotion. However, there are other considerations.

Promotions often have sponsors, and they may have a preference for when their specific promotion takes place. You also need to consider the promotional item. For example, a bobblehead may need six months of lead time. This analysis needs to take place well in advance so that it can be produced and adequately messaged. Additionally, the theme of the item may not be appropriate for other promotions occurring simultaneously. Finally, it would be best to consider what is happening in the region. Do you have competition from another venue or event on that night?

8.3 Evaluating external and internal marketing assets

This is not a marketing textbook, but to cover the major analytics categories for a sports team, I had to cover marketing. We have also covered several subjects that are directly related to marketing, such as segmentation and pricing. However, we are discussing something different here. Although measuring media assets is a big business, the phrase “It’s Turtles all the way down” comes to mind. When you get to the bottom, some arbitrary figure is likely being used to gauge the value of signage or a social media post. This is also where we can briefly talk about internal marketing assets. A pro sports team might sell some tickets, media, and merchandise, but it is also a marketing platform. We’ll discuss them both in this section.

Honestly, this sort of analytics is slightly dull. You aren’t dealing with concrete truths. A marketing asset is worth what someone is willing to pay for it. Ultimately, the worth tends to be gauged in one of two ways; How many people can be exposed and the quality of that exposure. The more eyes that are on your platform, the better. If you are also good at putting advertisements in front of the most relevant audiences, you become Google.

Advertising is big business, and trying to prove how much it is worth to a pro sports team is analogous to astrology. Digital giants have their methods of attribution. I have always looked at these methods with some skepticism. If my business sells advertising, what incentive do I have to tell you it doesn’t work?

Overall, these assets are usually evaluated on some form of exposure equivalency. This impressions-based formula would look something like this:

\[\begin{equation} \ {Value} = {Exposure} * {Quality} * {Costs} \end{equation}\]

The arbitrary cost I am talking about references some value associated with outreach. How much does it cost to reach a potential customer? I don’t mean to sound cynical, but this number is difficult to estimate.

8.3.1 External marketing assets

Marketing assets are incredibly varied. The internet is a marketing platform. Additionally, messaging varies throughout the year. For instance, Brand messaging may predominate during the off-season. However, ticket sales messaging will be the predominant category during the season.

I lump digital marketing into two categories—platform digital and local digital.

- Platform digital marketing involves the tech giants. They each have sophisticated methods to reach customers and potential customers. Advertising through social media is still new in the scheme of advertising. Increasingly, more money is being spent in these areas. It is easier to attribute sales to your spend using these mediums because tracking customers during the process is easy. However, that is becoming more difficult. You can classify the advertising through these platforms as display, video, Social, or Audio. The major players in this arena include:

- Google Display Network

- Amazon

- Youtube

- TikTok

- Spotify

Each of these platforms has its attribution methodologies. These methodologies can also vary. If you want to make an effort to attribute sales through these channels, you have to combine their capabilities with old-school tricks. For instance, a special offer may only be advertised through one of these channels. So how can you attribute sales to an outlet such as Facebook? Three main methods are leveraged:

- First touch/Last touch: If a fan purchases tickets, what is the first or last platform they visited? We’ll attribute the entire purchase to this platform.

- Weighted models: These models would attribute some portion of the sale to each advertising touchpoint. Weighted models may also decay over time. For instance, if it has been fourteen days since the touchpoint, we no longer attribute the sale to a portion of the marketing engine.

- Algorithmic models: These models are custom-built and might use regression or some other tool to more accurately weight touchpoints.

This means the analytics involved here looks more like a flow chart diagram than a math equation. However, this is only sometimes true. In sports, we typically deal with relatively small transactions that occur on a predictable cadence. There are better scenarios for using algorithmic methods. There is an expression that I think of here “Good is the enemy of great.” I wouldn’t overthink this subject.

Local digital marketing refers to leveraging display through local mechanisms. This would include the city or regional newspaper websites. Fandom will decrease the further an individual lives from the local market. Therefore, these channels will typically have a good readership in your local market.

Search engine marketing is a separate category from the display, and it has some issues in the context of sports. We discussed them briefly earlier. With efforts to flatten secondary markets, this form of marketing may be less critical for clubs in the future. If someone is typing “game hen tickets” into a search engine, we know they wanted tickets. Do we care where they buy them? Sometimes. However, this is a losing strategy. You have to depend on the individual clicking an ad for attribution, and you can’t beat the secondary market makers in terms of spend.

