7 Lead Scoring

What if someone told me they would pay me $50,000 if I sold four season tickets to someone in the next twenty-four hours? What would I do? If the tickets were less than $50,000, I could always buy the tickets and collect the surplus. How could I increase the likelihood that I sold those four season tickets?

- I could look for lapsed purchasers

- I could look for abandoned carts on our website

- I could call individuals who have yet to renew season tickets

- I could beg family and friends to purchase

- I could call a ticket broker and ask them to buy tickets

There are lots of tactics you could deploy to make sure that you are picking all the low-hanging fruit. However, it is unlikely that you ever get to the point where you pick up a telephone and begin calling phone numbers. So can we approach this problem more analytically?

Lead scoring is fundamental to sales campaigns. You can qualify leads in many ways, but the goal is always the same. You are ordering your leads more efficiently so that your sales efforts can maintain greater efficiency. Warm leads are critical, and if someone has yet to interact with your brand, they are likely a less efficient use of your time. Working in marketing always reminds me of this one-hundred-and-thirty-year-old quote:

“Half the money I spend on advertising is wasted; the trouble is I don’t know which half.”

— John Wanamaker

Lead scoring should assist you in evaluating your direct sales efforts and help to maximize ROI in that context. However, there are several considerations. First, how do we assess a lead?

- Customer Lifetime Value?

- The likelihood of purchasing during this sales cycle

- Recent, frequency, monetary value

Accessing a lead is also a judgment call predicated on how sales and marketing teams are incentivized. Always consider compensation packages. Compensation is designed to incentivize behavior. However, it may need to be optimized to achieve organizational goals.

7.1 Recency, frequency, and monetary value

RFM scores are often described as a poor-man’s analytic technique. The basic premise is to score sales candidates along three dimensions and to build lists comprising cohorts with the highest aggregate scores. How might this work in practice?

Let’s assemble an ad hoc data set to demonstrate how RFM scores might work.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# RFM data

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

library(dplyr)

demo_data <- FOSBAAS::demographic_data[,c(1,4)]

set.seed(44)

demo_data <- demo_data %>%

mutate(

lastInteraction = abs(round(rnorm(nrow(demo_data),50,30),0)),

interactionsYTD = abs(round(rnorm(nrow(demo_data),10,5),0)),

lifetimeSpend = abs(round(rnorm(nrow(demo_data),10000,7000),0))

)We have added three columns to the customer file:

- How long the last interaction happened in days

- How many interactions have happened

- How much has been spent by the customer

| custID | nameFull | lastInteraction | interactionsYTD | lifetimeSpend |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MBT9G0X70NTI | Philip Riddle | 70 | 7 | 11554 |

| QTR3JJJ5J6GJ | Evelyn Campos | 51 | 14 | 4480 |

| HOMV3XQW32LW | Sarah Valdez | 5 | 13 | 3986 |

| RJ7CCATUH4Q1 | Pamela Munoz | 46 | 11 | 9454 |

| 9GZT5Z5AOMKV | Ronald Ortiz | 14 | 11 | 11336 |

| S0Y0Y2454IU2 | Nicole Barry | 10 | 8 | 9259 |

There are many ways to apply scores here. We will take a similar approach to score events but add one extra step. RFM scores are traditionally built from one to five, with five being the highest.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Function to calculate FRM scores

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

demo_data$Recency <- -scale(demo_data$lastInteraction)

demo_data$Frequency <- scale(demo_data$interactionsYTD)

demo_data$MonetaryValue <- scale(demo_data$lifetimeSpend)

# Produce quantiles for each scaled value

r_quant <- unname(quantile(demo_data$Recency,

probs = c(.2,.4,.6,.8)))

f_quant <- unname(quantile(demo_data$Recency,

probs = c(.2,.4,.6,.8)))

m_quant <- unname(quantile(demo_data$Recency,

probs = c(.2,.4,.6,.8)))

# Function to evaluate RFM score

f_create_rfm <- function(quantList,number){

if(number <= quantList[[1]]){'1'}

else if(number <= quantList[[2]]){'2'}

else if(number <= quantList[[3]]){'3'}

else if(number <= quantList[[4]]){'4'}

else{'5'}

}Now we can apply the function to our data set. We could generalize this more. We could also use an apply function. For this sort of exercise, we aren’t concerned with extreme efficiency. We want to demonstrate the mechanics. We’ll use lists and for loops to accomplish our task. If we had to repeat this exercise often, there are better practices than daisy chaining for loops. Try to copy and paste at most three times. You’ll make errors.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Create final RFM values

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

value <- list()

j <- 1

for(i in demo_data$Recency){

value[j] <- f_create_rfm(r_quant,i)

j <- j + 1

}

demo_data$r_val <- unlist(value)

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

value <- list()

j <- 1

for(i in demo_data$Frequency){

value[j] <- f_create_rfm(f_quant,i)

j <- j + 1

}

demo_data$f_val <- unlist(value)

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

value <- list()

j <- 1

for(i in demo_data$MonetaryValue){

value[j] <- f_create_rfm(m_quant,i)

j <- j + 1

}

demo_data$m_val <- unlist(value)

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

demo_data$RFM <- paste(demo_data$r_val,

demo_data$f_val,

demo_data$m_val, sep = '')Now each customer has an RFM score that can be used to build campaigns. First, let’s subset a group for a campaign. We’ll select customers that have interacted the most recently, the most frequently and have tended to spend the most.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Create final RFM values

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

top_prospects <- subset(demo_data,demo_data$RFM == '555')| nameFull | r_val | f_val | m_val | RFM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ryan Livingston | 5 | 5 | 5 | 555 |

| Russell Church | 5 | 5 | 5 | 555 |

| Stephen Lawrence | 5 | 5 | 5 | 555 |

| Karen Waller | 5 | 5 | 5 | 555 |

| Elizabeth Clements | 5 | 5 | 5 | 555 |

| Teresa Compton | 5 | 5 | 5 | 555 |

RFM scores can be helpful for some segmentation schemes and lead scoring. However, there are better ways to accomplish the same goal. Lead scoring is as close as we get to discussing Customer Relationship Management (CRM) in this book. It is also a fundamental component of CRM. The following examples will take you through a more sophisticated example and use an analytics framework that will make regression and machine learning easier.

7.2 Scoring season ticket holders on their likelihood to renew

With advancements in hardware and software, lead scoring has become a commodity. You can leverage several techniques, including random forests, gradient boosting, logistic regression, or even deep learning with a tool such as Tensorflow, without getting penalized because of time and costs. Take a minute to appreciate this fact. It is amazing. Amazon, Google, and others are improving this process through AWS and GCP. This example will demonstrate how machine learning is applied to real-world problems. We’ll frame this problem around a common question that is asked every year and in every club in sports.

The ticket sales service manager wants to understand which accounts are less likely to renew their season tickets.

We’ll use the mlr3 library (Bischl et al. 2021) to demonstrate several machine-learning algorithms. The package mlr3 is similar to caret (Kuhn 2022), which has been refactored into tidymodels (Kuhn and Wickham 2022). Caret was a great library that sought to create a unifying API for scores of other R libraries. We’ll look at tidymodels in the next chapter. Mlr3 is reminiscent of scikit-learn in Python. If you like using Python for analysis, mlr3 will feel familiar.

While we can call our functions directly, this library makes the process much easier. The lack of consistent frameworks in R is one of the language’s biggest drawbacks. Additionally, mlr3 has excellent documentation 67.

Using a framework also comes with some issues.

- You’ll have to learn it, which adds complexity to the task.

- Errors (especially in beta versions) can be frustrating to troubleshoot

- They can work more slowly than the libraries that are used for the task

However, you’ll be better off leveraging a framework in the long run. This is because frameworks make the essential tasks of machine learning much more systematic and repeatable, especially when it comes to benchmarking.

Let’s also discuss the package data.table (Dowle and Srinivasan 2021) here. data.table is a powerful tool that underlies many popular packages. While it has many uses, it can be more confusing than dplyr (Wickham, François, et al. 2022). Nevertheless, it is one of the pillars that holds up much of the R universe. If you have been using Python, datatable will remind you of pandas (team 2020). If you are working with large data sets, datatable will be helpful to learn.

7.2.1 Implementing a lead-scoring project

A random forest is an excellent tool for classification and can forecast more than two classes. Logistic regression is typically used for binary classes (renewed, did not renew) and should probably be your first step. However, there are forms of logistic regression that will handle multi-class problems. We’ll take a look at both tools. In practice, a random forest handles a wide variety of the issues you will face at a club very well.

Missing data or orphan cases can make these tasks extremely frustrating. There is no guarantee that your model will converge. We stated earlier that most of your time would be spent organizing your data. You’ll be much happier if you put the hours into getting your data in the proper spot. The fun part of these exercises is the modeling. However, it ends up being the part you spend the shortest time working on. I hope the high is worth the lows to you.

Additionally, we should follow the process outlined in chapter 4. We’ll do this to demonstrate that it isn’t managerial B.S. Structuring projects is critical when working in teams or in a distributed fashion. Let’s remind ourselves of the basic steps we want to follow:

- Define a measurable goal or hypothesis

- Data collection

- Model the data

- Evaluate your results

- Communicate the results

- Deploying the results

7.2.1.1 Defining our goal

We are going to use multiple years of season ticket holder renewal data. We also have a problem statement:

We need to identify season ticket accounts that are less likely to renew.

Our output will be a score that can be used to compare customers against one another. We’ll need to look for features that predict whether someone will likely renew their tickets. This feature might be ticket usage or tenure. We don’t know.

The rub here is that we can’t help improve the prospects that someone might renew. So what levers can we pull? Building a helpful model that predicts renewals for finance is one thing, but we are trying to impact renewals for sales. We’ll need to think carefully about the insight that we gather. We may find something that we didn’t know we were looking for. From that perspective, success can be gauged in several ways.

7.2.1.2 Understanding the data set

Our data set includes several features, including an account, whether they renewed, and several traits related to their season tickets. The data is located in the FOSBASS package. You can see how the data is created in section 2.2.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# access renewal data

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

library(FOSBAAS)

library(dplyr)

mod_data <- FOSBAAS::customer_renewalsThis data set contains several years of data. It looks like something you would find at a club, and will behave appropriately. Let’s take a look at the structure of this data:

| variable | class | values |

|---|---|---|

| accountID | character | WD6TDY7C151R |

| corporate | character | i |

| season | double | 2021 |

| planType | character | p |

| ticketUsage | double | 0.728026975947432 |

| tenure | double | 2 |

| spend | double | 4908 |

| tickets | double | 6 |

| distance | double | 61.6614648674555 |

| renewed | character | nr |

This data is relatively simple. We have several columns that appear helpful. This data set is also already clean, but let’s refer to section 4.3.1 in chapter 4 to ensure we cover all of our bases. We know this data is in good shape, but we still have to deal with significant issues you face when running some operation on your data.

