3 Data Exploration

R makes it easy to do exploratory work on your data. There are numerous packages and functions that make it simple to visualize and tabulate your data. We’ll leverage many packages outlined in the book “R For Data Science” (Wickham 2017) and our graphics will be created with an excellent graphics package called ggplot2 (Wickham, Chang, et al. 2022). ggplot2 makes it easy to look at data in many different ways.

We’ll also recommend several methods of analyzing your data. “R in Action” by Robert Kabacoff (Kabacoff 2011) does an outstanding job of demonstrating cursory data analysis with a variety of data sets. We’ll reference this book several times in this chapter. While there are innumerable statistical methods and rubrics for analyzing your data, graphs do the best job of conveying most of the information that you will encounter in this book. They are always important and if you don’t like building them analytics may not be for you.

3.1 Building a consistent design language

There are several graphics paradigms available in R and elsewhere. D3 (d3 2020) is an outstanding javascript library for building dynamic graphics. Python also contains several libraries such as seaborn (Waskom 2021) that will help you construct statistical graphics. We’ll use the ggplot2 (Wickham, Chang, et al. 2022) paradigm for the graphics in this book. ggplot2 will make it easy to build consistent and visually appealing graphics in R.

Let’s start by constructing a graphics theme that we will use throughout our examples. We begin this example by creating a color palette that we can use or modify. Afterward, we simply set a variable equal to a set of parameters corresponding to components of the images that we will be creating.

library(ggplot2)

library(dplyr)

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# creating a color palette

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

palette <- c('dodgerblue','grey25','coral','mediumseagreen',

'orchid','firebrick','goldenrod','cyan',

'brown','steelblue','magenta')

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Creating a custom theme

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

graphics_theme_1 <- ggplot2::theme() +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 0, size = 14,

vjust = 0, color = "grey10"),

axis.text.y = element_text(angle = 0, size = 14,

vjust = 0, color = "grey10"),

axis.title.x = element_text(size = 16, face = "plain",

colour = "grey10"),

axis.title.y = element_text(size = 16, face = "plain",

color = "grey10"),

legend.title = element_text(size = 14, face = "plain",

color = "grey10"),

legend.text = element_text(size = 11,

color = "grey10"),

plot.title = element_text(colour = "grey10",

size = 14, angle = 0,

hjust = .5, vjust = .5,

face = "bold"),

legend.position = "right",

legend.background = element_rect(fill = "grey99",

size = 3,

linetype = "solid",

colour = "grey99"),

legend.key = element_rect(fill = "grey99",

color = "grey99"),

strip.background = element_rect(fill = "grey99",

colour = "grey99"),

strip.text = element_text(size = 14,

face = "plain",

color = "grey10"),

panel.grid.major = element_line(colour = "grey80"),

panel.grid.minor = element_line(colour = "grey80"),

panel.background = element_rect(fill = "grey99",

colour = "grey99"),

plot.background = element_rect(fill = "grey99",

colour = "grey99"))The object graphics_theme_1 will be used on all of our subsequent graphs. It will keep them looking consistent. You can easily adjust any element by simply adding it to your plot after the theme. That will override our graphics theme and illustrates some of the elegance of the paradigm. Let’s pull down some data from the FOSBAAS package and take a look at it.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# High level schedule data

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

library(FOSBAAS)

season_data <- FOSBAAS::season_data| gameNumber | team | date | dayOfWeek | month | weekEnd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SF | 2022-03-27 | Sun | Mar | FALSE |

| 2 | SF | 2022-03-28 | Mon | Mar | FALSE |

| 3 | SF | 2022-03-29 | Tue | Mar | FALSE |

| 4 | BAL | 2022-04-05 | Tue | Apr | FALSE |

| 5 | BAL | 2022-04-06 | Wed | Apr | FALSE |

| 6 | BAL | 2022-04-07 | Thu | Apr | FALSE |

We’ve already talked about this data, so the next few sections will demonstrate the sorts of plots and exploratory analysis that you would typically perform to help you understand patterns in the data. If you want to review this data simply type ?FOSBAAS::season_data into your R console. This part of analysis is critical. It helps you understand the data so that you can perform more sophisticated modeling on it in later steps. It is also the best way to communicate patterns in the data to those with less experience with it. I’ll also offer a word of warning. Most people do not think in distributions. Simple bar and line plots will get the most traction with folks. Don’t attempt to explain a box plot to someone in a meeting. You will lose the room.

3.2 Histograms and density plots

Histograms and density plots are critical to understanding the underlying structure of data. Using a point estimate such as an average is a good way to misinterpret data. Learn to think in distributions. When you are at the DMV look at the line of customers and think about their height distribution. When you watch the Olympics think of the distribution of times the athletes ran or swam. Do this everywhere else too. The following two graphs are called with simple commands: geom_histogram and geom_density.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Histograms

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

season_data <- FOSBAAS::season_data

x_label <- ('\n Ticket Sales')

y_label <- ('Count \n')

title <- ('Distribution of Seasonal Ticket Sales')

legend <- ('Season')

hist_sales <-

ggplot2::ggplot(data = season_data,

aes(x = ticketSales,

fill = factor(season))) +

geom_histogram(binwidth = 1000) +

scale_fill_manual(legend, values = palette) +

geom_rug(color = 'coral') +

scale_x_continuous(label = scales::comma) +

scale_y_continuous(label = scales::comma) +

xlab(x_label) +

ylab(y_label) +

ggtitle(title) +

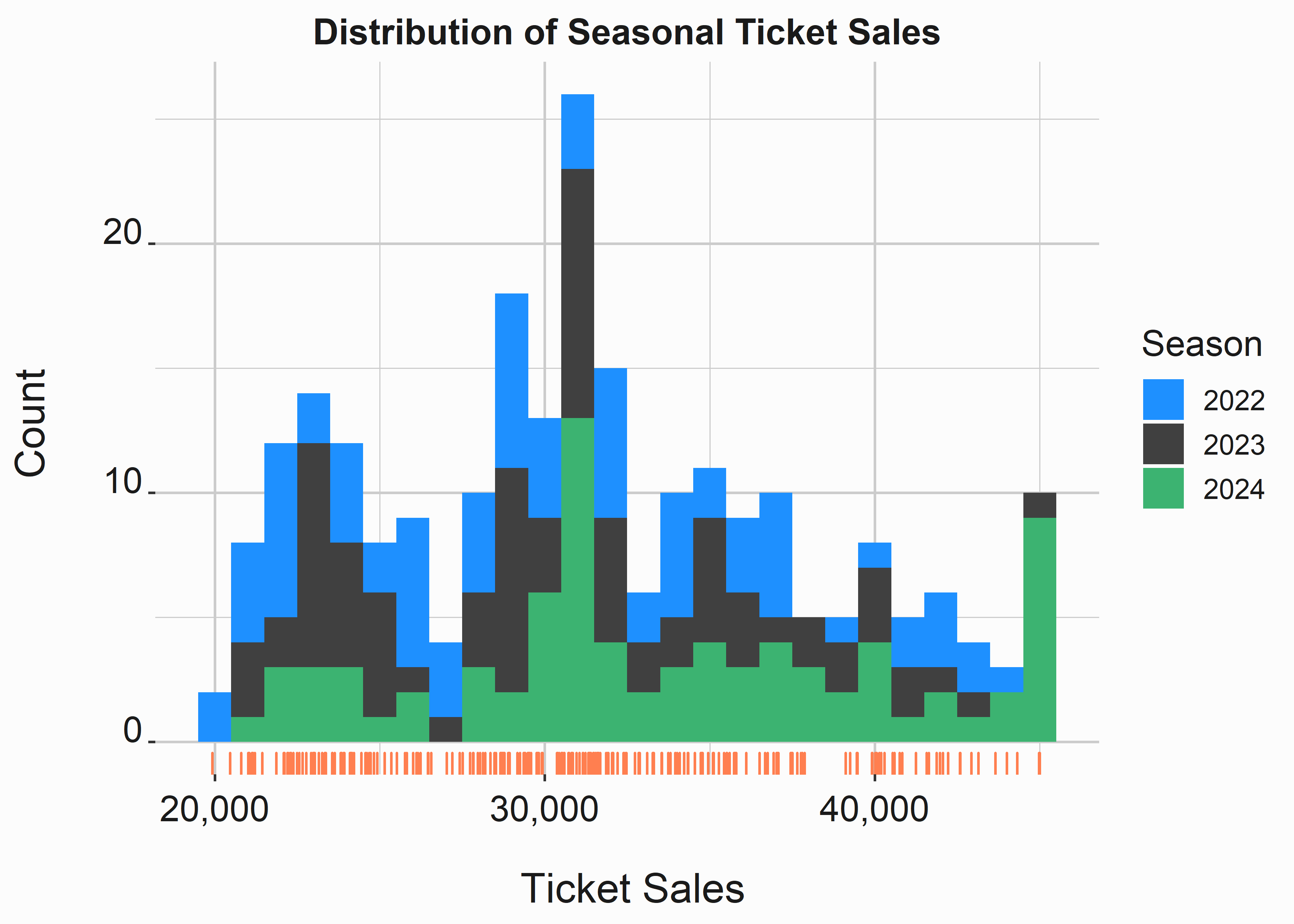

graphics_theme_1This code creates the graph in figure 3.1. Histograms are incredibly useful for understanding a data set’s structure. If you are unfamiliar with them, they demonstrate the count of a specific instance of something (in this case, ticket sales). We also included a rug at the bottom of the graph. This rug demonstrates where the data points actually lie on the graph. It may be unnecessary, but I find that it helps me interpret the graph a little more easily when dealing with smaller data sets. This is especially true for density plots.

The following diagram also layers different seasons on the diagram using colors. The colors that you use are important. While we aren’t going to cover design here, you should have a basic understanding of the color wheel.29 Google it. There are also several R packages that deal with color such as RColorBrewer (Neuwirth 2022). This package was designed for maps and demonstrates the point I am trying to make. Put some thought into the colors that you use and why you use them. It’ll give your graphics a polished and professional look.

Figure 3.1: Histogram of Ticket Sales

How can we interpret this plot? Honestly, it is difficult to see much of a difference. It looks like 2024 had a higher percentage of sellouts. It also looks like there is a huge spike at around 31,000 tickets. Perhaps there are better ways to help us understand this data.