Television advertising is still crucial in the marketing budget. However, traditional broadcasts have declined for years. The T.V. and cable industries are in crisis. Younger consumers are altering their consumption habits at alarming rates. Therefore, this channel will continue to wane in importance.

Radio. Buying and selling radio spots also has a multitude of considerations. How is this measured? Third-party researchers pay people to allow them to track consumption habits and then extrapolate. Additionally, terrestrial radio broadcasts have decreased in popularity due to subscription services.

Outdoor Advertising. Out-of-home advertising is also varied. Highway signage is the biggest category in outdoor advertising. There are many local players, but a few huge players also dominate this arena. Prices also vary considerably. This advertisement is inexpensive, widely available, and can be purchased in precise increments.

Print. Traditional print advertising would include taking out advertisements in newspapers or magazines. This channel has dramatically decreased in importance over the years.

Many of these channels are difficult or impossible to measure. Building formal experiments around how effective print ads aren’t a top priority in our business. How do you build a strategy around your marketing mix? The sales cadence is probably the best place to start. You have to start with what you know. We know when sales typically happen on a game-by-game basis. Understanding the customer journey should be a critical part of your marketing strategy. This will inform your strategy more than anything. You can also dramatically decrease spend in channels that aren’t readily measurable.

There is also a paradox in sports related to marketing. When the team is good, it will appear that your marketing plays a part in the success. This high-on-high strategy works when you use price as a lever. However, how effective is marketing when a team isn’t good? If you spend the same amount in the same places, you expect some level of baseline success. I wonder if this can be validated. From a strategic standpoint, what does this mean? It means you should be skeptical and ruthlessly test and experiment.

8.3.2 Internal marketing assets

Internal assets are very similar to external assets. However, there is an added wrinkle. An association with a pro sports team creates added brand equity. This doesn’t happen when you advertise through Facebook. Additionally, there is some tangential association with the other brands advertising with the team. This makes evaluating the value of a piece of signage or a social media post delivered by the team much more difficult.

How would you calculate the value of a piece of signage in the outfield of our ballpark in Nashville? This process would involve a few steps. You would likely need to engage a third party to get information on Television and radio. A few large media research companies specialize in this sort of research. The basic process works like this:

- Calculate the amount of exposure. How many people see the sign through each channel?

- Evaluate the quality of that exposure. How often is the asset visible.

- Calculate a unit value for the audience through each channel

- Build a coefficient into the calculation that takes into account brand association

What sorts of internal assets are we discussing? A sports team has a large toolbox in terms of advertising assets. This includes:

- In-venue signage

- Television and radio broadcasts

- Category rights for co-branding

- Social media posts

- Community outreach and foundations

- Uniform patches or logos

- Venue naming rights

Each of these assets varies. For instance, signage is a broad category, with the best inventory being located behind homeplate, in the outfield, and around the marquee. As a result, the costs associated with these assets will vary considerably. Additionally, the value of these assets could be influenced by in-market reference prices and competition.

The best place to begin here is by analyzing the rate card. How much inventory is being used, and how much isn’t being utilized? Are there imbalances? Are there opportunities to create new inventory, such as on the foul poles? Many of your sponsorship deals will be on staggered multi-year terms. Exclusivities are also common and restrict access to specific categories.

Objectively justifying a sponsorship can be difficult. From a buyer’s perspective, reconciling opportunities may take work. While building a decision matrix of options is relatively simple, taking brand considerations into account is needed.

8.4 Key concepts and chapter summary

Promotions are a response to having less demand than supply and can be very difficult to evaluate. We covered a few high-level topics:

- Evaluating promotion efficacy

- building a model using the TidyModels framework

- Putting promotions on a schedule

- Valuing internal and external marketing products

We learned that some promotions have an impact, and some appear not to have an effect. This can vary by market, but some promotions work better. Marginal costs associated with a promotion should always be considered. There are also more qualitative considerations such as when the last promotion occurred, lead time, and sponsorship considerations.

The tidyModels framework is an easy way to take care of the mechanics of model construction. It handles various machine learning tasks and is a flexible method to try multiple techniques.

Placing promotions on a schedule is related to pricing. There are complex interactions between price and demand. Sports is unique because the product has multiple qualitative considerations, such as win-loss record, playoff chances, seasonality, and promotional items.

Evaluating the return on marketing spend takes a lot of work. Many assets defy valuation. Pricing internal assets can be challenging but typically has three considerations: viewership, engagement quality, and brand association.