- What sort of analysis mechanism will be helpful to solve this problem?

- Is this data structured and formatted so I can use it?

- Will missing values or other systematic issues cause a problem?

Question one is easy. We can refer to our chart in section 4.4. This is an example of calculating future numerical values.

For question two, different analysis techniques require other formats. We can see that a couple of columns are categorical. Let’s go ahead and create two data sets. We’ll dummy code our categorical data so that one data set only contains numerical values.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Dummy code and alter data frame for all numeric input

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

d1 <- as.data.frame(psych::dummy.code(mod_data$corporate))

d2 <- as.data.frame(psych::dummy.code(mod_data$planType))

mod_data_numeric <- dplyr::select(mod_data,ticketUsage,

tenure,spend,tickets,

distance,renewed) %>%

dplyr::bind_cols(d1,d2)| ticketUsage | tenure | spend | tickets | distance | renewed | i | c | f | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.7280270 | 2 | 4908 | 6 | 61.661465 | nr | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 0.9921047 | 19 | 16410 | 2 | 19.534115 | nr | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 0.9791836 | 5 | 7248 | 3 | 5.738407 | r | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 0.8221204 | 23 | 6442 | 2 | 1.280233 | r | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 0.9836147 | 5 | 19800 | 8 | 19.028667 | r | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 0.9032806 | 3 | 6640 | 4 | 15.584057 | r | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

For question three, we can do a little preparation on our standard data set. We’ll eliminate a few columns we won’t use and turn our response variable into a factor. We know there isn’t missing data, so that we will skip that part. We have already covered how to deal with it.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Prepare the data for analysis

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

mod_data$renewed <- factor(mod_data$renewed)

mod_data$accountID <- NULL

mod_data$season <- NULLIn terms of prep work, we are ready to go. This chapter is designed to cover data modeling in more detail, so it is optional anyway. We also didn’t have to worry about data collection. What other data might be interesting to have here?

Additionally, I would like to briefly cover a topic that deserves more attention than we are about to give. Maps. Geography is essential for sales, marketing, and corporate sponsorship groups. In this context, we’ll see how geography will further impact sales and marketing strategy in this chapter.

7.2.1.2.1 Understanding geography and building maps

Geography plays a prominent role in selling tickets to sporting events. The importance of this role is especially true for sports with more games, such as baseball. Coupling the digital and physical assets of the club may make this less critical holistically. However, geography is and will remain a crucial point of consideration for ticket sales.

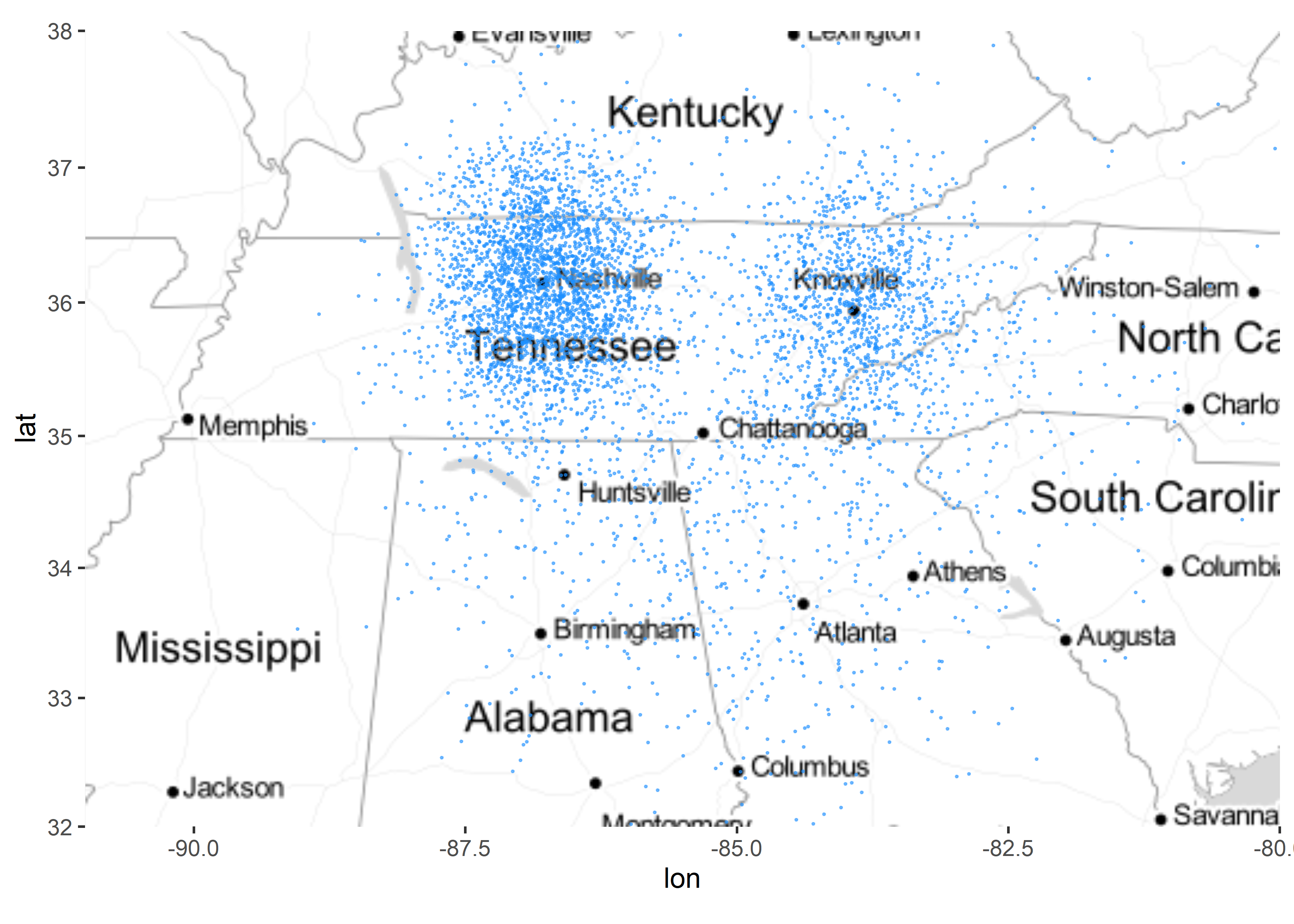

R isn’t the best way to do this, but it is easy to accomplish it in the same analysis platform. GIS is a large field that is outside this book’s scope. However, R has multiple libraries devoted to maps, and it is a good choice if you are looking for something other than very high-quality graphics. This map was created using stamen maps68, an open-source tool that can be used for various projects.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Using R to visualize geographic data

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

library(ggmap)

library(ggplot2)

demos <- FOSBAAS::demographic_data

demos <- demos[sample(nrow(demos), 5000), ]

map_data <- subset(demos,demos$longitude >= -125 &

demos$longitude <= -67 &

demos$latitude >= 25.75 &

demos$latitude <= 49)

us <- c(left = -91, bottom = 32, right = -80, top = 38)

map <- get_stamenmap(us, zoom = 6, maptype = "toner-lite") %>%

ggmap()

geographic_vis <-

map +

geom_point(data = map_data,

mapping = aes(x = longitude, y = latitude),

size = .2,alpha = .5, color= 'dodgerblue')

These maps could be better, but they are easy to execute and can give you much of the same insight you would get from a more sophisticated product such as ArcGIS 69. R also makes it easy to access google APIs, allowing you to Geocode addresses and perform many other interesting tasks with geographic data. You can find a multitude of informative demos online.

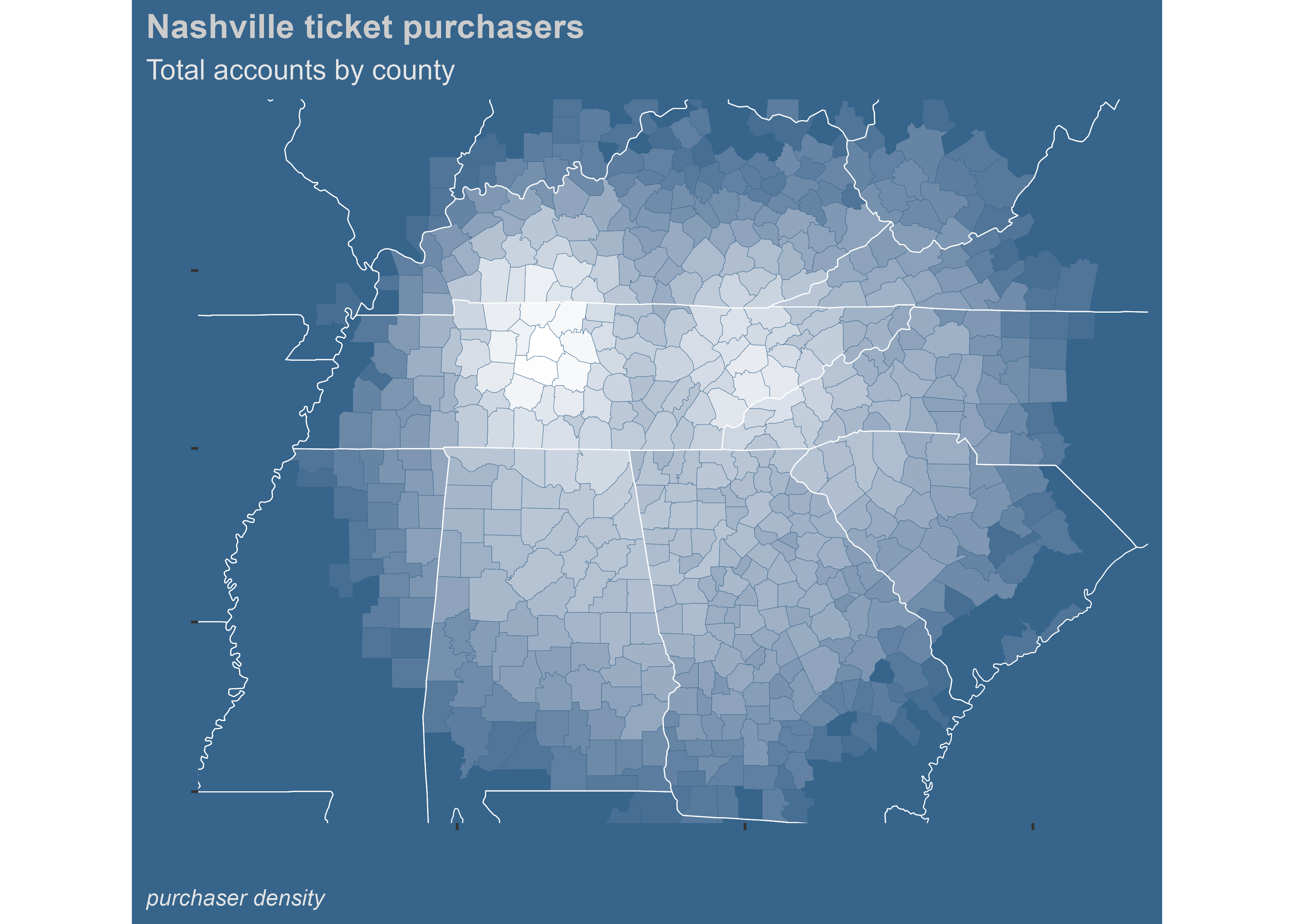

Using county names you can create maps that look like the following. This one took a lot of data wrangling and used the maps (Brownrigg 2021) package, but the output looks nice. The underlying data is identical.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Using R to visualize geographic data