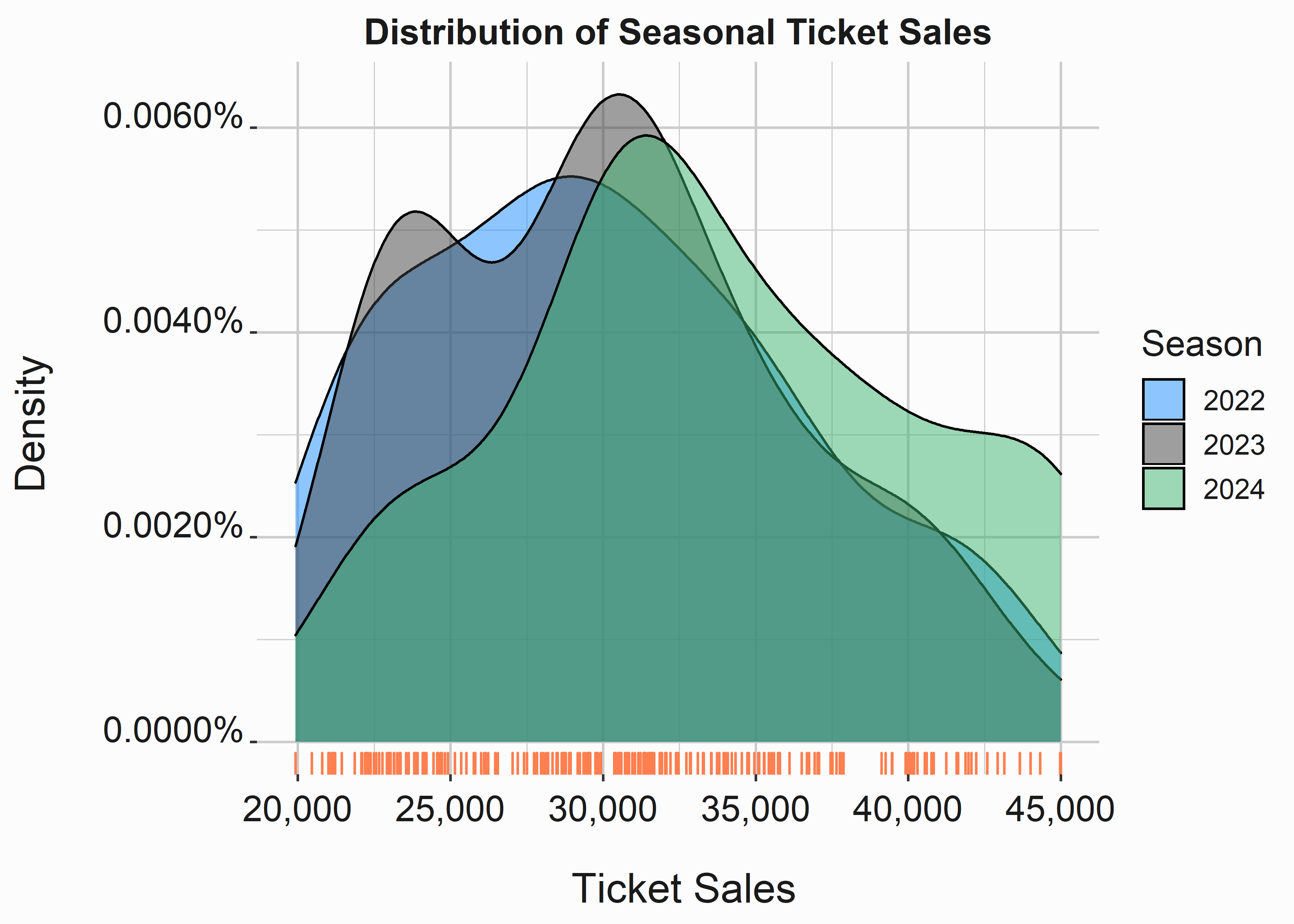

With a small change, you can create a density plot. Density plots convey similar information as histograms, but they can be confusing for some individuals. Know your audience before choosing to use one over a more interpretable histogram. You can see this plot in figure 3.2.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Kernel density plot

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

x_label <- ('\n Ticket Sales')

y_label <- ('Density \n')

title <- ('Distribution of Seasonal Ticket Sales')

legend <- ('Season')

density_sales <-

ggplot2::ggplot(data = season_data,

aes(x = ticketSales,

fill = factor(season))) +

geom_density(alpha = .5) +

scale_fill_manual(legend,values = palette) +

geom_rug(color = 'coral') +

scale_x_continuous(label = scales::comma) +

scale_y_continuous(label = scales::percent) +

xlab(x_label) +

ylab(y_label) +

ggtitle(title) +

graphics_theme_1A kernel density plot represents the density at a particular point. Think of it as how much area lives under the curve. The plot looks like this:

Figure 3.2: Density Plot of Ticket Sales

This graph helps us visualize skew a little better than the histogram. We used an alpha argument to make the graphs transparent. It is much easier to see that 2024 skews to the right more than 2022 or 2023.

How can we interpret the data under curve at a certain point? You can approximate it fairly easily. There are multiple methods to do this and you don’t necessarily have to integrate on the data. However, if you did have to use an integral R can help there too. Keep in mind that if you are actually doing calculus working for a club on the business side you are probably doing something wrong. In fact, if you are using calculus at all you are probably doing something wrong. Take a step back.

You can use the density function to help you understand what is going on with these curves.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Demonstrate AUC

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

den <- density(season_data$ticketSales)

bin_size <- (den$x[2] - den$x[1])

round(sum(den$y) * bin_size,2) # Approximates to 1

#> [1] 1This part should be intuitive. We can now use this data to make observations at specific points on the x axis.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Demonstrate AUC at 40,000 Tickets

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

sum(den$y[den$x >= 40000]) * bin_size

#> [1] 0.1337782About thirteen percent of the area under the curve is at points above 40,000 tickets. We included these calculations for demonstrative purposes. It should make density plots easier to understand. We could perform these calculations for each density curve to help us understand the data in a little more granular fashion.

Histograms and density plots are of particular use when performing certain statistical analyses of data. We’ll use them frequently. Familiarize yourself with them and learn to love them.

3.3 Box, faceted, and scatter plots

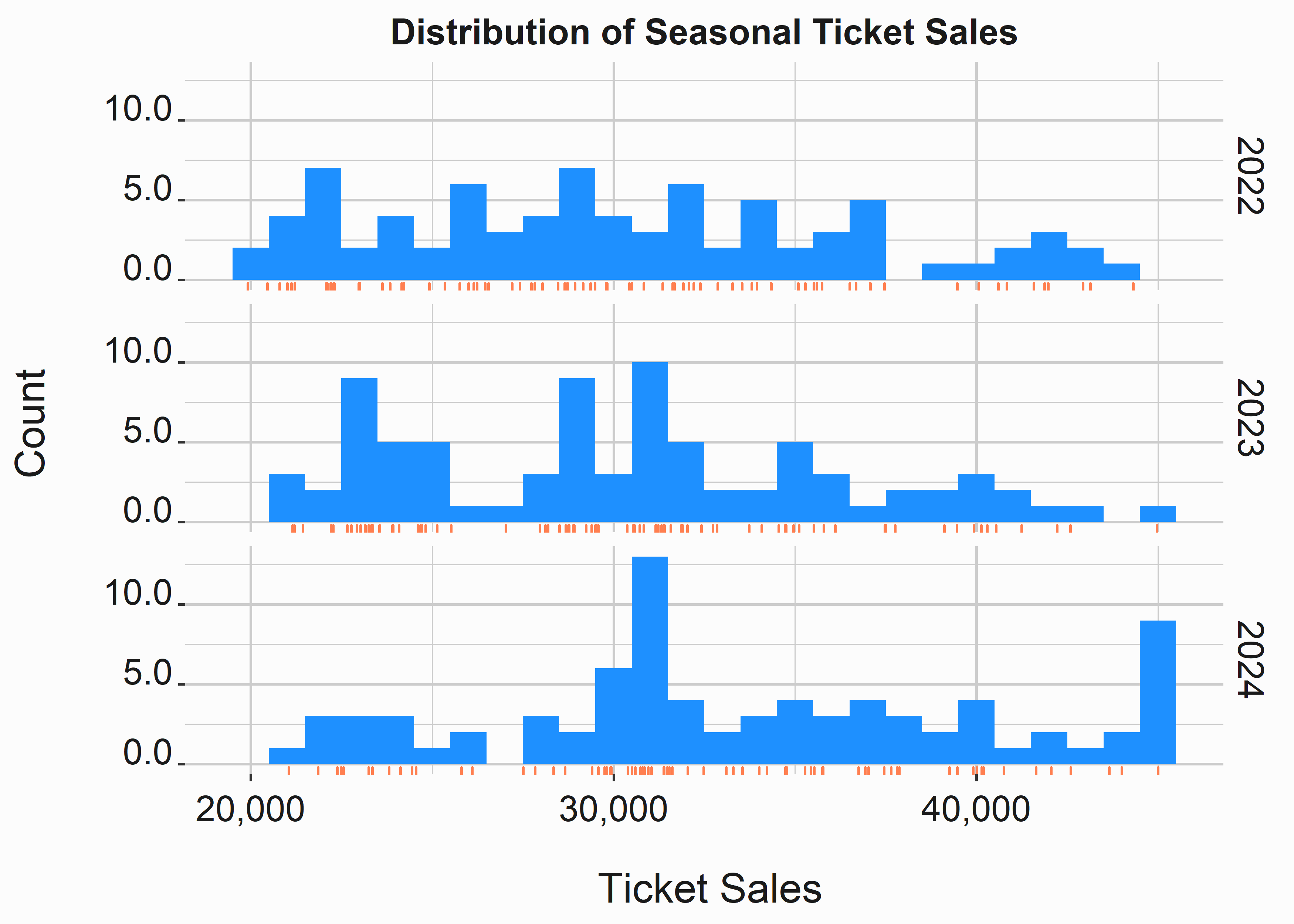

You can also easily split your data by season to analyze the distributions slightly differently. In this case, we’ve used the facet_grid(season ~ .) argument to split the graph on season. There really isn’t anything different here. The function facet_wrap() does something similar. Try it out to see the difference. The faceted histogram can be seen in figure 3.3.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Faceting a plot

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

x_label <- ('\n Ticket Sales')

y_label <- ('Count \n')

title <- ('Distribution of Seasonal Ticket Sales')

histogram_sales_facet <-

ggplot2::ggplot(data = season_data,

aes(x = ticketSales)) +

facet_grid(season ~ .) +

geom_histogram(binwidth = 1000, fill = palette[1]) +

geom_rug(color = 'coral') +

scale_x_continuous(label = scales::comma) +

scale_y_continuous(label = scales::comma) +

xlab(x_label) +

ylab(y_label) +

ggtitle(title) +

graphics_theme_1

Figure 3.3: Faceted histogram

Notice how we restricted the graph to one color. Avoid multiple colors on graphs that split the data. You don’t need to have multiple ways to distinguish individual subsets of the data here. One way will suffice.

We get the same interpretation from this graph as the preceeding one. 2024 is skewed to the right likely indicating higher average ticket sales. 2023 appears to have a few clusters of attendance, while 2022 is fairly evenly distributed. Perhaps this is because of differences in the schedule.

