4 Structuring Projects

Framing projects is an overlooked component of analytics exercises. These projects often begin in medias res. You cobble some data together and start throwing models at it to get a result. Create a basic wireframe of your project before you begin. It’ll help keep your scope in check and force you to project-manage your work. You can loosely break these analytics projects into six parts, each of which may have sub-components:

- Defining a measurable goal or hypothesis

- Data collection and management

- Modeling the data

- Evaluating your results

- Communicating the results

- Deploying the results

This can often be an iterative process. There could be numerous questions that you have to answer about what tools you will need, whether you have the internal resources, what is the return on investment, how long this will take, whether anybody will use it, whether we have done this before, and if so, what were the results, etc. This process is also more helpful when you are just beginning to do this work. The seasoned analyst will have a good idea of where to start on a project through experience.

The basic premise is always the same when working through one of these projects. You create objectives based on environmental considerations, build some programs to implement those objectives, and monitor performance. It is easy, but the process tends to be overlooked. Larger projects can smother and die under their weight if all of the considerations (including political considerations) aren’t considered. A good plan can help keep them breathing.

4.1 Defining goals

Defining your goals can take time and effort. You’ll likely need to translate your product into an operational tactic that can be understood and leveraged by a functional unit of the business. For example, a Sales team may say they want to sell more tickets and need more leads. A marketing team may say that they want to understand return on marketing investment. How do you translate these statements into a practical solution? Each request contains several questions.

Several management techniques look for root causes. One is aptly named “5 Whys” (Serrat 2017). These subjects are outside the scope of this book. We should understand why we are doing something to devise a plan. It sounds obvious, and you should consider this a critical component of defining a goal as a part of the discovery process. Let’s explore an example:

Your ticket sales manager says “that they need more leads to sell more season tickets.” What is this person asking? It could be one of several things, and some of these things may have evolved from how that person is incentivized. It is always interesting to think about how incentives guide behavior (see Freakonomics: A rogue economist explores the hidden side of everything (Levitt 2005). So what could our sales manager be saying?

- I want to make more phone calls. The number of calls causes us to sell more tickets.

- Our current leads are not closing at the rate I need to hit my goals.

- I need more leads to keep my guys working.

When you put these thoughts into the context of what motivates your sales manager, this simple statement could be insidious:

- I am out of ideas, and I am going to make my guys work harder.

- I want to execute my job. So give me what I want.

This shouldn’t be viewed through a negative lens. Some jobs are about executing, and it can get tedious. Look at your task as a way to escape the monotony and to help the sales team think more strategically. Help them escape the mire.

Let’s assume that the sales manager believes the number of calls directly correlates to the number of tickets sold. Why do they think this, and is this something that we can investigate? A simplistic method to explore this conclusion might be to see if the number of phone calls correlates with sales in any particular way. We could use formal and informal methods, but the easiest thing to do is put this data into tables and graphs.

4.1.1 Identifying goals

The data set FOSBAAS::aggregated_crm_data has three fields, and each row represents interactions with one customer. See ?FOSBAAS::aggregated_crm_data:

- A repID corresponding to a specific rep

- calls represent the number of calls the rep made to a specific person

- revenue represents the amount of revenue generated from the specific customer.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Aggregated CRM data

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

ag_sales_data <- FOSBAAS::aggregated_crm_data

library(dplyr)