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

library(maps)

library(tidyr)

fips <-

maps::county.fips %>%

as_tibble %>%

extract(polyname,

c("region", "subregion"), "^([^,]+),([^,]+)$")

county_data <-

ggplot2::map_data("county") %>%

left_join(fips) %>%

mutate(county = paste(region,subregion, sep = ','))

customers <- left_join(customers,county_data, by = 'county')

counts <- customers %>% group_by(county) %>%

summarise(accounts = n())

county_data <- county_data %>% left_join(counts,by='county')

state_data <- map_data("state")

main_color <- 'steelblue4'

county_data$accounts <- ifelse(is.na(county_data$accounts) == T,

1,

county_data$accounts)

# adjust number of accounts per county

correction <- county_data %>% select(county,accounts) %>%

group_by(county) %>%

mutate(adjustment = n()) %>%

unique() %>%

summarise(adj_accounts = accounts/adjustment) %>%

select(county,adj_accounts)

correction$adj_accounts <- ifelse(correction$adj_accounts <= 1,

1,

correction$adj_accounts)

county_data <- county_data %>% left_join(correction, by = 'county')

region_map <-

county_data %>%

ggplot(aes(long, lat, group = group)) +

geom_polygon(aes(fill=log10((adj_accounts))),

color=main_color,size = 0) +

geom_polygon(data = state_data ,color="white",

size = .01,fill = 'transparent') +

coord_map(xlim = c(-91,-79), ylim = c(31,38.5)) +

#scale_fill_viridis(option="inferno") +

scale_fill_gradient(low = main_color ,high = 'white') +

labs( x = '', y ='',

title = "Nashville ticket purchasers",

subtitle = "Total accounts by county",

caption = "purchaser density") +

theme(plot.caption = element_text(hjust = 0,

face= "italic",color = "grey90"),

plot.title.position = "plot",

plot.caption.position = "plot",

plot.subtitle = element_text(color = "grey90")) +

graphics_theme_1 +

theme(rect = element_rect(fill = main_color ),

axis.text.x = element_blank(),

axis.text.y = element_blank(),

panel.grid.major = element_line(colour = main_color ),

panel.grid.minor = element_line(colour = main_color ),

panel.background = element_rect(fill = main_color ,

colour = main_color ),

plot.background = element_rect(fill = main_color ,

colour = main_color ),

legend.position="none")

7.2.1.3 Model the data

While we will use the mlr3 framework here, it is essential to understand that there is no need to use one of these frameworks. You can call functions directly. mlr3 descends from mlr, (Bischl et al. 2021) but is built on a more modern framework. You’ll want to begin by downloading the library and poking around in it 70.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Download and install the mlr3 libraries

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

library("mlr3") # install.packages("mlr3viz")

library("mlr3learners") # install.packages("mlr3learners")

library("mlr3viz") # install.packages("mlr3viz")

library("mlr3tuning") # install.packages("mlr3tuning")

library("paradox") # install.packages("paradox")After downloading some of the packages that we will need, we can go ahead and get started on the task of modeling the data. We want to determine how likely a specific season ticket holder will renew. Make sure that your data set doesn’t contain any characters. You’ll need to dummy code or change them to factors.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Recode response to a factor

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

mod_data_numeric$renewed <- factor(mod_data_numeric$renewed)This is a classification problem, and mlr3 follows a specific pattern when building a model. The data is placed in an object called a task:

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Build task

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

task_mod_data <- TaskClassif$new(id = "task_renew",

backend = mod_data_numeric,

target = "renewed",

positive = "r")

# Add a task to the task dictionary

mlr_tasks$add("task_renew", task_mod_data)The input here is straightforward. We name the object, tell it what data to use, give it a target column, and a result. In this case, “r” indicates that the account was renewed in the past.

After you have a task, you will want to select the learner you wish to use. MLR works with several other libraries. In this case, I would like to apply a random forest to this data and use the ranger (Wright, Wager, and Probst 2022) package. Ranger is a powerful library that includes lots of tools you can leverage to build random forest models. You can add parameters from the ranger function to the library in the following code chunk.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Define learner

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

learner_ranger_rf <- lrn("classif.ranger",

predict_type = "prob",

mtry = 3,

num.trees = 500)

# Check parameters with this: learner_ranger_rf$param_set$ids()

# look at a list of learners: mlr3::mlr_learnersWe can now build a test and training data set. As a reminder, we could also use a three-way data partition to have a calibration data set. However, this is optional. We’ll see a better way to do this in a following chapter.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Build test and training data set

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

set.seed(44)

train_mod_data <- sample(task_mod_data$nrow,

0.75 * task_mod_data$nrow)

test_mod_data <- setdiff(seq_len(task_mod_data$nrow),

train_mod_data)Training the model is simple. First, we’ll use our learner object and point it to our task with rows identified with our training data set.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Train the model

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

learner_ranger_rf$train(task = task_mod_data,

row_ids = train_mod_data)The learner contains several valuable pieces of data that were generated. You can access them in a few different ways.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Inspect the results

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# print(learner_ranger_rf$model)

learner_output <-

tibble::tibble(

numTrees = unname(learner_ranger_rf$model$num.trees),

trys = unname(learner_ranger_rf$model$mtry),

samples = unname(learner_ranger_rf$model$num.samples),

error = unname(learner_ranger_rf$model$prediction.error)

)| numTrees | trys | samples | error |

|---|---|---|---|

| 500 | 3 | 10279 | 0.1391261 |

This model doesn’t do a great job judging by the prediction error. Let’s take a look at it on our holdout sample:

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Evaluate holdout sample

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

prediction <- learner_ranger_rf$predict(task_mod_data,

row_ids = test_mod_data)There are several ways to consider this model’s accuracy, and interpretation can be confusing. The first thing to look at is a confusion matrix. A confusion matrix is a simple way to gauge how well your model predictions performed against known values.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Confusion matrix

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

prediction$confusion

#> truth

#> response r nr

#> r 2662 508

#> nr 106 151A confusion matrix demonstrates how often the model was correct and incorrect for each response. In this case, our model could be performing better. Would it serve better than a random guess? There are many other metrics that you can extract from your model.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Evaluate holdout sample

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

measure = msr("classif.acc")

prediction$score(measure)

#> classif.acc

#> 0.8208345In this case, our model is 0.8208345 percent accurate. But, first, let’s visualize some of the results.

For simple models, the mlr3::autoplot() function includes several graphs and is built on ggplot2, which means you can apply your themes to them. But first, let’s explore our data a little more. You can access the predictions with this command learner_ranger_rf\(model\)predictions. The probabilities may be helpful depending on what you are doing.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Access model predictions

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

probs <- as.data.frame(learner_ranger_rf$model$predictions)

head(probs)

#> r nr

#> 1 0.5376683 0.46233166

#> 2 0.9015481 0.09845190

#> 3 0.9252880 0.07471201

#> 4 0.9603436 0.03965638

#> 5 0.9370835 0.06291653

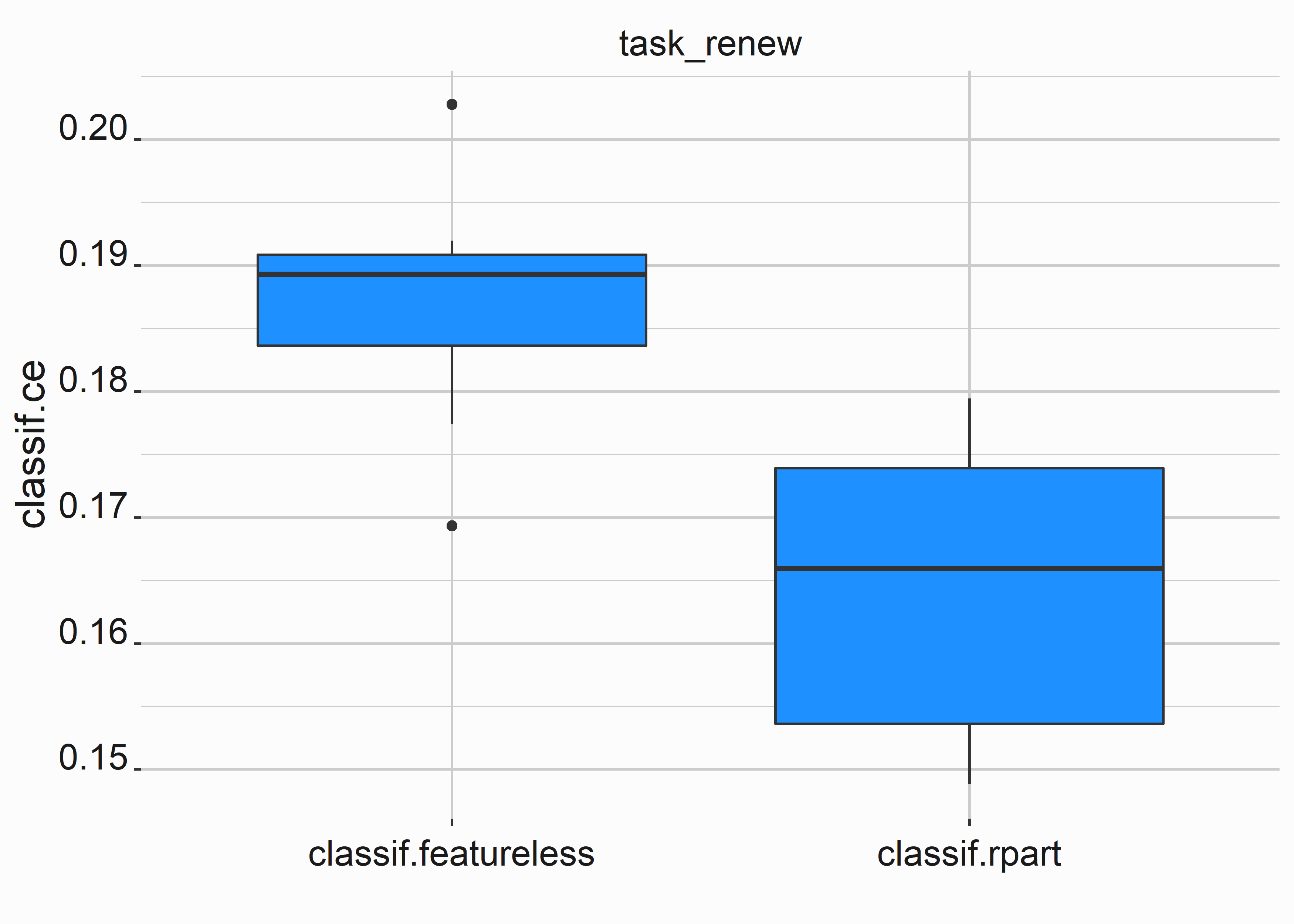

#> 6 0.9028345 0.09716551We can compare models against one another in a couple of different ways. Here we will compare our random forest model to a model that predicts the classifier. It doesn’t use the parameters we fed to our model.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Evaluate holdout sample