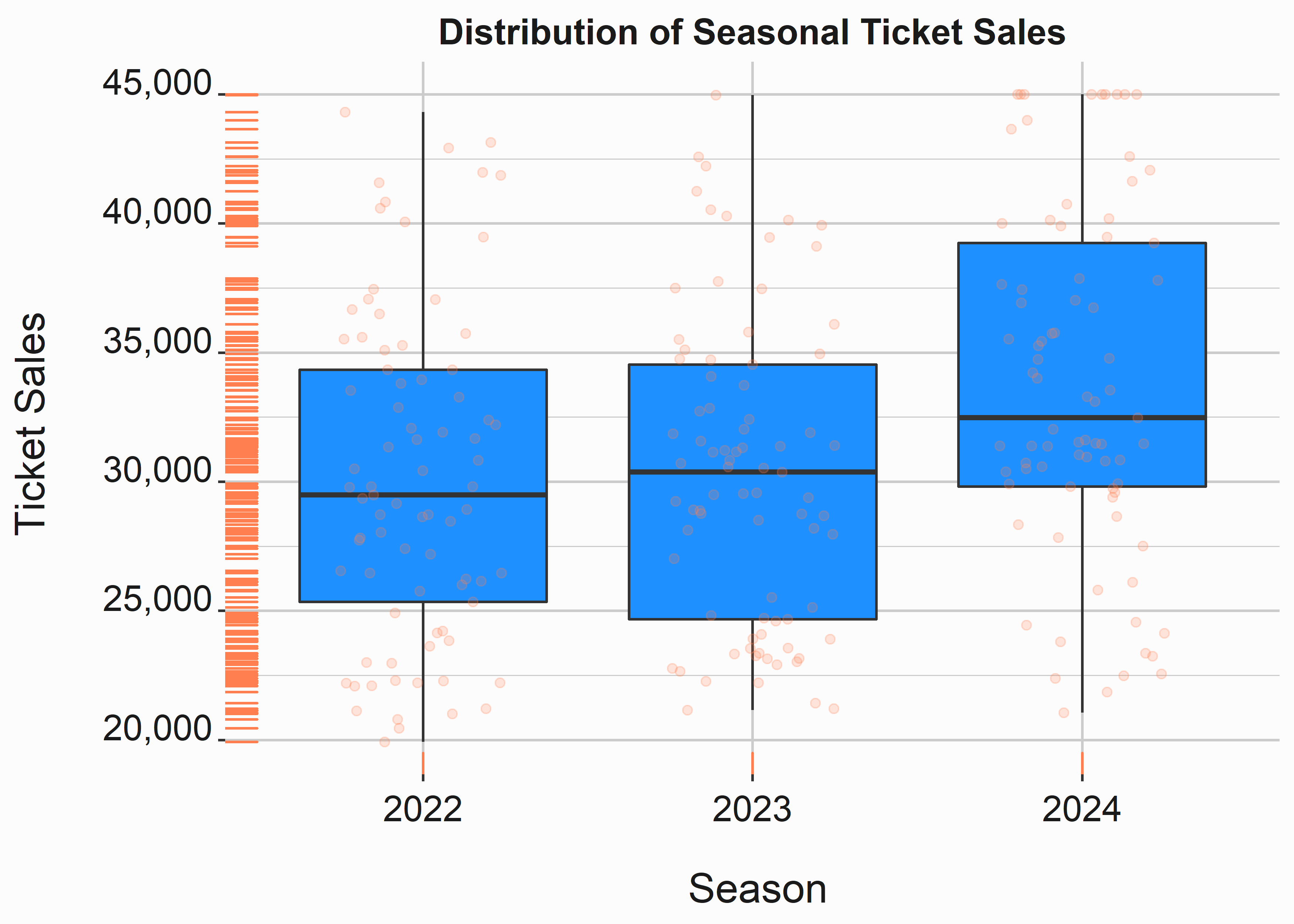

Splitting graphs on various features is very useful and you’ll see it frequently. We can create box-plots by changing one argument. The following code produces the box-plot in figure 3.4.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Box plots

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

x_label <- ('\n Season')

y_label <- ('Ticket Sales \n')

title <- ('Distribution of Seasonal Ticket Sales')

box_sales <-

ggplot2::ggplot(data = season_data,

aes(x = factor(season),

y = ticketSales)) +

geom_boxplot(fill = 'dodgerblue') +

geom_jitter(alpha = .2, height = 0,

width = .25, color = 'coral') +

geom_rug(color = 'coral') +

scale_y_continuous(label = scales::comma) +

xlab(x_label) +

ylab(y_label) +

ggtitle(title) +

graphics_theme_1Boxplots are my preferred method of looking at distributions. In this case, we blended a boxplot with a scatter plot. How do you interpret a boxplot? The black line in the middle of the colored section represents the median. The box represents the 50th percentile of values. This is the interquartile (IQR) range representing the values between 25% and 50%. The whiskers represent a calculation based on that range and dots represent outliers.

Figure 3.4: Segmented histogram and box-whisker plots

This data is easier to interpret in this fashion. The IQR is skewed much higher and we clearly have a larger median value. Why use median instead of the mean? The median is a safer interpretation when you are looking at non-normal distributions (distributions with skew). It is actually best to look at both of them, but we will get to that.

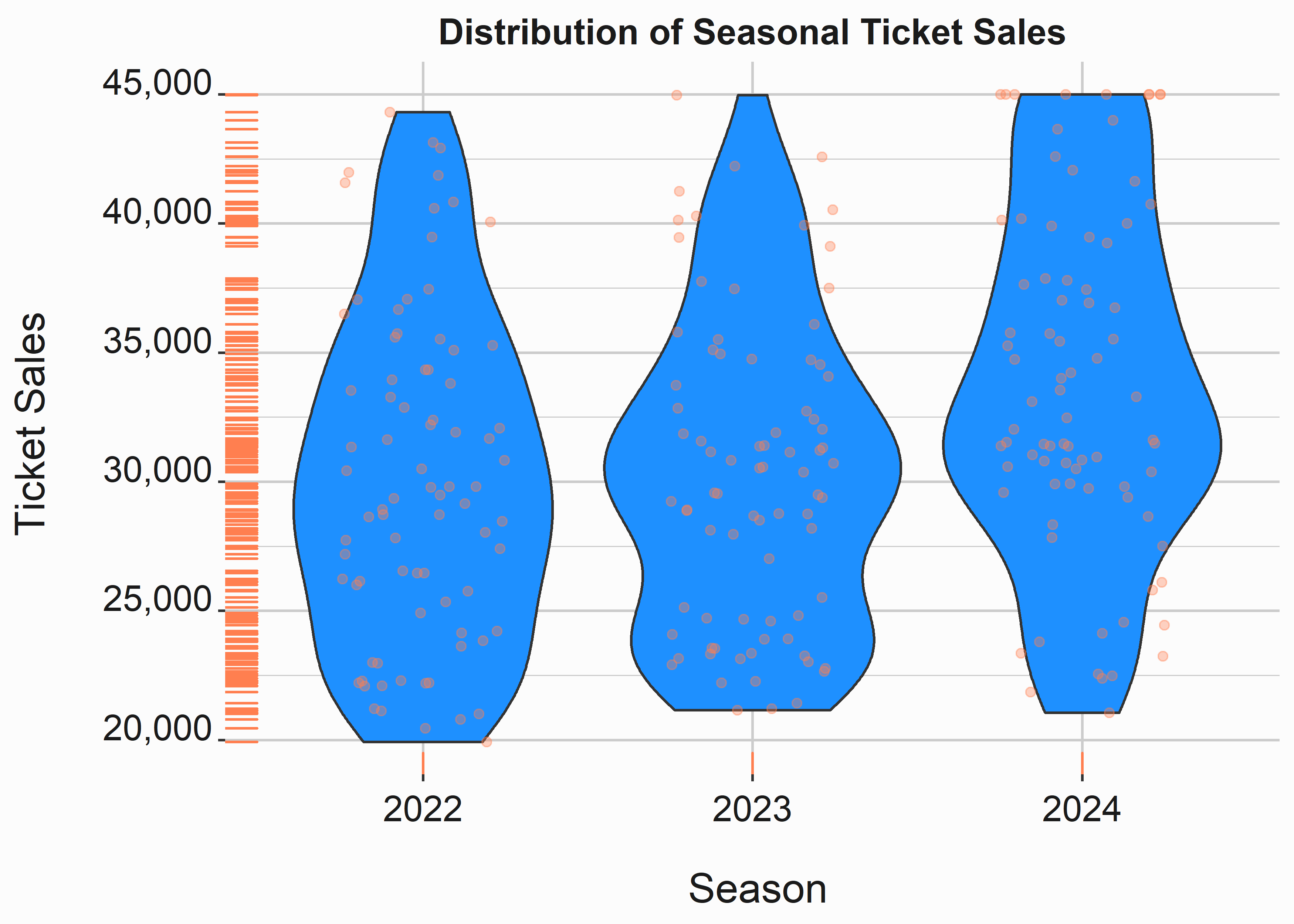

We’ll explore one more type of basic plot. A violin plot will blend a density plot and boxplot. The following code produces the plot in figure 3.5.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# violin plot

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

x_label <- ('\n Season')

y_label <- ('Ticket Sales \n')

title <- ('Distribution of Seasonal Ticket Sales')

violin_sales <-

ggplot2::ggplot(data = season_data,

aes(x = factor(season),

y = ticketSales)) +

geom_violin(fill = 'dodgerblue') +

geom_jitter(alpha = .35, height = 0,

width = .25, color = 'coral') +

geom_rug(color = 'coral') +

scale_y_continuous(label = scales::comma) +

xlab(x_label) +

ylab(y_label) +

ggtitle(title) +

graphics_theme_1

Figure 3.5: Segmented violin plot

I think violin plots are interesting, but I typically don’t use them. I prefer to split my density plots and boxplots into separate graphs. You may feel differently. I would not recommend showing one of these plots to someone with limited statistical experience. Perhaps you shouldn’t use them at all.