agg_calls <-

ag_sales_data %>%

group_by(repID) %>%

summarise(calls = sum(call),

revenue = sum(revenue)) %>%

mutate(revByCall = revenue/calls) %>%

arrange(desc(revByCall))| repID | calls | revenue | revByCall |

|---|---|---|---|

| AFA0Z9M2M4LQ | 1388 | 1202116.0 | 866.0778 |

| 9GZT5Z5AOMKV | 1340 | 1082318.7 | 807.7005 |

| QO0YHBN8KRMK | 1320 | 1006951.6 | 762.8421 |

| QTR3JJJ5J6GJ | 1358 | 993549.1 | 731.6267 |

| RJ7CCATUH4Q1 | 1312 | 927215.9 | 706.7194 |

| HOMV3XQW32LW | 1372 | 851999.3 | 620.9908 |

| S0Y0Y2454IU2 | 1344 | 815876.8 | 607.0512 |

| YOZ51B6A2QMB | 1384 | 804274.7 | 581.1233 |

| MBT9G0X70NTI | 1334 | 752486.0 | 564.0825 |

| 0LK62LATB8E3 | 1326 | 700451.1 | 528.2437 |

Why are some salespeople more effective? Perhaps someone called in and bought six of the most expensive seats, which skews the results. Are the call numbers correlated to revenue? The cor function will give us the correlation coefficient.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Correlation coefficient

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

cor(agg_calls$calls,agg_calls$revenue)

#> [1] 0.2589937Overall, calls are weakly correlated with revenue (A higher number is better). Why?

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Box plots of revenue by sales rep

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

x_label <- 'Rep ID'

y_label <- 'Revenue by sale'

title <- 'Revenue by sale by rep'

sales_box <-

ggplot(ag_sales_data, aes(y=revenue,

x=factor(repID))) +

geom_boxplot(fill = palette[1]) +

scale_color_manual(values = palette) +

scale_y_continuous(label = scales::dollar) +

xlab(x_label) +

ylab(y_label) +

ggtitle(title) +

graphics_theme_1 +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 90, size = 8,

vjust = 0,

color = "grey10"))