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

tasks <- tsks(c("task_renew"))

learner <- lrns(c("classif.featureless","classif.rpart"),

predict_type = "prob")

resampling <- rsmps("cv")

object <- benchmark(benchmark_grid(tasks,

learner,

resampling))

# Use head(fortify(object)) to see the ce for the resamplesOur classification error is better with our random forest, but not by a significant amount. These classification errors are from resampling and rerunning the models.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Boxplot of classification error

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

bplot <-

autoplot(object) +

graphics_theme_1 +

geom_boxplot(fill = 'dodgerblue')

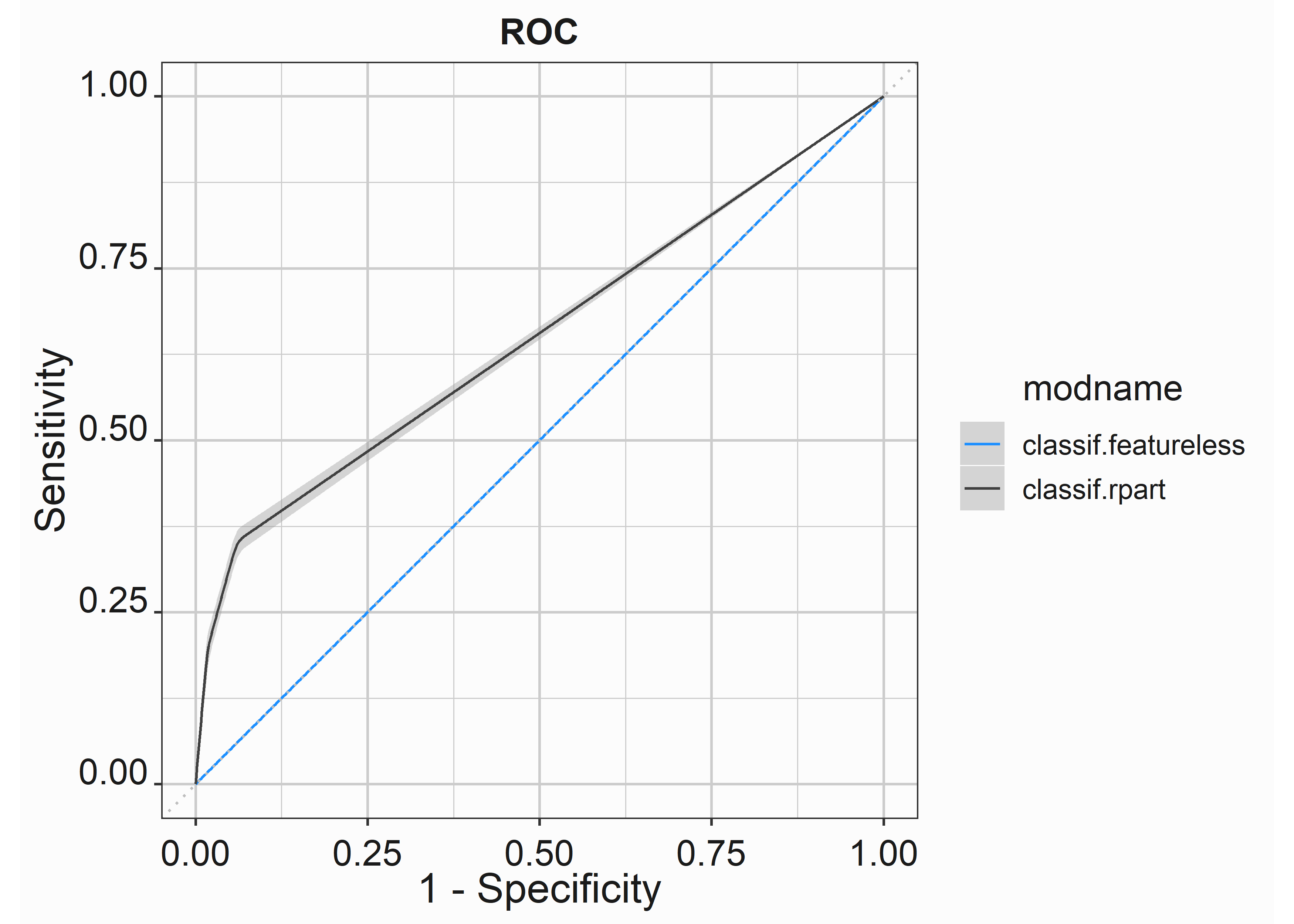

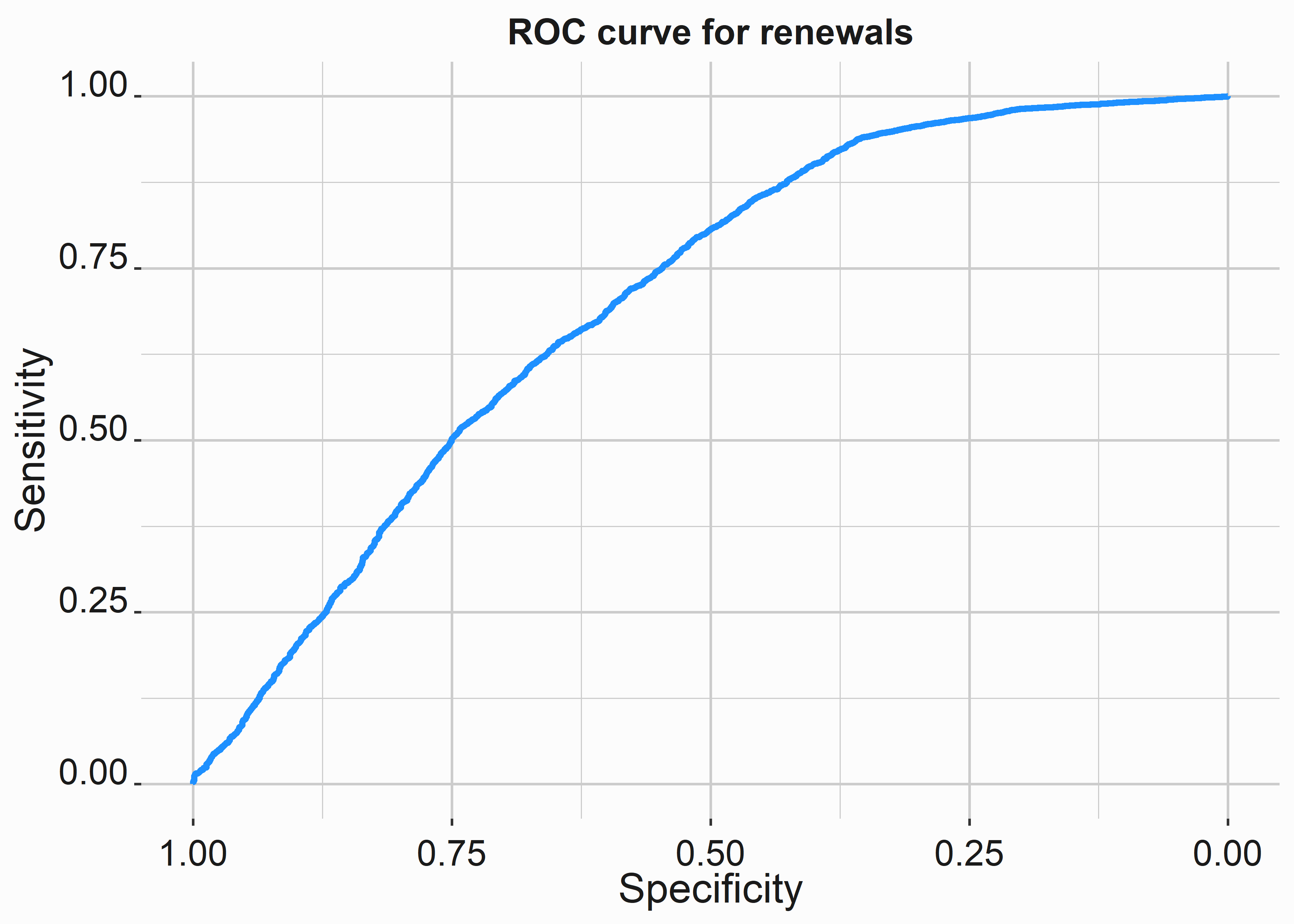

We can also see that we generate some lift with the model by looking at the ROC curve.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# ROC curve for random forest model

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

roc_model <-

autoplot(object$filter(task_ids = "task_renew"),

type = "roc") +

graphics_theme_1 +

scale_color_manual(values = palette)

So what do we do with this data? We can now use our model to predict how likely a person is to renew their ticket. However, we can see that the model doesn’t perform as well as we would like. We have a few options in terms of proceeding:

- Tune the model parameters to try to improve it

- Try a different model

- Get more data

Let’s try a couple of different models and attempt to tune the models to improve their accuracy.