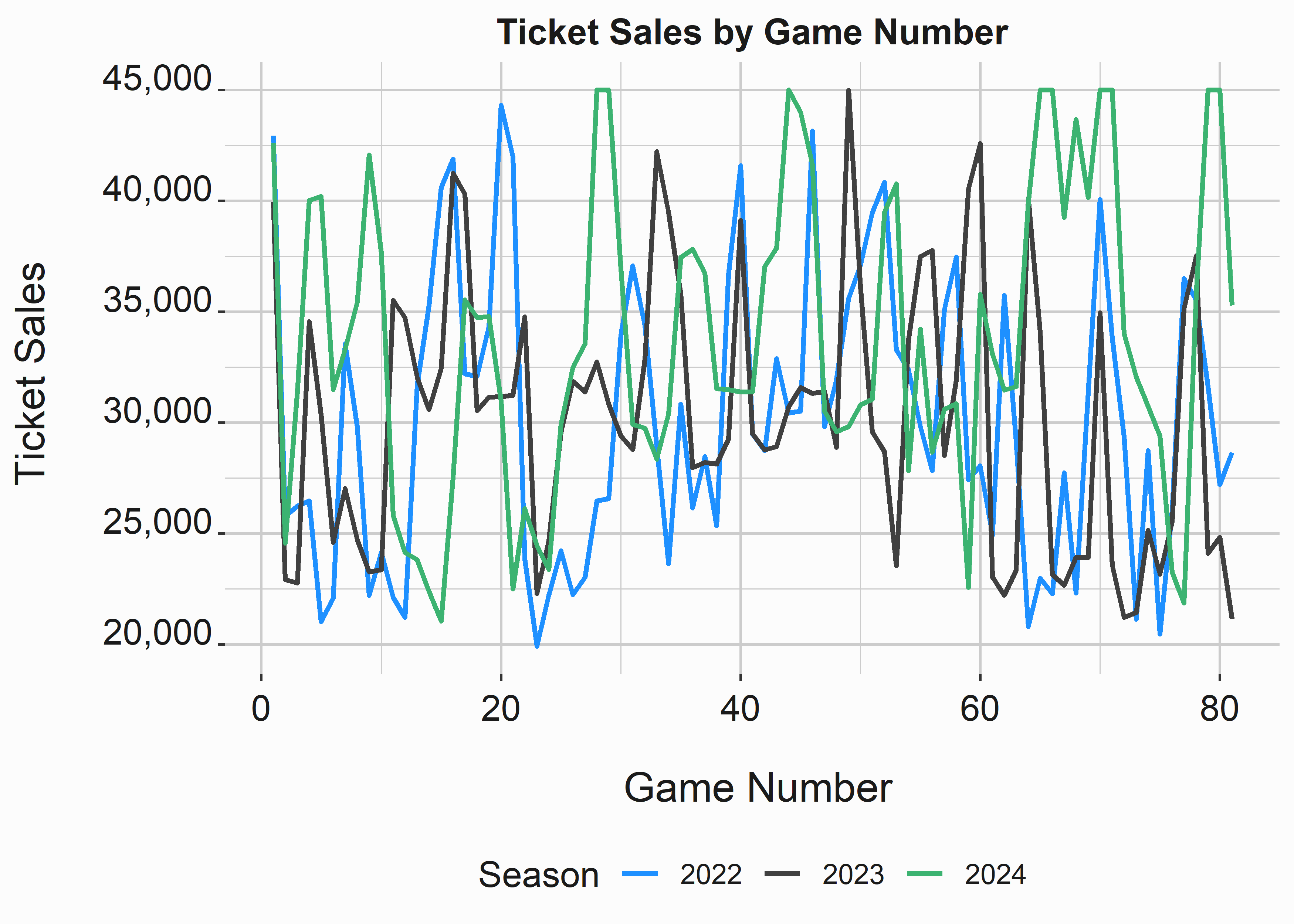

3.4 Line and tile plots

Line plots and tile plots can be used in various ways. Line plots tend to be used to demonstrate some sort of longitudinal trend. Tile plots can help to visualize data that is multidimensional and correlates with other features being displayed. Line plots will need some sort of grouping variable and can occasionally be frustrating to work with. In general, you put them together in the same way as the other plots you have seen. The following code produces the plot in figure 3.6.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Line plot

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

x_label <- ('\n Game Number')

y_label <- ('Ticket Sales \n')

title <- ('Ticket Sales by Game Number')

legend <- 'Season'

line_sales <-

ggplot2::ggplot(data = season_data,

aes(x = gameNumber,

y = ticketSales,

color = factor(season))) +

geom_line(size = .9) +

scale_color_manual(legend, values = palette) +

scale_y_continuous(label = scales::comma) +

xlab(x_label) +

ylab(y_label) +

ggtitle(title) +

graphics_theme_1 + theme(legend.position = "bottom")Line plots are a mainstay of analysis. They are typically leveraged to demonstrate change over time or some other series of data points. You should be pretty familiar with them. A word of warning is that they can become busy. Perhaps this plot would be better if the lines were placed on their own seperate graph.

Figure 3.6: Line and Tile Plots

It appears that there is some degree of seasonality in the data. We can see that there are very few games with relatively low attendance during the middle of the season. Perhaps this is because school is out in the summer months and it helps bolster attendance. Baseball also doesn’t have other major sports competing with them during these months.

If you look past the sixtieth game you will notice that 2024 has a surge in attendance. Maybe this is because they were in a playoff race. Line graphs are also interesting because if you notice trend and seasonality you might be able to decompose those components using exponential smoothing or even a moving average. In practice, I have found limited use for these techniques in sports, but it is something to think about and to be aware of.

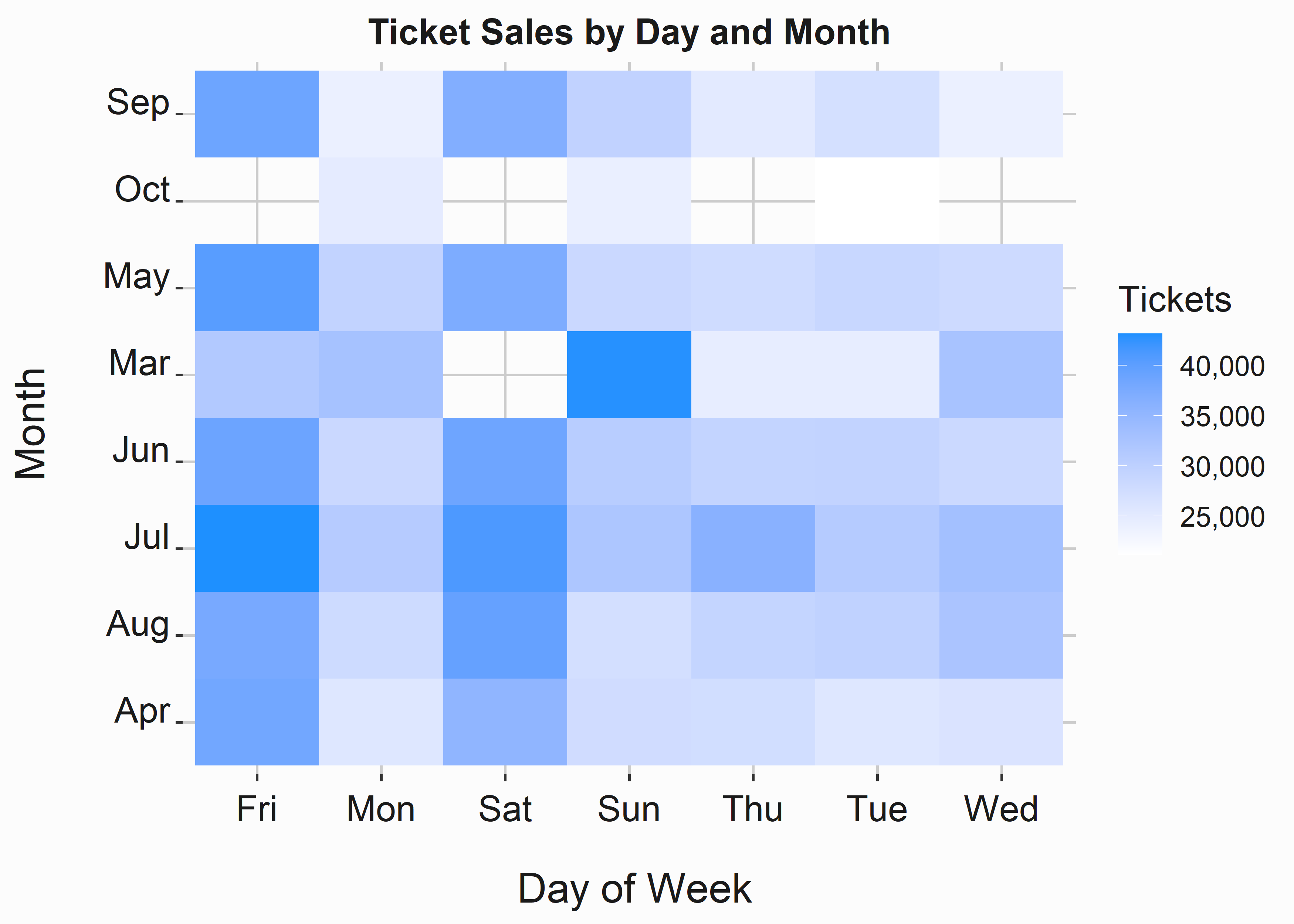

Tile plots (or heatmaps) add a level of dimensionality to data and can be extremely useful. The next example is a little different. We need to do some aggregation on the data before visualizing it. We’ll use the dplyr for most transformations found in this book. It just makes life easier. This is very different than what you will tend to see in languages such as python (unless it has been ported). It uses the pipe %>% to say the words then do. You’ll be seeing a lot more of it so try it out on some data. We are simply selecting some columns, grouping them, and then creating an aggregation. It feels similar to SQL. I wonder why?… This plot can be seen in figure 3.7.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Tile plot or heat map

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

x_label <- ('\n Day of Week')

y_label <- ('Month \n')

title <- ('Ticket Sales by Day and Month')

# compress data into an easier format

sd_comp <- season_data %>%

select(dayOfWeek,month,ticketSales) %>%

group_by(dayOfWeek,month) %>%

summarise(avgSales = mean(ticketSales))

tile_sales <-

ggplot2::ggplot(data = sd_comp,

aes(x = dayOfWeek,

y = month,

fill = avgSales)) +

geom_tile() +

scale_fill_gradient(low = "white", high = "dodgerblue",

name = 'Tickets',label = scales::comma) +

xlab(x_label) +

ylab(y_label) +

ggtitle(title) +

graphics_theme_1

Figure 3.7: Tile Plots

How do we interpret this data? We can clearly see that Friday and Saturday tend to have higher average ticket sales. This shouldn’t be a surprise. It also looks like Sundays in March did well. Beware! That is likely an artifact from a reduced sample size. Overall, Heatmaps do a good job of visualizing correlations, but they can be misleading. Be careful with them and always consider sampling issues.