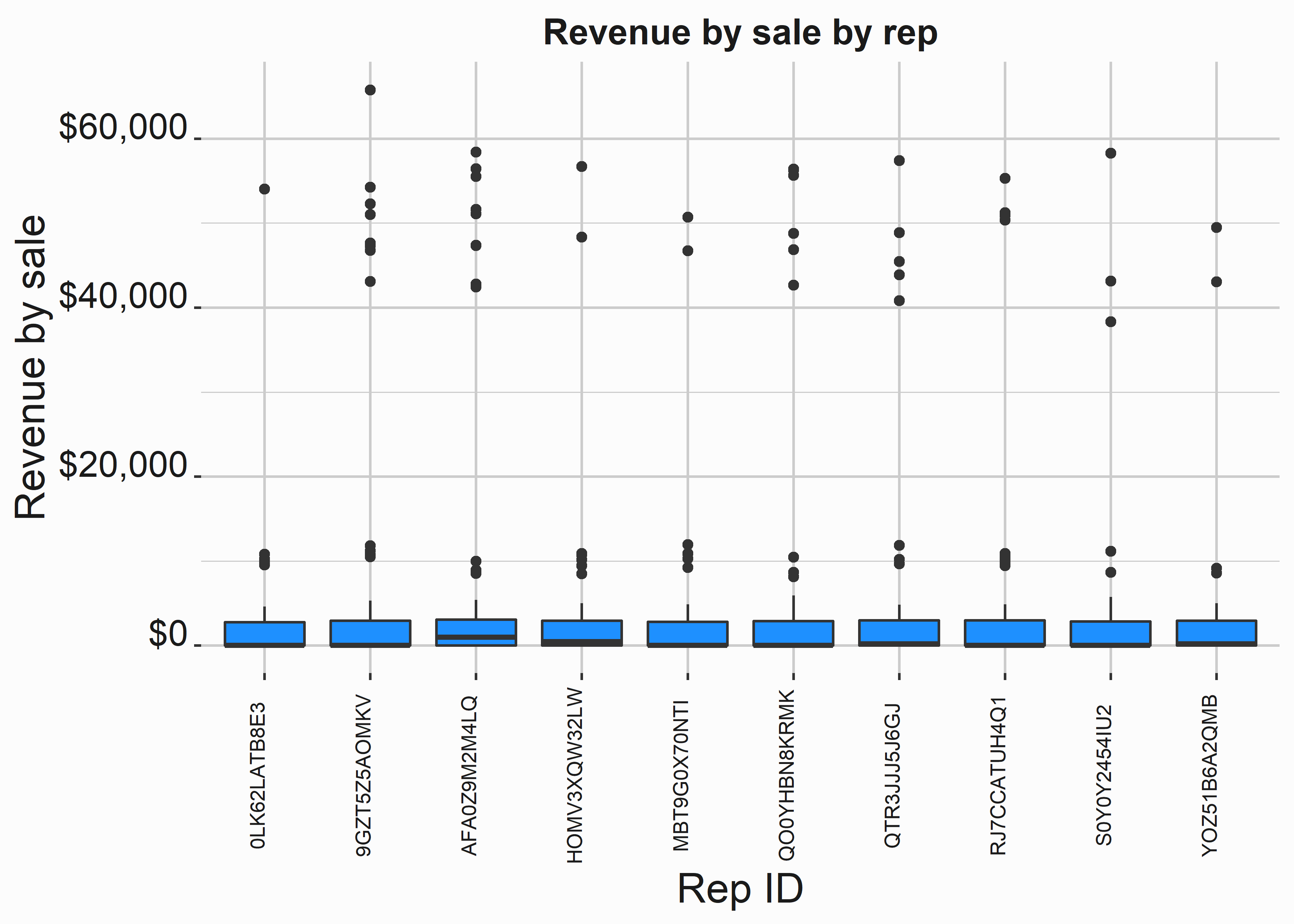

Figure 4.1: Boxplot of revenue by rep

We can see from the boxplots in figure 4.1 that average sales by customer is reasonably equivalent. However, some reps have far fewer outliers. A relatively small number of sales drives the differences we see between reps. You can get summary stats by a representative by using psych::describe.by(ag_sales_data\$revenue,ag_sales_data\$repID).

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Cumulative revenue by rep by customer

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

ag_sales_line <-

ag_sales_data %>% group_by(repID) %>%

mutate(cumSum = cumsum(revenue),

observation = seq(1:500))

x_label <- 'Customer'

y_label <- 'Revenue'

title <- 'Revenue generated per rep by customer'

sales_line <-

ggplot(ag_sales_line, aes(y = cumSum,

x = factor(observation),

group = repID,

color = repID)) +

geom_line() +

scale_color_manual(values = palette,guide = FALSE) +

scale_y_continuous(label = scales::dollar) +

xlab(x_label) +

ylab(y_label) +

ggtitle(title) +

graphics_theme_1 +

theme(axis.title.x=element_blank(),

axis.text.x=element_blank(),

axis.ticks.x=element_blank(),

panel.grid.major = element_line(colour = "white"),

panel.grid.minor = element_line(colour = "grey80"))