7.2.1.3.1 Resampling

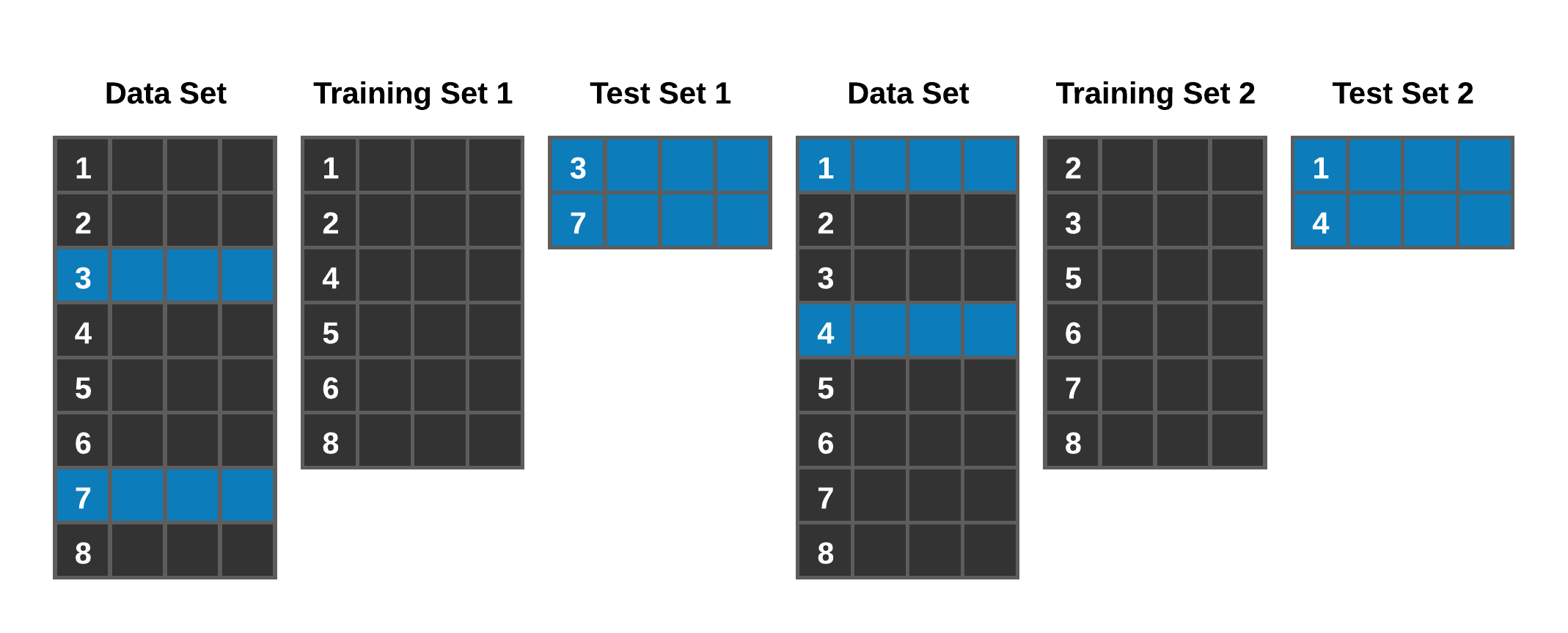

Conceptually, our last model was validated on one training set of data and one test set of data. Occasionally you’ll see a three-way partition of data such as train, test, and calibration set, but often it is just a train and test set randomly sampled from the entire data set. In many cases, this is OK, but it could give you more confidence in your model than warranted. Resampling strategies will help to calibrate your model and give you more confidence in its accuracy. We can visualize what we mean by resampling in figure 7.1.

Figure 7.1: Resampling concept

A standard method you will find is 10-fold cross-validation. The learning procedure is executed ten times on different training sets (that overlap), and the ten error estimates are averaged to yield an overall error estimate (Ian H. Witten 2011). Leveraging a framework such as mlr3 makes these efforts (resampling and tuning) much more manageable. Let’s look at an example of cross-validation regarding our already constructed model.

The task and learner objects are identical to what we saw in the previous sections.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Rebuild model

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

task_mod_data <- TaskClassif$new(id = "task_renew",

backend = mod_data_numeric,

target = "renewed",

positive = "r")

learner_ranger_rf$train(task_mod_data, row_ids = train_mod_data)However, we will need to add a resampling object:

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Add a resampling parameter

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

resampling_mod_data <- rsmp("cv")We’ll then need to instantiate the resampling strategy. This means that we are going to create it again.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Rebuild model

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

resampling_mod_data$instantiate(task_mod_data)

resampling_mod_data$iters

#> [1] 10We can now call the resample. This will take longer than we have seen because we are building a model on multiple data sets.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# We can now call the resample object

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

resamp <- resample(task_mod_data,

learner_ranger_rf,

resampling_mod_data,

store_models = TRUE)

#> INFO [09:56:34.816] [mlr3] Applying learner 'classif.ranger' on task 'task_renew' (iter 1/10)

#> INFO [09:56:38.699] [mlr3] Applying learner 'classif.ranger' on task 'task_renew' (iter 2/10)

#> INFO [09:56:42.644] [mlr3] Applying learner 'classif.ranger' on task 'task_renew' (iter 3/10)

#> INFO [09:56:46.535] [mlr3] Applying learner 'classif.ranger' on task 'task_renew' (iter 4/10)

#> INFO [09:56:50.122] [mlr3] Applying learner 'classif.ranger' on task 'task_renew' (iter 5/10)

#> INFO [09:56:54.030] [mlr3] Applying learner 'classif.ranger' on task 'task_renew' (iter 6/10)

#> INFO [09:56:58.063] [mlr3] Applying learner 'classif.ranger' on task 'task_renew' (iter 7/10)

#> INFO [09:57:01.543] [mlr3] Applying learner 'classif.ranger' on task 'task_renew' (iter 8/10)

#> INFO [09:57:05.144] [mlr3] Applying learner 'classif.ranger' on task 'task_renew' (iter 9/10)

#> INFO [09:57:09.051] [mlr3] Applying learner 'classif.ranger' on task 'task_renew' (iter 10/10)You now have a more sure way to evaluate your model.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Rebuild model

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

resamp$aggregate(msr("classif.ce"))

#> classif.ce

#> 0.1794095

# Look at scores from the models: resamp$score(msr("classif.ce"))Our classification error has improved. That is great! How do we improve further?

7.2.1.3.2 Optimizing your model

Many algorithms have parameters that can alter the performance of the model. For instance, a random forest can have different numbers of trees applied to the model. So how are you tuning the algorithm appropriately?

Let’s look at the different parameters available to the ranger package. There are 29, but we will only look at the first few.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Parameter set

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

param_set <- as.data.frame(learner_ranger_rf$param_set$ids())

head(param_set)

#> learner_ranger_rf$param_set$ids()

#> 1 alpha

#> 2 always.split.variables

#> 3 class.weights

#> 4 holdout

#> 5 importance

#> 6 keep.inbagLet’s select a couple of parameters to tune

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Tuning parameters

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

tune_rf_params <- ParamSet$new(list(

ParamInt$new("min.node.size", lower = 10, upper = 200),

ParamInt$new("max.depth", lower = 2, upper = 20),

ParamInt$new("num.trees", lower = 500, upper = 600)

))We will also have to consider a resampling strategy. Since cross-validated results demonstrated similar error rates, let’s use a holdout sample. Again, we’ll use classification error as our measure.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# set resampling and eval parameters

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

resamp_strat <- rsmp("holdout")

measure_mod_data <- msr("classif.ce")

evals_10 <- trm("evals", n_evals = 10)Let’s combine everything into a tune instance that will pass our new criteria to the model.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Build a tuning instance

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

tune_instance <- TuningInstanceSingleCrit$new(

task = task_mod_data,

learner = learner_ranger_rf,

resampling = resamp_strat,

measure = measure_mod_data,

search_space = tune_rf_params,

terminator = evals_10

)Now we have to determine how we search for different parameters to search. First, we’ll use a random search. A random search means that levels will be randomly searched within our set parameters.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Randomly select options within tuning min and max

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

tuner_rf = tnr("random_search")

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Run the models

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

tuner <- tuner_rf$optimize(tune_instance)

#> INFO [09:57:24.054] [bbotk] Starting to optimize 3 parameter(s) with '<OptimizerRandomSearch>' and '<TerminatorEvals> [n_evals=10, k=0]'

#> INFO [09:57:24.068] [bbotk] Evaluating 1 configuration(s)

#> INFO [09:57:24.104] [mlr3] Running benchmark with 1 resampling iterations

#> INFO [09:57:24.109] [mlr3] Applying learner 'classif.ranger' on task 'task_renew' (iter 1/1)

#> INFO [09:57:26.038] [mlr3] Finished benchmark

#> INFO [09:57:26.161] [bbotk] Result of batch 1:

#> INFO [09:57:26.163] [bbotk] min.node.size max.depth num.trees classif.ce warnings

#> INFO [09:57:26.163] [bbotk] 123 18 542 0.175093 0

#> INFO [09:57:26.163] [bbotk] errors runtime_learners

#> INFO [09:57:26.163] [bbotk] 0 1.91

#> INFO [09:57:26.163] [bbotk] uhash

#> INFO [09:57:26.163] [bbotk] 05488eaa-eeb9-44a2-bba5-5cf18aaa84f7

#> INFO [09:57:26.166] [bbotk] Evaluating 1 configuration(s)

#> INFO [09:57:26.183] [mlr3] Running benchmark with 1 resampling iterations

#> INFO [09:57:26.188] [mlr3] Applying learner 'classif.ranger' on task 'task_renew' (iter 1/1)

#> INFO [09:57:27.848] [mlr3] Finished benchmark

#> INFO [09:57:27.869] [bbotk] Result of batch 2:

#> INFO [09:57:27.871] [bbotk] min.node.size max.depth num.trees classif.ce warnings

#> INFO [09:57:27.871] [bbotk] 200 17 507 0.1726855 0

#> INFO [09:57:27.871] [bbotk] errors runtime_learners

#> INFO [09:57:27.871] [bbotk] 0 1.64

#> INFO [09:57:27.871] [bbotk] uhash

#> INFO [09:57:27.871] [bbotk] c6a73688-fec4-4a27-a4a7-97385e8e7fa4

#> INFO [09:57:27.873] [bbotk] Evaluating 1 configuration(s)

#> INFO [09:57:27.890] [mlr3] Running benchmark with 1 resampling iterations

#> INFO [09:57:27.894] [mlr3] Applying learner 'classif.ranger' on task 'task_renew' (iter 1/1)

#> INFO [09:57:29.308] [mlr3] Finished benchmark

#> INFO [09:57:29.326] [bbotk] Result of batch 3:

#> INFO [09:57:29.327] [bbotk] min.node.size max.depth num.trees classif.ce warnings

#> INFO [09:57:29.327] [bbotk] 120 11 508 0.1739987 0

#> INFO [09:57:29.327] [bbotk] errors runtime_learners

#> INFO [09:57:29.327] [bbotk] 0 1.41

#> INFO [09:57:29.327] [bbotk] uhash

#> INFO [09:57:29.327] [bbotk] ab2b1a52-511b-4d1f-b843-e15848fe8860

#> INFO [09:57:29.330] [bbotk] Evaluating 1 configuration(s)