You can also pump dplyr data directly into ggplot. See below.

season_data %>%

select(dayOfWeek,month,ticketSales) %>%

group_by(dayOfWeek,month) %>%

summarise(avgSales = mean(ticketSales)) %>%

ggplot2::ggplot(aes(x = dayOfWeek,

y = month,

fill = avgSales)) +

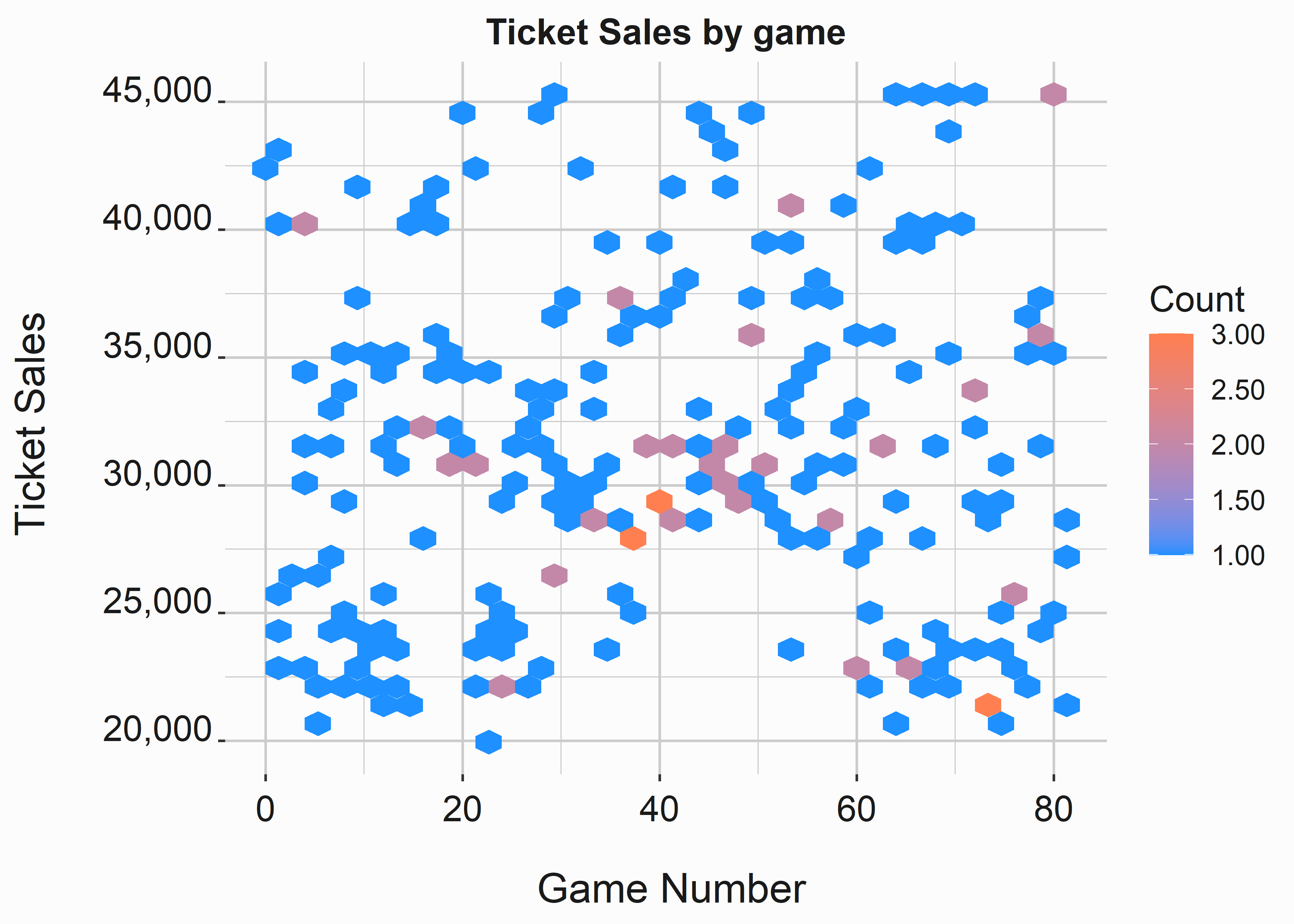

geom_tile() Let’s also take a look at a variation of a heatmap called a hex plot. It can be used in slightly different ways. You can see an example of the hex plot in figure 3.8.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Hexplots

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

x_label <- ('\n Game Number')

y_label <- ('Ticket Sales \n')

title <- ('Ticket Sales by game')

hex_sales <-

ggplot2::ggplot(data = season_data,

aes(x = gameNumber,

y = ticketSales)) +

geom_hex() +

scale_fill_gradient(low = "dodgerblue", high = "coral",

name = 'Count',label = scales::comma) +

scale_y_continuous(label = scales::comma) +

xlab(x_label) +

ylab(y_label) +

ggtitle(title)

Figure 3.8: Hex Plots

This graphic is a little different from the heatmap. It demonstrates the number of games that fall into each bin. I tend to use these plots when I have continuous variables on the x and y axis and I am interested in the density at each point. If you pay attention you can perceive some of the seasonality that is evident around game forty.

3.5 Bar plots

If you want to use a pie chart, don’t. Bar plots are almost always a better choice. Visualizing the relationships between area is simply easier in a bar plot. Bar plos are probably the most popular way to display data, but I find them lacking. Again, you really need to train yourself to think in distributions. Bar Plots are for counts. The basic bar plot produced by the following code can be seen in figure 3.9.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Bar plot version one

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

x_label <- ('\n Season')

y_label <- ('Proportion of Ticket Sales \n')

title <- ('Proportion of Ticket Sales by DOW')

bar_sales_pro <-

ggplot2::ggplot(data = season_data,

aes(y = ticketSales,

x = season,

fill = weekEnd)) +

geom_bar(stat = 'identity',position = 'fill') +

scale_fill_manual(values = palette, name = 'Weekend') +

scale_y_continuous(label = scales::percent) +

xlab(x_label) +

ylab(y_label) +

ggtitle(title) +

graphics_theme_1 + theme(legend.position = "bottom")

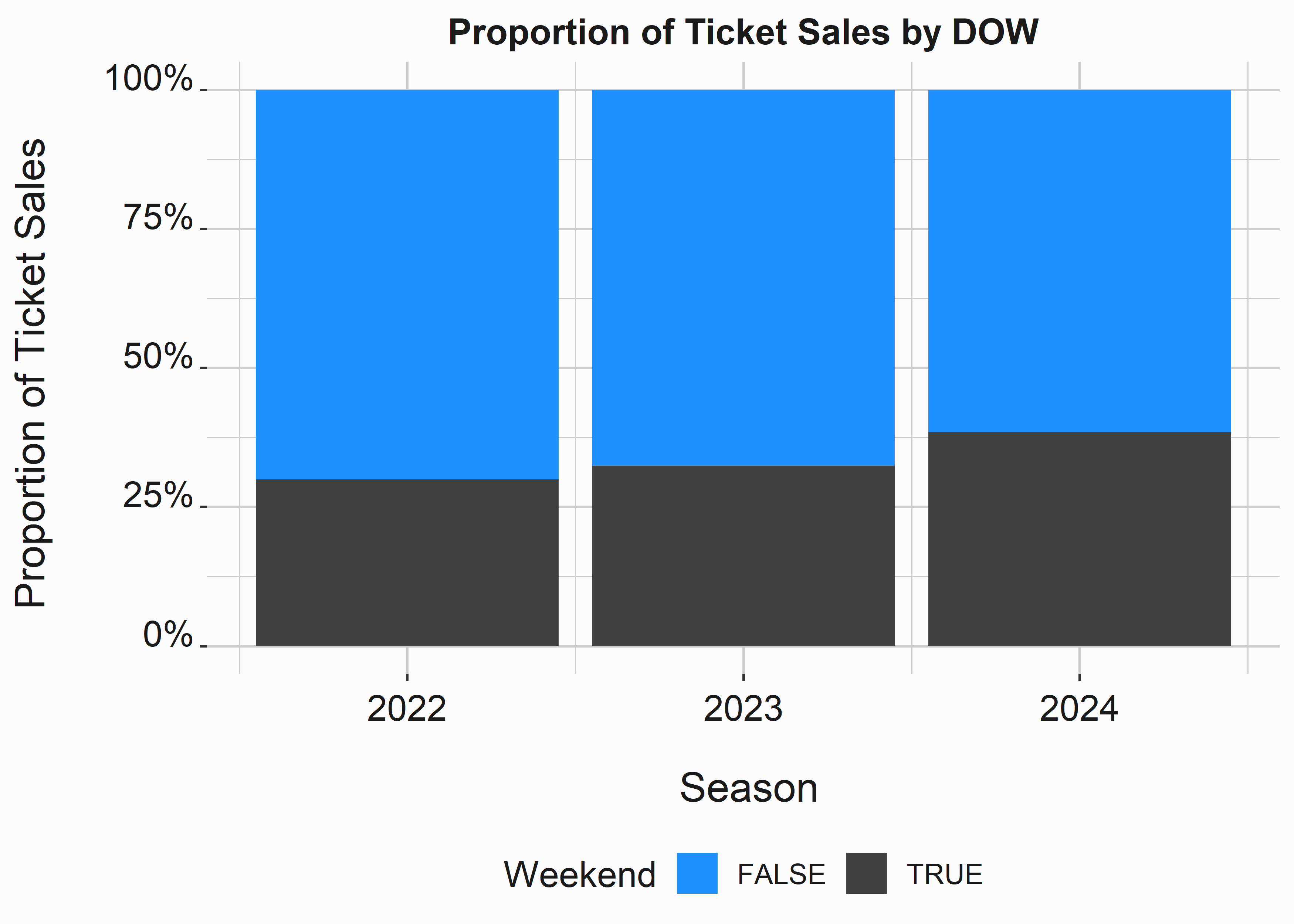

Figure 3.9: Proportion of sales by year and weekend

In this example we are looking at the percentages of tickets sold on the weekend vs. weekdays by season. This graph does a great job of it. We can clearly see that weekends make up a higher proportion of sales in 2024. We also know that weekdays make up the majority of sales.

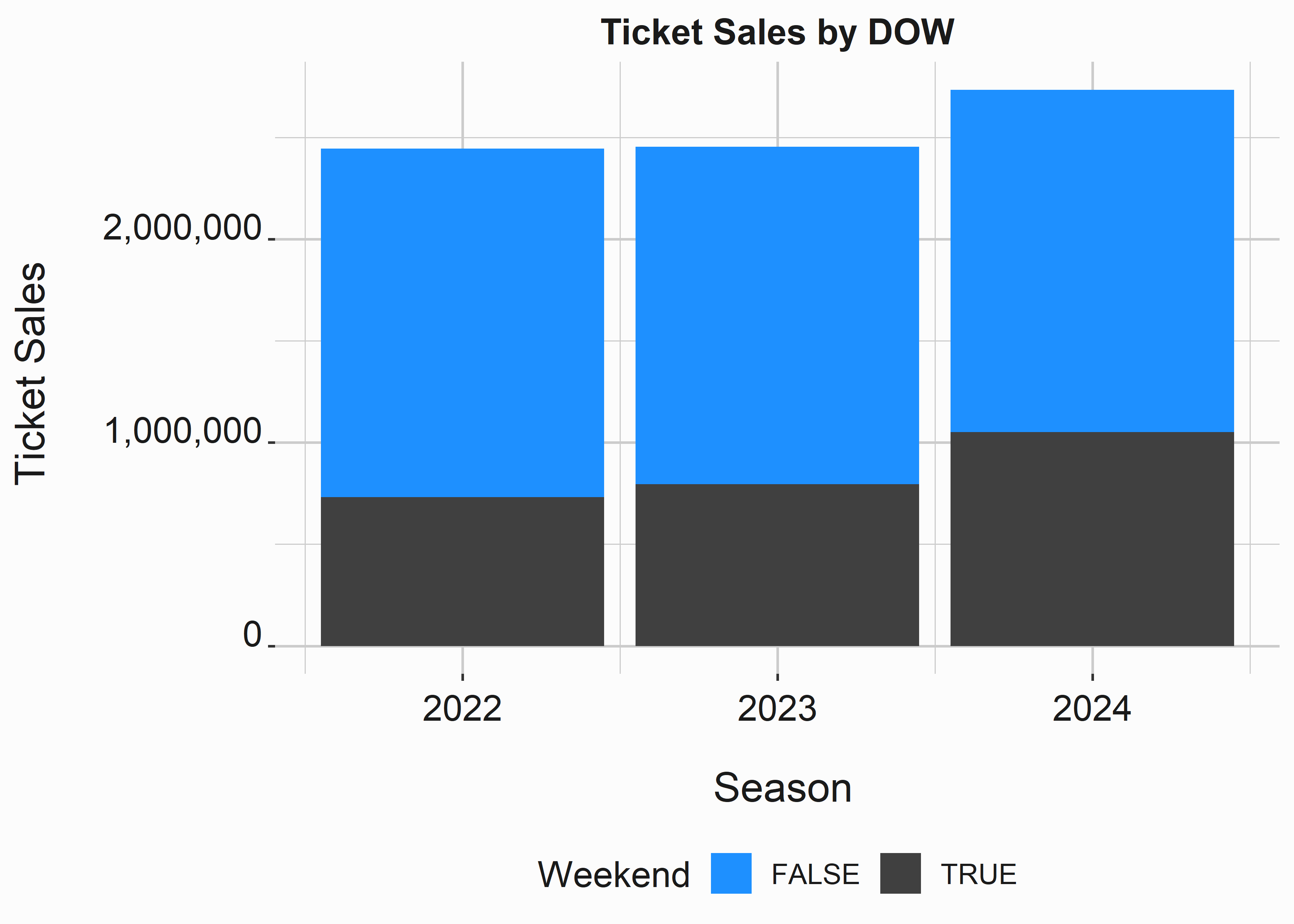

We can build a variation on this plot with the position argument. Now we can take a look at the overall numbers. This second bar plot can be viewed in figure 3.10.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Bar plot version two

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

x_label <- ('\n Season')

y_label <- ('Ticket Sales \n')

title <- ('Ticket Sales by DOW')

bar_sales <-

ggplot2::ggplot(data = season_data,

aes(y = ticketSales,

x = season,

fill = weekEnd)) +

geom_bar(stat = 'identity', position = 'stack') +

scale_fill_manual(values = palette, name = 'Weekend') +

scale_y_continuous(label = scales::comma) +

xlab(x_label) +

ylab(y_label) +

ggtitle(title) +

graphics_theme_1 + theme(legend.position = "bottom")

Figure 3.10: Barplot of sales

We can see that 2022 and 2023 are almost identical and 2024 had significantly more ticket sales. This is the type of plot you might use for descriptive reporting. This is something accounting would want to see. They don’t need to know why something happened, they typically just need the what. This is true in most cases that you will face. Make sure you clearly explain the what.

3.6 A final word on graphics

Be cautious about how you represent data. We just covered the absolute rudiments or creating graphs and demonstrated some of the most commonly used instruments. Always think about the simplest way to illustrate the point that you are trying to make. Bar plots are usually fine. I like to follow a few rules when building graphs, but don’t take my word for it. Many people will tell you exactly the same things.

- Never use a pie chart. They are more difficult to interpret than a bar plot

- Don’t use two Y axes. It is almost always better to use two graphs because the differences in scale or units can be confusing.

- Stick with a consistent color scheme.

- Stick with a consistent font scheme

- Don’t put too much on one graph. Too many colors or shapes make graphs confusing. Always simplify.

Additionally, we didn’t cover dynamic plots. R provides some interesting capabilities on this front. Shiny (Chang et al. 2022) allows you to build some cool interactive web apps. There are also innumerable tools such as Tableau 30 and Looker that provide good business intelligence capability. Often times these tools are easier to use for quick ad hoc data exploration, but there is a lot of utility in putting everything into code. It automatically documents your work for those that can read it. It also gives you a readily available reference. You will find that this work can tend to be repetitive. You will use a lot of variations on the same theme. Most code is already written. You just need to adapt it.

3.7 Summarizing the data

This section will make heavy use of an R package that we have already seen named dplyr (Wickham, François, et al. 2022). We’ll use dplyr because it is easy to read and is performant on most data sets that you’ll encounter. We’ll also reference a couple of other packages that are useful for summarizing data such as psych (Revelle 2022). Summarizing data is often an accouterment to graphs. You don’t always have to do it, but you will find yourself doing often.

Let’s create simple summary of ticket sales by the day of the week using dplyr.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Creating a summary statistics table

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

library(dplyr)

average_by_dow <-

FOSBAAS::season_data %>%

group_by(dayOfWeek) %>%

summarise(AverageSales = mean(ticketSales))| dayOfWeek | AverageSales |

|---|---|

| Fri | 38794.03 |

| Mon | 28243.46 |

| Sat | 38146.29 |

| Sun | 29690.38 |

| Thu | 28560.53 |

| Tue | 28217.72 |

| Wed | 28893.47 |

dplyr has a wide assortment of useful tools for manipulating data. I highly recommend leveraging it whenever possible. For edification, an identical table can be produced in base R using the by function:

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Creating a summary statistics table using 'by'

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

by(FOSBAAS::season_data$ticketSales,

FOSBAAS::season_data$dayOfWeek,function(x) mean(x))

#> FOSBAAS::season_data$dayOfWeek: Fri

#> [1] 38794.03

#> ---------------------------------------------

#> FOSBAAS::season_data$dayOfWeek: Mon

#> [1] 28243.46

#> ---------------------------------------------

#> FOSBAAS::season_data$dayOfWeek: Sat

#> [1] 38146.29

#> ---------------------------------------------

#> FOSBAAS::season_data$dayOfWeek: Sun

#> [1] 29690.38

#> ---------------------------------------------

#> FOSBAAS::season_data$dayOfWeek: Thu

#> [1] 28560.53

#> ---------------------------------------------

#> FOSBAAS::season_data$dayOfWeek: Tue

#> [1] 28217.72

#> ---------------------------------------------

#> FOSBAAS::season_data$dayOfWeek: Wed

#> [1] 28893.47There are many other data manipulation packages such as data.table (Dowle and Srinivasan 2021) and plyr (Wickham 2022b). Let’s take a look at a few more examples. You will frequently find yourself looking at quantiles. You can use this data to set simple fences for segmentation.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Getting quantiles

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

quants <- quantile(FOSBAAS::season_data$ticketSales,

probs = c(0,.10,.25,.5,.75,.9,1))

quants

#> 0% 10% 25% 50% 75% 90% 100%

#> 19920.0 22797.6 26126.5 30956.0 35664.0 40816.6 45000.0In this case we know that 25% of the observations are below 26,126.5 tickets sold. You can access the components of this object with brackets and an index. Many object in R can be accessed with indexes. This comes in handy when you are scripting.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Getting quantiles

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

quants[3]

#> 25%

#> 26126.5Turning data from long to wide format and vise-versa is something that is also a common task. Perhaps you would like to see the Giants and Baltimore and you need to reformat the data. This will be a little more complex, but it demonstrates how logically this system operates. We’ll use the dplyr and tidyr (Wickham and Girlich 2022) libraries to achieve this result. You can perform these tasks in SQL, but it won’t be as intuitive and user friendly to do so. Learn when to use SQL vs. R and vice-versa.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Converting to wide format

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

library(dplyr)

library(tidyr)

team_dow <-

FOSBAAS::season_data %>%

select(team,dayOfWeek,ticketSales) %>%

filter(team %in% c('SF','BAL')) %>%

group_by(team,dayOfWeek) %>%

summarise(medianSales = median(ticketSales),

games = n()) %>%

tidyr::pivot_wider(names_from = team,

values_from = c(medianSales,games)) %>%

mutate(difference = medianSales_BAL - medianSales_SF) %>%

arrange(difference) | dayOfWeek | medianSales_BAL | medianSales_SF | games_BAL | games_SF | difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sun | 28209.0 | 42928.0 | 2 | 1 | -14719.0 |

| Sat | 29787.0 | 43999.0 | 1 | 1 | -14212.0 |

| Thu | 22561.0 | 35357.5 | 3 | 2 | -12796.5 |

| Fri | 33734.0 | 43608.5 | 3 | 2 | -9874.5 |

| Wed | 26301.5 | 28773.0 | 4 | 1 | -2471.5 |

| Mon | 25658.5 | 25759.0 | 2 | 1 | -100.5 |

| Tue | 26464.0 | 26233.0 | 3 | 1 | 231.0 |

We now have a table that tells us exactly what we want to know. In practice you will probably need this data in long format more often than wide format. Let’s pretend we want to graph this data. Because of the way ggplot works you will probably want to convert this data to long format like in the example below.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Converting to long format

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

library(dplyr)

library(tidyr)

team_dow_long <-

team_dow %>%

select(dayOfWeek, medianSales_BAL,medianSales_SF) %>%

tidyr::pivot_longer(!dayOfWeek,

names_to = "club",

values_to = "medianSales")

| dayOfWeek | club | medianSales |

|---|---|---|

| Sun | medianSales_BAL | 28209.0 |

| Sun | medianSales_SF | 42928.0 |

| Sat | medianSales_BAL | 29787.0 |

| Sat | medianSales_SF | 43999.0 |

| Thu | medianSales_BAL | 22561.0 |

| Thu | medianSales_SF | 35357.5 |

This data will be much easier to use in ggplot. For the most part, these are the main operations you will be performing. They can be much more complex, but you just went through the main building blocks. If you understand what we just covered, you will be surprised at how far you can take it.

3.7.1 Getting statistical information

I also thought it might be useful to mention a few ways to get statistical data without having to calculate it yourself. R excels here and several people have extended it’s capabilities. I’ll show you a couple of the ones I have used the most. The psych (Revelle 2022) library contains many useful functions for manipulating and summarizing data. We’ll use describe here to get some basic statistical features of the data.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Summary stats psych

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

library(psych)

psy_desc <-

t(data.frame(psych::describe(FOSBAAS::season_data$ticketSales)))| X1 | |

|---|---|

| vars | 1.0000000 |

| n | 243.0000000 |

| mean | 31411.0370370 |

| sd | 6578.2640431 |

| median | 30956.0000000 |

| trimmed | 31107.2256410 |

| mad | 7103.1366000 |

| min | 19920.0000000 |

| max | 45000.0000000 |

| range | 25080.0000000 |

| skew | 0.3095442 |

| kurtosis | -0.7500429 |

| se | 421.9958351 |

This gives you a good overview of what the structure of the ticket sales data looks like. It’s also a good opportunity to point out one of R’s quirks. The psych package and the Hmisc (Harrell 2022) package both have a function with the same name (describe). They even do similar things. Be cautious with dependencies because they can cause problems. When you load packages they can overwrite each other. To get around this issue you can always leverage the full namespace: psych::describe instead of describe.