#> INFO [09:57:29.346] [mlr3] Running benchmark with 1 resampling iterations

#> INFO [09:57:29.350] [mlr3] Applying learner 'classif.ranger' on task 'task_renew' (iter 1/1)

#> INFO [09:57:31.086] [mlr3] Finished benchmark

#> INFO [09:57:31.108] [bbotk] Result of batch 4:

#> INFO [09:57:31.109] [bbotk] min.node.size max.depth num.trees classif.ce warnings

#> INFO [09:57:31.109] [bbotk] 79 11 520 0.1755308 0

#> INFO [09:57:31.109] [bbotk] errors runtime_learners

#> INFO [09:57:31.109] [bbotk] 0 1.73

#> INFO [09:57:31.109] [bbotk] uhash

#> INFO [09:57:31.109] [bbotk] 133dbdb2-5f14-4c09-9761-d1c3d3e845d3

#> INFO [09:57:31.112] [bbotk] Evaluating 1 configuration(s)

#> INFO [09:57:31.131] [mlr3] Running benchmark with 1 resampling iterations

#> INFO [09:57:31.135] [mlr3] Applying learner 'classif.ranger' on task 'task_renew' (iter 1/1)

#> INFO [09:57:33.018] [mlr3] Finished benchmark

#> INFO [09:57:33.039] [bbotk] Result of batch 5:

#> INFO [09:57:33.040] [bbotk] min.node.size max.depth num.trees classif.ce warnings

#> INFO [09:57:33.040] [bbotk] 125 11 594 0.1739987 0

#> INFO [09:57:33.040] [bbotk] errors runtime_learners

#> INFO [09:57:33.040] [bbotk] 0 1.86

#> INFO [09:57:33.040] [bbotk] uhash

#> INFO [09:57:33.040] [bbotk] b740795f-538f-4751-b113-0520fc6cac11

#> INFO [09:57:33.043] [bbotk] Evaluating 1 configuration(s)

#> INFO [09:57:33.059] [mlr3] Running benchmark with 1 resampling iterations

#> INFO [09:57:34.251] [mlr3] Applying learner 'classif.ranger' on task 'task_renew' (iter 1/1)

#> INFO [09:57:36.513] [mlr3] Finished benchmark

#> INFO [09:57:36.543] [bbotk] Result of batch 6:

#> INFO [09:57:36.544] [bbotk] min.node.size max.depth num.trees classif.ce warnings

#> INFO [09:57:36.544] [bbotk] 109 16 597 0.1748742 0

#> INFO [09:57:36.544] [bbotk] errors runtime_learners

#> INFO [09:57:36.544] [bbotk] 0 2.25

#> INFO [09:57:36.544] [bbotk] uhash

#> INFO [09:57:36.544] [bbotk] 0b7811b3-168d-4b93-8584-ef65cbfeeb32

#> INFO [09:57:36.547] [bbotk] Evaluating 1 configuration(s)

#> INFO [09:57:36.566] [mlr3] Running benchmark with 1 resampling iterations

#> INFO [09:57:36.570] [mlr3] Applying learner 'classif.ranger' on task 'task_renew' (iter 1/1)

#> INFO [09:57:37.508] [mlr3] Finished benchmark

#> INFO [09:57:37.534] [bbotk] Result of batch 7:

#> INFO [09:57:37.535] [bbotk] min.node.size max.depth num.trees classif.ce warnings

#> INFO [09:57:37.535] [bbotk] 124 4 580 0.1696214 0

#> INFO [09:57:37.535] [bbotk] errors runtime_learners

#> INFO [09:57:37.535] [bbotk] 0 0.93

#> INFO [09:57:37.535] [bbotk] uhash

#> INFO [09:57:37.535] [bbotk] 2db45362-fab3-4700-81ec-2e9f9fa28bc5

#> INFO [09:57:37.538] [bbotk] Evaluating 1 configuration(s)

#> INFO [09:57:37.555] [mlr3] Running benchmark with 1 resampling iterations

#> INFO [09:57:37.560] [mlr3] Applying learner 'classif.ranger' on task 'task_renew' (iter 1/1)

#> INFO [09:57:40.384] [mlr3] Finished benchmark

#> INFO [09:57:40.407] [bbotk] Result of batch 8:

#> INFO [09:57:40.408] [bbotk] min.node.size max.depth num.trees classif.ce warnings

#> INFO [09:57:40.408] [bbotk] 16 17 560 0.1792515 0

#> INFO [09:57:40.408] [bbotk] errors runtime_learners

#> INFO [09:57:40.408] [bbotk] 0 2.81

#> INFO [09:57:40.408] [bbotk] uhash

#> INFO [09:57:40.408] [bbotk] f3d496b9-5230-4630-a96a-543fe31c3127

#> INFO [09:57:40.410] [bbotk] Evaluating 1 configuration(s)

#> INFO [09:57:40.426] [mlr3] Running benchmark with 1 resampling iterations

#> INFO [09:57:40.430] [mlr3] Applying learner 'classif.ranger' on task 'task_renew' (iter 1/1)

#> INFO [09:57:41.367] [mlr3] Finished benchmark

#> INFO [09:57:41.399] [bbotk] Result of batch 9:

#> INFO [09:57:41.401] [bbotk] min.node.size max.depth num.trees classif.ce warnings

#> INFO [09:57:41.401] [bbotk] 97 5 520 0.1696214 0

#> INFO [09:57:41.401] [bbotk] errors runtime_learners

#> INFO [09:57:41.401] [bbotk] 0 0.94

#> INFO [09:57:41.401] [bbotk] uhash

#> INFO [09:57:41.401] [bbotk] a88c1e71-d8f7-445f-83d5-b60d0da8e850

#> INFO [09:57:41.404] [bbotk] Evaluating 1 configuration(s)

#> INFO [09:57:41.423] [mlr3] Running benchmark with 1 resampling iterations

#> INFO [09:57:41.428] [mlr3] Applying learner 'classif.ranger' on task 'task_renew' (iter 1/1)

#> INFO [09:57:46.447] [mlr3] Finished benchmark

#> INFO [09:57:46.470] [bbotk] Result of batch 10:

#> INFO [09:57:46.471] [bbotk] min.node.size max.depth num.trees classif.ce warnings

#> INFO [09:57:46.471] [bbotk] 42 20 560 0.1772817 0

#> INFO [09:57:46.471] [bbotk] errors runtime_learners

#> INFO [09:57:46.471] [bbotk] 0 5.03

#> INFO [09:57:46.471] [bbotk] uhash

#> INFO [09:57:46.471] [bbotk] 59e4c429-02c2-472b-93a7-01915420499e

#> INFO [09:57:46.478] [bbotk] Finished optimizing after 10 evaluation(s)

#> INFO [09:57:46.478] [bbotk] Result:

#> INFO [09:57:46.479] [bbotk] min.node.size max.depth num.trees learner_param_vals

#> INFO [09:57:46.479] [bbotk] 124 4 580 <list[5]>

#> INFO [09:57:46.479] [bbotk] x_domain classif.ce

#> INFO [09:57:46.479] [bbotk] <list[3]> 0.1696214Now we can take a look at our best result.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Get the best parameters

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

best_params <- tune_instance$result_learner_param_valsThe best results came from a minimum node size of {r tune_instance$result_learner_param_vals$min.node.size and max depth of 4.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Observe new classification error

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

tune_instance$result_y

#> classif.ce

#> 0.1696214Tuning has improved our model. 0.0097881 percent. We can apply this model to our test data and observe the results.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Rerun model

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

learner_ranger_rf$param_set$values =

tune_instance$result_learner_param_vals

learner_ranger_rf$train(task_mod_data)This is where a three-part data partition is useful. We would use it to calibrate these results further. But first, let’s look at how the new predictions look.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Build a tuning instance

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

prediction_tuned <- learner_ranger_rf$predict(task_mod_data,

row_ids = test_mod_data)The new model does a fair job of discriminating between those that renewed and did not renew.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Observe confusion matrix

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

prediction_tuned$confusion

#> truth

#> response r nr

#> r 2714 504

#> nr 54 155

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Observe optimized classification

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

measure = msr("classif.acc")

prediction_tuned$score(measure)

#> classif.acc

#> 0.8371754We certainly improved the accuracy. Now let’s compare our model produced with a random forest to one built with a different algorithm.

7.2.1.4 Comparing the results of different model types

How do we know that the model that we constructed is the best model for our problem? We’ll have to try a few different ones. You will likely have little success with these problems by altering your classification system. We will go through this for demonstration purposes.

We can choose from available learners with the following command. We know that we are looking at classification problems:

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Observe all learners

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

mlr3::mlr_learners

#> <DictionaryLearner> with 27 stored values

#> Keys: classif.cv_glmnet, classif.debug,

#> classif.featureless, classif.glmnet, classif.kknn,

#> classif.lda, classif.log_reg, classif.multinom,

#> classif.naive_bayes, classif.nnet, classif.qda,

#> classif.ranger, classif.rpart, classif.svm,

#> classif.xgboost, regr.cv_glmnet, regr.debug,

#> regr.featureless, regr.glmnet, regr.kknn, regr.km,

#> regr.lm, regr.nnet, regr.ranger, regr.rpart,

#> regr.svm, regr.xgboostMany algorithms will not accept certain data types. Numerical types are always safe. We’ll use the same data set that we have been using to test another algorithm.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Observe all learners

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

task_mod_data_num <- TaskClassif$new(id = "task_bench",

backend = mod_data_numeric,

target = "renewed",

positive = "r")

learner_num <-

list(lrn("classif.xgboost", predict_type = "prob"),

lrn("classif.ranger", predict_type = "prob"))

set.seed(44)

train_mod_data_num <-

sample(task_mod_data_num$nrow, 0.75 * task_mod_data_num$nrow)

test_mod_data_num <-

setdiff(seq_len(task_mod_data_num$nrow), train_mod_data_num)Now we can build a new task consisting of a group of learners. We’ll use a gradient-boosting algorithm, a random forest, and a naive Bayes algorithm.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Build new task and learner

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

design_bnch <- benchmark_grid(

task_bnch <- TaskClassif$new(id = "task_class2",

backend = mod_data_numeric,

target = "renewed",

positive = "r"),

learners_bnch <-

list(lrn("classif.xgboost", predict_type = "prob"),

lrn("classif.ranger", predict_type = "prob"),

lrn("classif.naive_bayes", predict_type = "prob" )),

resamplings_bnch <- rsmp("holdout")

)

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# benchmark our designs

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

bmr = benchmark(design_bnch)

#> INFO [09:57:48.053] [mlr3] Running benchmark with 3 resampling iterations

#> INFO [09:57:48.057] [mlr3] Applying learner 'classif.xgboost' on task 'task_class2' (iter 1/1)