The following example uses the Hmisc package to display some summary statistics.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Summary stats Hmisc

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

hmisc_desc <- (Hmisc::describe(FOSBAAS::season_data$ticketSales))

hmisc_desc <- unlist(hmisc_desc$counts)

hmisc_desc <- as.data.frame(hmisc_desc)You can remove libraries from your environment using a couple of different commands: (unloadNamespace("Hmisc") and detach("package:Hmisc")) Read the documentation to understand the differences.

| n | 243 |

| missing | 0 |

| distinct | 234 |

| Info | 1 |

| Mean | 31411 |

| Gmd | 7517 |

| .05 | 22115 |

| .10 | 22798 |

| .25 | 26127 |

| .50 | 30956 |

| .75 | 35664 |

| .90 | 40817 |

| .95 | 43602 |

As you can see, somebody else has done the hard work for you. You just need to know where to look. Keep in mind that not all R packages are high quality. This software is user-generated and provided for free. While there are lots of reputable packages, there are also lots that are poorly written. It is sometimes useful to look for provenance.

3.7.2 Building models and basic statistics

We’ll apply more rigor to our models as we progress through the ensuing chapters. However, I want to introduce a couple of concepts in this chapter. We will add to the complexity as we move into actual projects.

3.7.2.1 ANOVA

An analysis of variance is a commonly used tool to gauge differences between groups. We are only going to take a cursory look at one version of ANOVA. There are lots of different types of ANOVA and you’ll want to put some time into understanding when and how to use them. Additionally, ANOVA output is equivalent to regression output. You’ll use it when you want to understand differences between groups. There are other ways to analyze the differences between groups such as a students T test and other non-parametric methods. .

The following example is a one-way ANOVA with a covariate. We want to look at the differences in ticket sales by promotion by the day of the week. We can begin by building a fequency table.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Build a frequency table

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

table(FOSBAAS::season_data$promotion)

#>

#> bobblehead concert none other

#> 16 8 212 7Each group has completely different representations which would indicate that this is not a balanced design. Does that matter? It certainly could. Test for group differences using by the aov function.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# One Way ANOVA

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

mod <- aov(ticketSales ~ promotion + dayOfWeek,

data = FOSBAAS::season_data)

#summary(mod)| term | df | sumsq | meansq | statistic | p.value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| promotion | 3 | 865001255 | 288333752 | 12.26602 | 2e-07 |

| dayOfWeek | 6 | 4130134954 | 688355826 | 29.28337 | 0e+00 |

| Residuals | 233 | 5477064783 | 23506716 | NA | NA |

We’ll discuss designing experiments (DOE) in a later chapter. For now, we’ll simply walk through some of the output. We aren’t being rigorous here. Basically, our P Value looks good and we have an F statistic that isn’t super small. We can move forward. Let’s take a look at these statistics in a graph.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Viewing group means

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

library(dplyr)

graph_table <- FOSBAAS::season_data %>%

select(promotion,ticketSales,dayOfWeek,daysSinceLastGame) %>%

group_by(promotion,dayOfWeek) %>%

summarise(sales = mean(ticketSales),

daysSinceLastGame = mean(daysSinceLastGame),

N = n(),

sd = sd(ticketSales),

se = sd/sqrt(N))

x_label <- 'Day of Week'

y_label <- 'Mean ticket sales'

title <- 'Group means and standard error: promos and sales'

se <-

ggplot(graph_table, aes(y=sales,

x=reorder(dayOfWeek,sales,mean),

color=promotion)) +

geom_errorbar(aes(ymin = sales-se, ymax = sales+se),

width =.3,size = 1,

position = position_dodge(0.25)) +

geom_point() +

scale_color_manual(values = palette) +

scale_y_continuous(label = scales::comma) +

xlab(x_label) +

ylab(y_label) +

ggtitle(title) +

graphics_theme_1

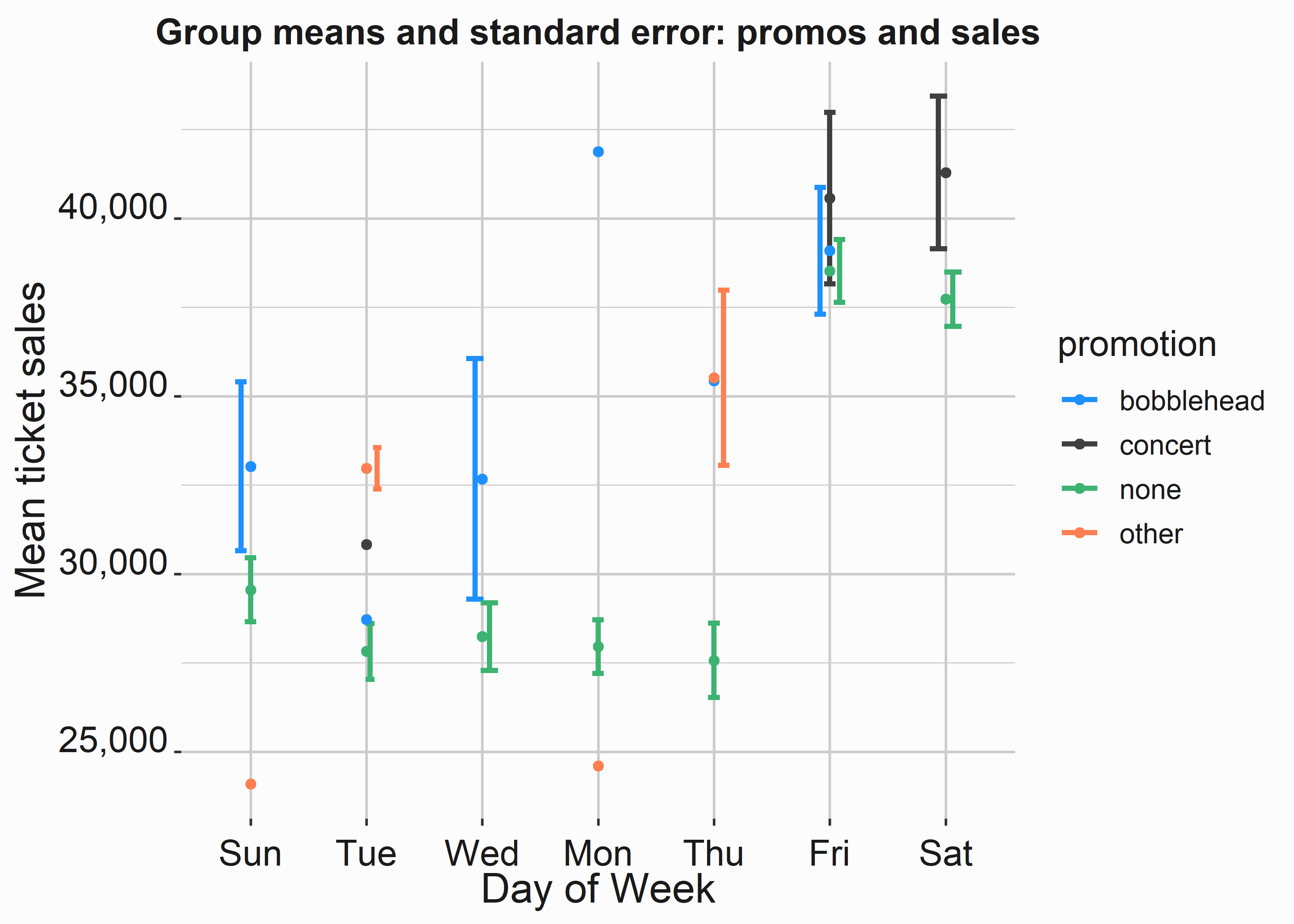

Figure 3.11: Group means and standard error by promotion and dow

This model output isn’t incredibly informative, but the graph gives you a lot of information. Once you have your model constructed you can access all the parts with a dollar sign: mod$terms. There is a lot of information to explore in these models when you begin making them more complex. In this case, we can see that we have some sample issues.

We can also see that certain promotions may be more effective than others and that the day of the week may have an impact on how effective the promotion might be in absolute terms. Let’s apply a Tukey test31 to this data. This test will help us compare pairs of means and is based on the students t test. If you aren’t familiar with these tests, do a little research on them. They can be useful.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Tukey test

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

tu_test <- TukeyHSD(mod)| diff | lwr | upr | p adj | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| concert-bobblehead | 4465.5000 | -967.0665 | 9898.067 | 0.1475821 |