#> INFO [09:57:48.119] [mlr3] Applying learner 'classif.ranger' on task 'task_class2' (iter 1/1)

#> INFO [09:57:53.158] [mlr3] Applying learner 'classif.naive_bayes' on task 'task_class2' (iter 1/1)

#> INFO [09:57:53.586] [mlr3] Finished benchmarkWe can take a look at the available measures with the following command:

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Observe available measures

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

mlr3::mlr_measures

#> <DictionaryMeasure> with 62 stored values

#> Keys: aic, bic, classif.acc, classif.auc,

#> classif.bacc, classif.bbrier, classif.ce,

#> classif.costs, classif.dor, classif.fbeta,

#> classif.fdr, classif.fn, classif.fnr, classif.fomr,

#> classif.fp, classif.fpr, classif.logloss,

#> classif.mauc_au1p, classif.mauc_au1u,

#> classif.mauc_aunp, classif.mauc_aunu,

#> classif.mbrier, classif.mcc, classif.npv,

#> classif.ppv, classif.prauc, classif.precision,

#> classif.recall, classif.sensitivity,

#> classif.specificity, classif.tn, classif.tnr,

#> classif.tp, classif.tpr, debug, oob_error,

#> regr.bias, regr.ktau, regr.mae, regr.mape,

#> regr.maxae, regr.medae, regr.medse, regr.mse,

#> regr.msle, regr.pbias, regr.rae, regr.rmse,

#> regr.rmsle, regr.rrse, regr.rse, regr.rsq,

#> regr.sae, regr.smape, regr.srho, regr.sse,

#> selected_features, sim.jaccard, sim.phi, time_both,

#> time_predict, time_trainWe can view the measures for each algorithm with the following command:

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Compare the models

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

measures = list(

msr("classif.auc", id = "auc"),

msr("classif.ce", id = "ce_train")

)

measure_list <- as.data.frame(bmr$score(measures))

measure_list[,c(6,11,12)]

#> learner_id auc ce_train

#> 1 classif.xgboost 0.6953685 0.1744364

#> 2 classif.ranger 0.6795682 0.1792515

#> 3 classif.naive_bayes 0.6735490 0.2061720Our xgboost model performed slightly better than the random forest. So we should use it instead.

7.2.1.5 Manually calling a logistic regression model

Logistic regression is a form of regression that “builds a linear model based on a transformed target variable.” (Ian H. Witten 2011) This target variable will be 1 or 0. Applied to our problem, will renew or will not renew. Let’s call a basic logistic regression model for fun.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Compare the models

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

mod <- glm(renewed ~ ticketUsage + tenure +

spend + distance,

data = mod_data_numeric,

family = binomial(link = "logit")

)

mod_sum <-

tibble::tibble(

deviance = unlist(summary(mod)$deviance),

null.deviance = unlist(summary(mod)$null.deviance),

aic = unlist(summary(mod)$aic),

df.residual = unlist(summary(mod)$df.residual),

pseudoR2 = 1 - mod$deviance / mod$null.deviance

)| deviance | null.deviance | aic | df.residual | pseudoR2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11746.19 | 13211.17 | 11756.19 | 13701 | 0.1108893 |

This output looks slightly different than the other regression outputs that we have seen. We won’t cover logistic regression here, but I wanted to inform you. It performs well and is a great place to start if you predict two possible outcomes. Additionally, it would be best if you were careful with these models. We estimated a pseudoRSquared, but there are multiple ways to do it. Try the function pscl::pR2(mod) (Zeileis, Kleiber, and Jackman 2008) to see different methods.

7.2.2 Measuring performance

Measuring performance can be complex. The measures themselves can be technical and confusing. If you are using holdout samples, you can ignore many of them to a degree. On the other hand, if you sampled and calibrated correctly, using “ce” or classification error with a visual inspection of the confusion matrix will often be enough. Let’s build a plot of the classification error to give us additional insight into what is happening.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Compare the models

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

calc_rates <- learner_ranger_rf$predict_newdata(mod_data_numeric)

mod_data_numeric$pred <- predict(mod,newdata = mod_data_numeric,

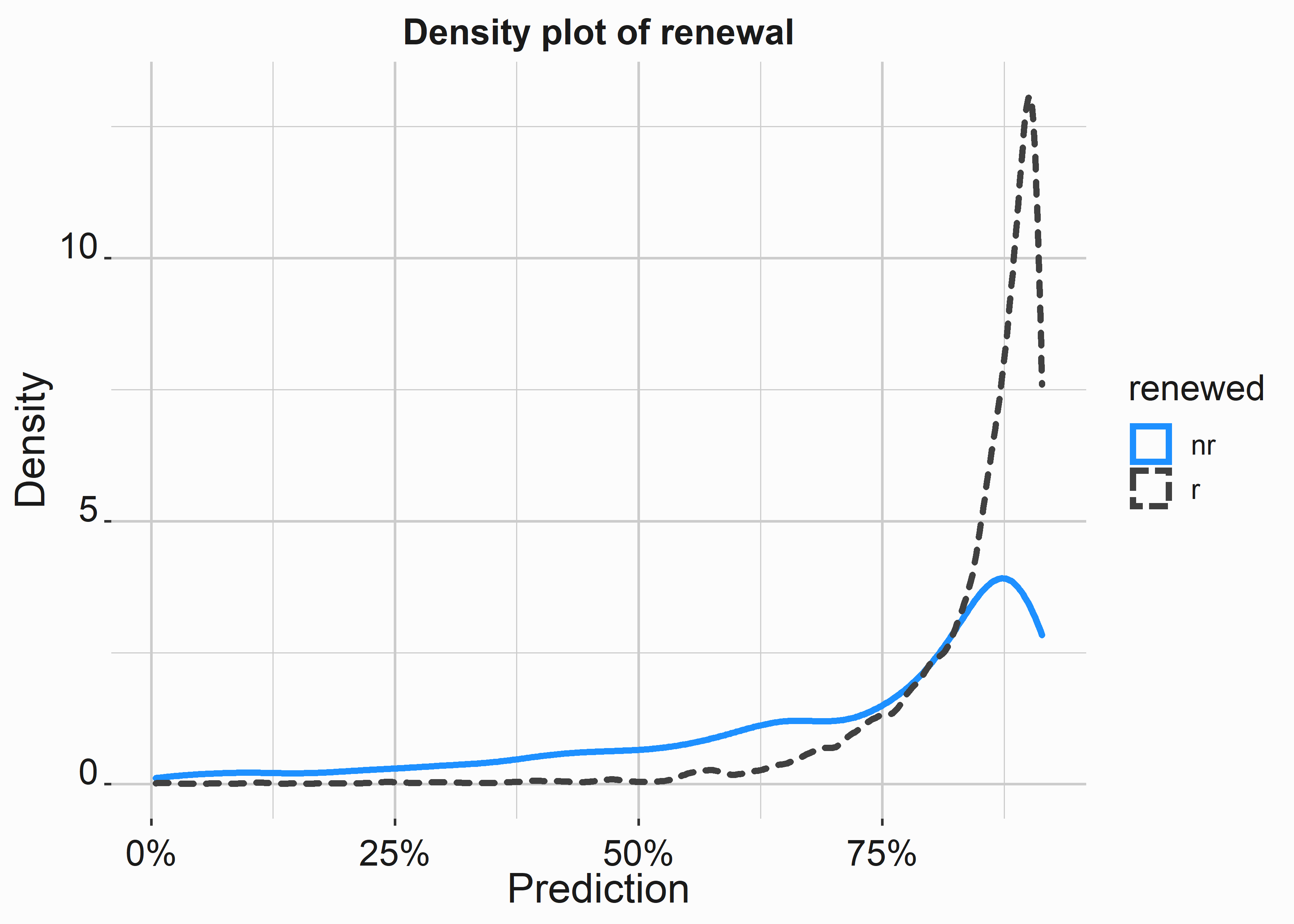

type = 'response')Let’s look at a density plot of the renewal scores and classes.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Density plot of error

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

title <- 'Density plot of renewal'

x_label <- 'Prediction'

y_label <- 'Density'

density_pred <-

ggplot(data = mod_data_numeric,

aes(x=pred,color=renewed,lty=renewed)) +

geom_density(size = 1.2) +

scale_color_manual(values = palette) +

scale_x_continuous(label = scales::percent) +

xlab(x_label) +

ylab(y_label) +

ggtitle(title) +

graphics_theme_1

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# ROC curve

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

library(pROC)

#define object to plot

roc_object <- roc(mod_data_numeric$renewed, mod_data_numeric$pred)

title <- 'ROC curve for renewals'

x_label <- 'Specificity'

y_label <- 'Sensitivity'

roc_graph <-

ggroc(roc_object,colour = 'dodgerblue',size = 1.2) +

xlab(x_label) +

ylab(y_label) +

ggtitle(title) +

graphics_theme_1

Our ROC curve demonstrates that targeting certain groups can be more efficient.

7.3 Using this data

Lead scores are EASY to use. Qualifying leads is the most important analytics exercise that can be quickly and easily deployed. This is thinking strategically at its simplest and finest. First, we need to apply our preferred model to new data. Scored data is typically placed into quantiles and then deployed in order based on what we desire to happen.