| none-bobblehead | -4442.5448 | -7695.2441 | -1189.845 | 0.0027589 |

| other-bobblehead | -3646.7321 | -9332.1099 | 2038.646 | 0.3474454 |

| none-concert | -8908.0448 | -13426.6337 | -4389.456 | 0.0000042 |

| other-concert | -8112.2321 | -14605.3911 | -1619.073 | 0.0076108 |

| other-none | 795.8127 | -4023.7710 | 5615.396 | 0.9737610 |

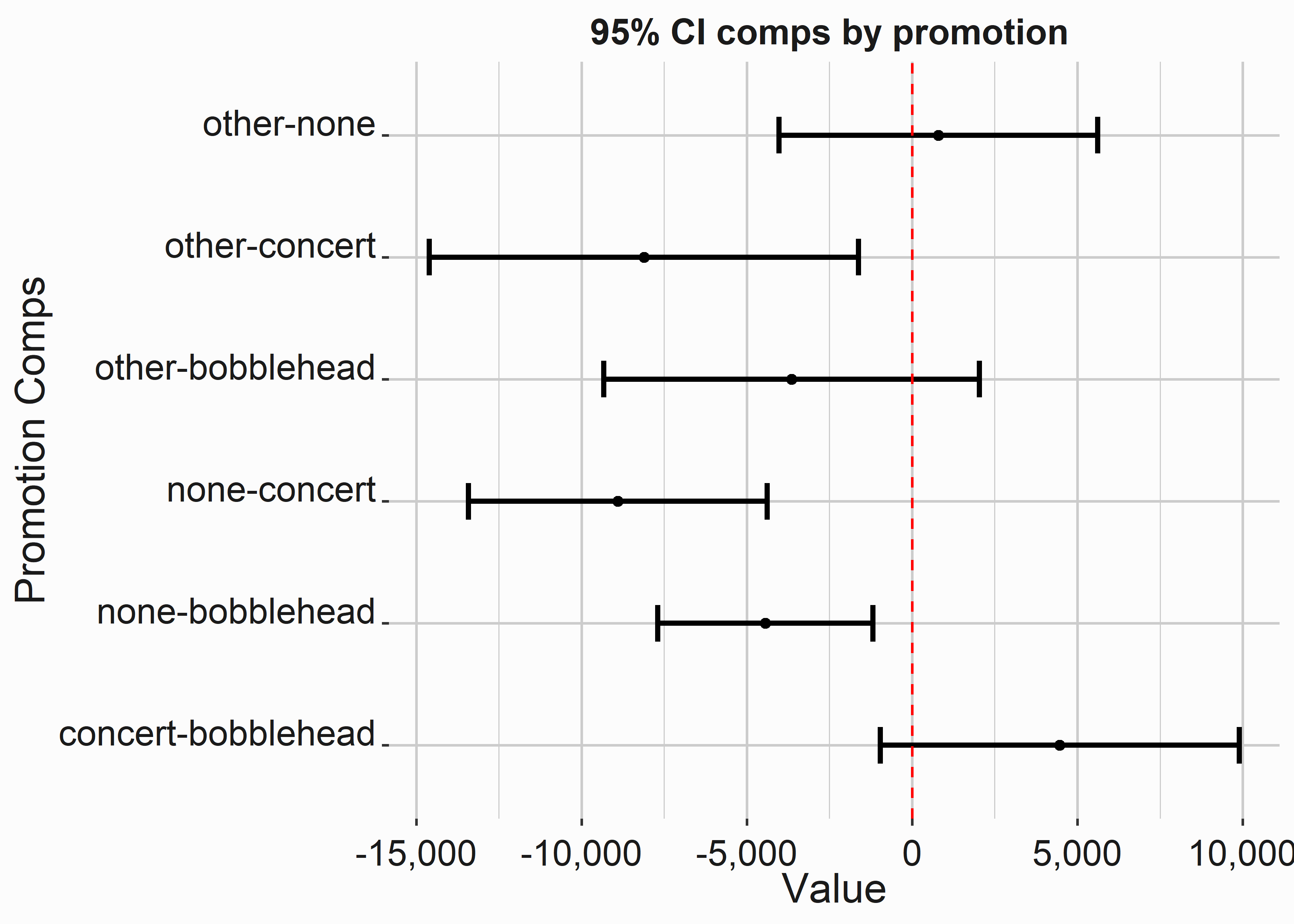

In this case, the mean ticket sales for bobbleheads and concerts aren’t significantly different from each other. What does this mean? If your KPI is ticket sales and there are different marginal costs associated with concerts and bobbleheads then the less expensive option might be preferable. Let’s visualize these results.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Viewing group means

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

x_label <- 'Value'

y_label <- 'Promotion Comps'

title <- '95% CI comps by promotion '

tu_comp_graph <-

ggplot(tu_comp, aes(x=diff,

y=promotion)) +

geom_errorbar(aes(xmin = lwr, xmax = upr),

width =.3,size = 1) +

geom_point() +

scale_x_continuous(label = scales::comma) +

xlab(x_label) +

ylab(y_label) +

ggtitle(title) +

geom_vline(xintercept = 0,color = 'red',lty = 2) +

graphics_theme_1

Figure 3.12: Group means and standard error by promotion and dow

If an interval crosses zero, it isn’t significant and we can potentially disregard the information as inconclusive.

3.7.2.2 Linear Regression

We’ll go into regression in more detail in several later chapters. Functionally, the output is the same as an ANOVA.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Creating a simple linear model

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

ln_mod <- lm(ticketSales ~ team+dayOfWeek+month+

daysSinceLastGame+openingDay+promotion,

data = FOSBAAS::season_data)

ln_mod

#>

#> Call:

#> lm(formula = ticketSales ~ team + dayOfWeek + month + daysSinceLastGame +

#> openingDay + promotion, data = FOSBAAS::season_data)

#>

#> Coefficients:

#> (Intercept) teamATL teamBAL

#> 37993.73 -579.17 -612.86

#> teamBOS teamCHC teamCIN

#> 10479.61 8873.01 -196.89

#> teamCLE teamCOL teamCWS

#> -1047.45 -488.43 1914.73

#> teamDET teamFLA teamHOU

#> -445.81 -1755.96 5301.38

#> teamKAN teamLAA teamLAD

#> -1729.86 4876.19 11798.00

#> teamMIL teamMIN teamNYM

#> -3877.18 330.59 4384.53

#> teamNYY teamOAK teamPHI

#> 7362.71 1123.20 3590.36

#> teamSD teamSF teamTB

#> -1422.63 3995.62 -1543.36

#> teamTEX teamWAS dayOfWeekMon

#> -2309.79 -1107.37 -8998.56

#> dayOfWeekSat dayOfWeekSun dayOfWeekThu

#> -247.95 -8519.78 -8806.70

#> dayOfWeekTue dayOfWeekWed monthAug

#> -8724.49 -8947.95 -79.88

#> monthJul monthJun monthMar

#> 5264.39 2986.79 -1522.76

#> monthMay monthOct monthSep

#> 184.91 -1699.57 -1255.60

#> daysSinceLastGame openingDayTRUE promotionconcert

#> 279.20 3986.05 -929.53

#> promotionnone promotionother

#> -4598.88 -2877.06| st_error | r_square | adj_r_square | f_stat |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1980.077 | 0.925496 | 0.9093972 | 57.48835 |

You can use these coefficients to explain the impact of specific variables. How many tickets is the month of July worth? The coefficient (5264.39) represents this impact. July gives you a five-thousand ticket bump. You can also use the model to make predictions. This model is completely overfit, but that doesn’t matter at this point. We’ll look at ways to make sure you don’t overfit models in subsequent chapters. Let’s put these predictions on a graph.

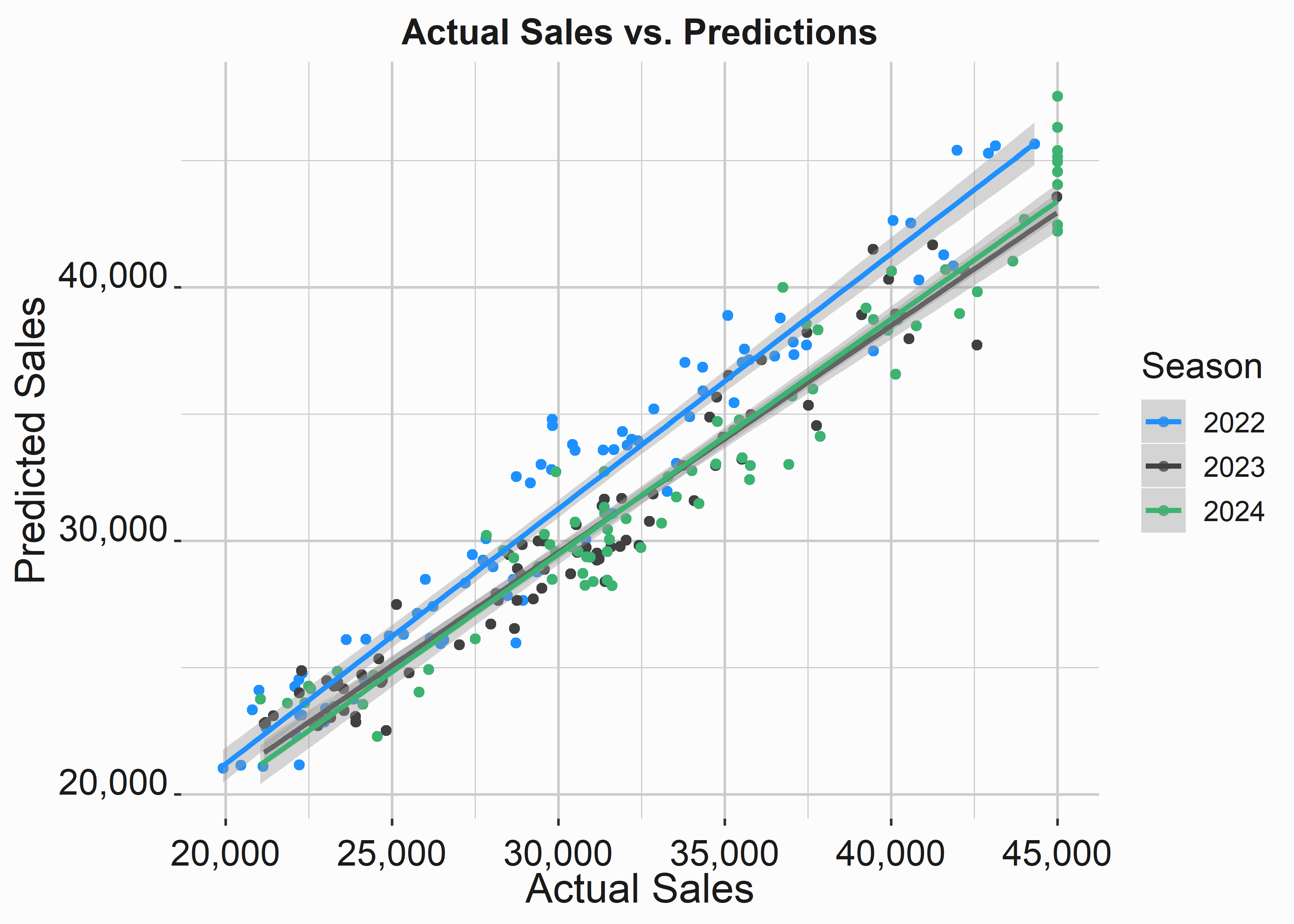

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Using the regression output

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

seasons <- FOSBAAS::season_data

seasons$pred <- predict(ln_mod)

x_label <- 'Actual Sales'

y_label <- 'Predicted Sales'

title <- 'Actual Sales vs. Predictions'

legend <- ('Season')

sales_mod <-

ggplot(seasons, aes(x = ticketSales,

y = pred,

color = factor(season))) +

geom_point() +

stat_smooth(method = 'lm', se = T) +

scale_color_manual(legend,values = palette) +

scale_x_continuous(label = scales::comma) +

scale_y_continuous(label = scales::comma) +

xlab(x_label) +

ylab(y_label) +

ggtitle(title) +

graphics_theme_1

Figure 3.13: Prediction vs. acutal values

We can see that the model does a pretty good job of approximating sales. We’ll go through more complete examples later.

3.8 Key concepts and chapter summary

Exploring your data is a fundamental component of analysis. You are looking for useful patterns that might make more sophisticated analysis possible. You are also looking for things like missing data and sparsity. Graphs are typically the easiest way to accomplish this goal. They are also the best method for communicating results.

We covered several key concepts in this chapter:

- It is important to create a consistent design language for your graphs. Pay attention to colors.

- Certain graphs are better at representing specific data. You often don’t need exotic plots to convey information. You’ll use variations on a few different themes.

- Summarizing data can be done in several ways. There are multiple tools that you can use to reshape and summarize data. You can even implement your own methods relatively easily.

- R makes it easy to explore and deploy a wide variety of statistical methods.

- When interpreting or communicating findings the simplest explanation is usually the best. Most people will not care how you did something. Let them ask you for more context.

Think of this chapter as a reference. You just went through the basic Business Intelligence and analytics tools that you will use for data exploration. You can also use Business Intelligence tools like Tableau to add additional dimensions to your illustrations. If you want to build custom websites R provides tools to accomplish this as well. You could even use javascript or python to accomplish the same thing.