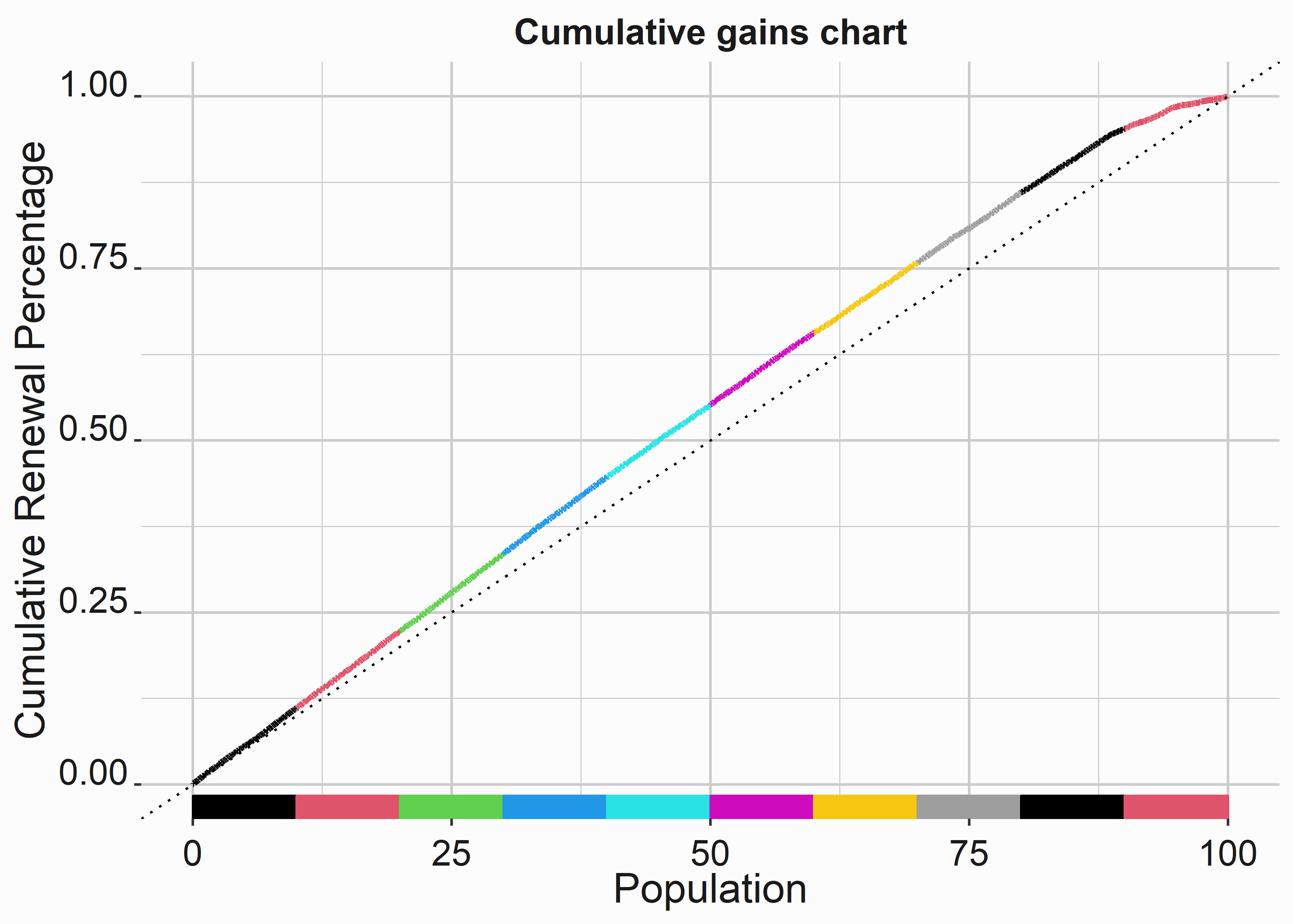

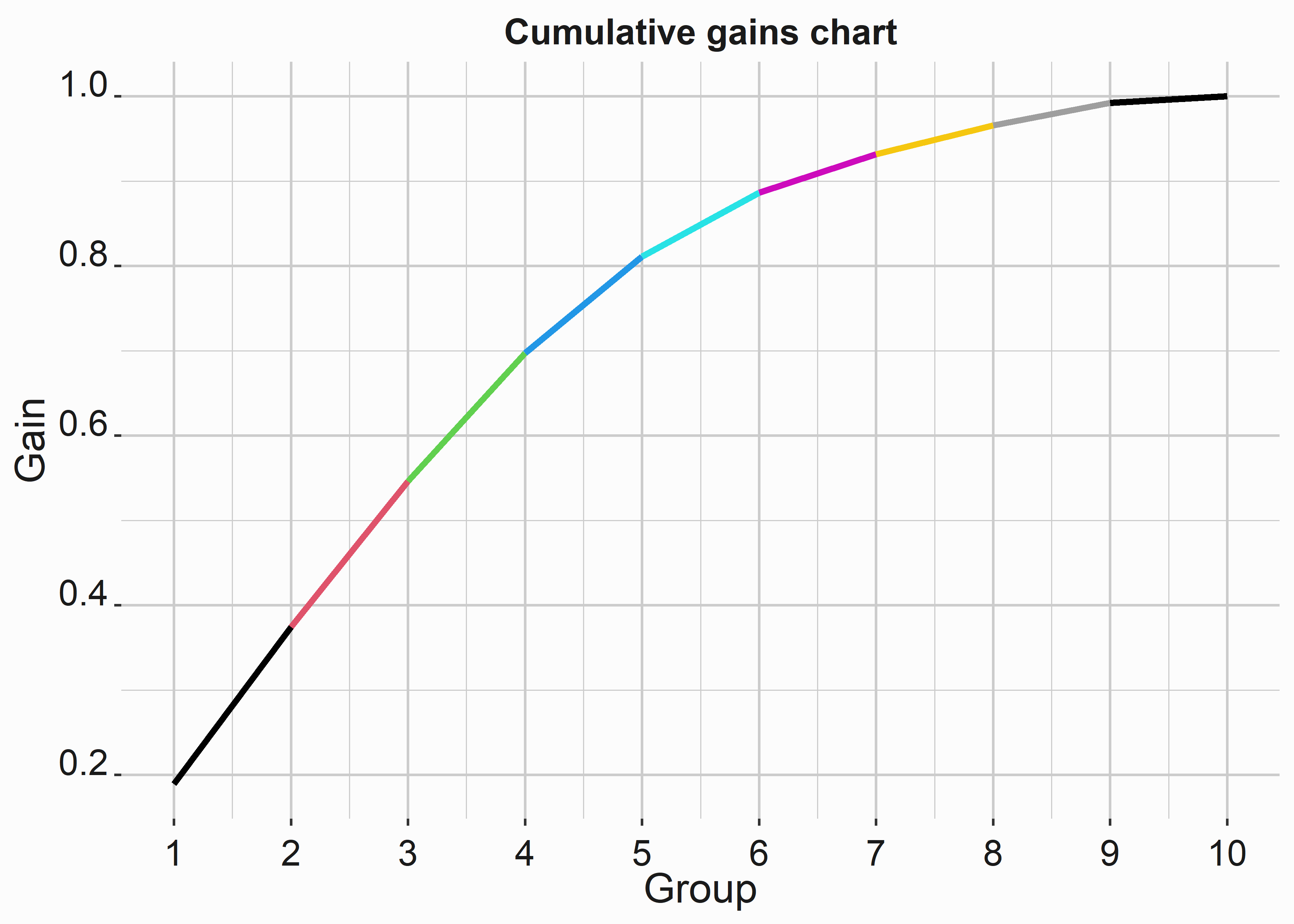

7.3.1 Building cumulative gains charts

How do we know that our model has efficacy in practice? Let’s take a sample of our model data and pretend it is a new group we plan to deploy in a renewal campaign. Let’s begin by borrowing some data from our last analysis. Let’s pretend these individuals are new, and we are trying to renew them.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Build data from cumulative gains chart

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

mod_data_sample <-

mod_data_numeric %>%

dplyr::select(pred,renewed) %>%

dplyr::mutate(custId = seq(1:nrow(mod_data_numeric))) %>%

dplyr::sample_n(5000) %>%

dplyr::arrange(desc(pred))

qt <- quantile(mod_data_sample$pred,

probs = c(.1,.2,.3,.4,.5,.6,.7,.8,.9))

f_apply_quant <- function(x){

ifelse(x >= qt[9],1,

ifelse(x >= qt[8],2,

ifelse(x >= qt[7],3,

ifelse(x >= qt[6],4,

ifelse(x >= qt[5],5,

ifelse(x >= qt[4],6,

ifelse(x >= qt[3],7,

ifelse(x >= qt[2],8,

ifelse(x >= qt[1],9,10)))))))))

}

mod_data_sample$group <- sapply(mod_data_sample$pred,

function(x) f_apply_quant(x))

table(mod_data_sample$group,mod_data_sample$renewed)

#>

#> nr r

#> 1 53 447

#> 2 52 448

#> 3 56 444

#> 4 52 448

#> 5 52 449

#> 6 71 428

#> 7 101 399

#> 8 83 417

#> 9 124 376

#> 10 299 201

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Build data for cumulative gains chart

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

mod_data_sample$renewedNum <-

ifelse(mod_data_sample$renewed == 'r',1,0)

mod_data_sample$perpop <-

(seq(nrow(mod_data_sample))/nrow(mod_data_sample))*100

mod_data_sample$percRenew <-

cumsum(mod_data_sample$renewedNum)/sum(mod_data_sample$renewedNum)

title <- 'Cumulative gains chart'

x_label <- 'Population'

y_label <- 'Cumulative Renewal Percentage'

cgc <-

ggplot(mod_data_sample,aes(y=percRenew,x=perpop)) +

geom_line(color = mod_data_sample$group,size = 1.2 ) +

geom_rug(color = mod_data_sample$group,sides = 'b' ) +

geom_abline(intercept = 0, slope = .01, size = 0.5,lty=3) +

xlab(x_label) +

ylab(y_label) +

ggtitle(title) +

graphics_theme_1

What would this curve look like if the renewal rates differed more by group?

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Build data for improved cumulative gains chart

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

mod_data_gain <- mod_data_sample %>%

group_by(group) %>%

summarise(cumRenewed = sum(renewedNum))

new_renewals <- c(500,490,455,400,300,200,120,90,70,20)

mod_data_gain$cumRenewed <- new_renewals

mod_data_gain$gain <-

cumsum(mod_data_gain$cumRenewed/sum(mod_data_gain$cumRenewed))

title <- 'Cumulative gains chart'

x_label <- 'Group'

y_label <- 'Gain'

cgc_imp <-

ggplot(mod_data_gain,aes(y=gain,x=group)) +

geom_line(color = mod_data_gain$group,size = 1.2) +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = c(0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10)) +

geom_abline(intercept = 0, slope = .01, size = 0.5,lty=3) +

xlab(x_label) +

ylab(y_label) +

ggtitle(title) +

graphics_theme_1

We can see that the curve bulges in the middle. As the curve begins to flatten, your campaign is less efficient. These problems are complex. Your data could be better, and getting the fantastic results you see in texts can be challenging.

7.4 Key concepts and chapter summary

Systematically interacting with your potential customers is a core component of direct marketing. We covered a few primary concepts:

- RFM scores

- Lead scoring with a random forest

- Cross Validation

- Model Optimization

- Model comparisons

- Evaluating your model for efficacy

- How to use these models in practice

These subjects cover some depth of specific techniques for lead scoring and model construction.

- Recency, Frequency, and Monetary Value scores are relatively simple to construct and have been called “poor man’s analytics.” However, they are easy to interpret and simple to use.

- A random forest is a great tool when your data is short-and-wide. The results are easy to interpret and work, as well as logistic regression. This is bread-and-butter machine learning.

- Cross-validating results is an integral part of the analytics process that should be considered when building a model.

- Models can be optimized in different ways depending on the model. This includes regression models and machine learning models.

- You can use readily-available tools to compare models against each other. It is always best to try a couple of different things.

- Leveraging lead scores is simple and makes your salespeople more effective.