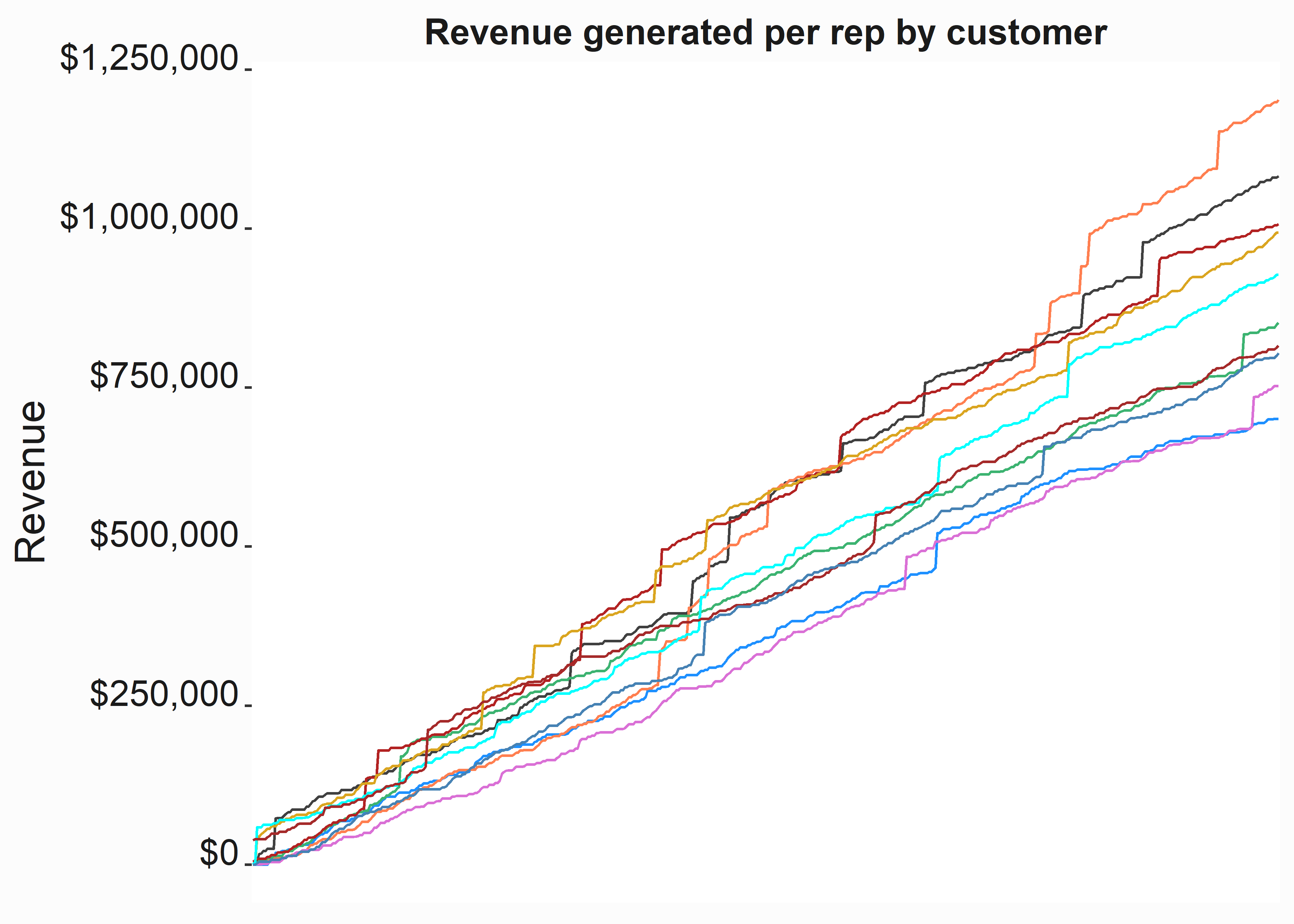

Figure 4.2: Cumulative revenue by rep

We can verify this without looking at the actual stats by looking at the jumps in these line graphs. We will also look at some statistics to see if there is anything else we can understand. Let’s answer a couple of questions:

- Are specific reps more efficient with phone calls?

- Are specific reps more efficient with customers?

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Failed calls and customers by rep

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

failures <-

ag_sales_data %>%

group_by(repID) %>%

filter(revenue == 0) %>%

summarise(failedCalls = sum(call),

failedCusts = n()) %>%

tidyr::pivot_longer(!repID,

names_to = "failure",

values_to = "value")

x_label <- ('\n Rep')

y_label <- ('Count \n')

title <- ('Failures by rep')

bar_sales <-

ggplot2::ggplot(data = failures,

aes(y = value,

x = reorder(repID,value,sum),

fill = failure)) +

geom_bar(stat = 'identity', position = 'dodge') +

scale_fill_manual(values = palette, name = 'failure') +

scale_y_continuous(label = scales::comma) +

xlab(x_label) +

ylab(y_label) +

ggtitle(title) +

coord_flip() +

graphics_theme_1 +

theme(legend.position = "bottom")

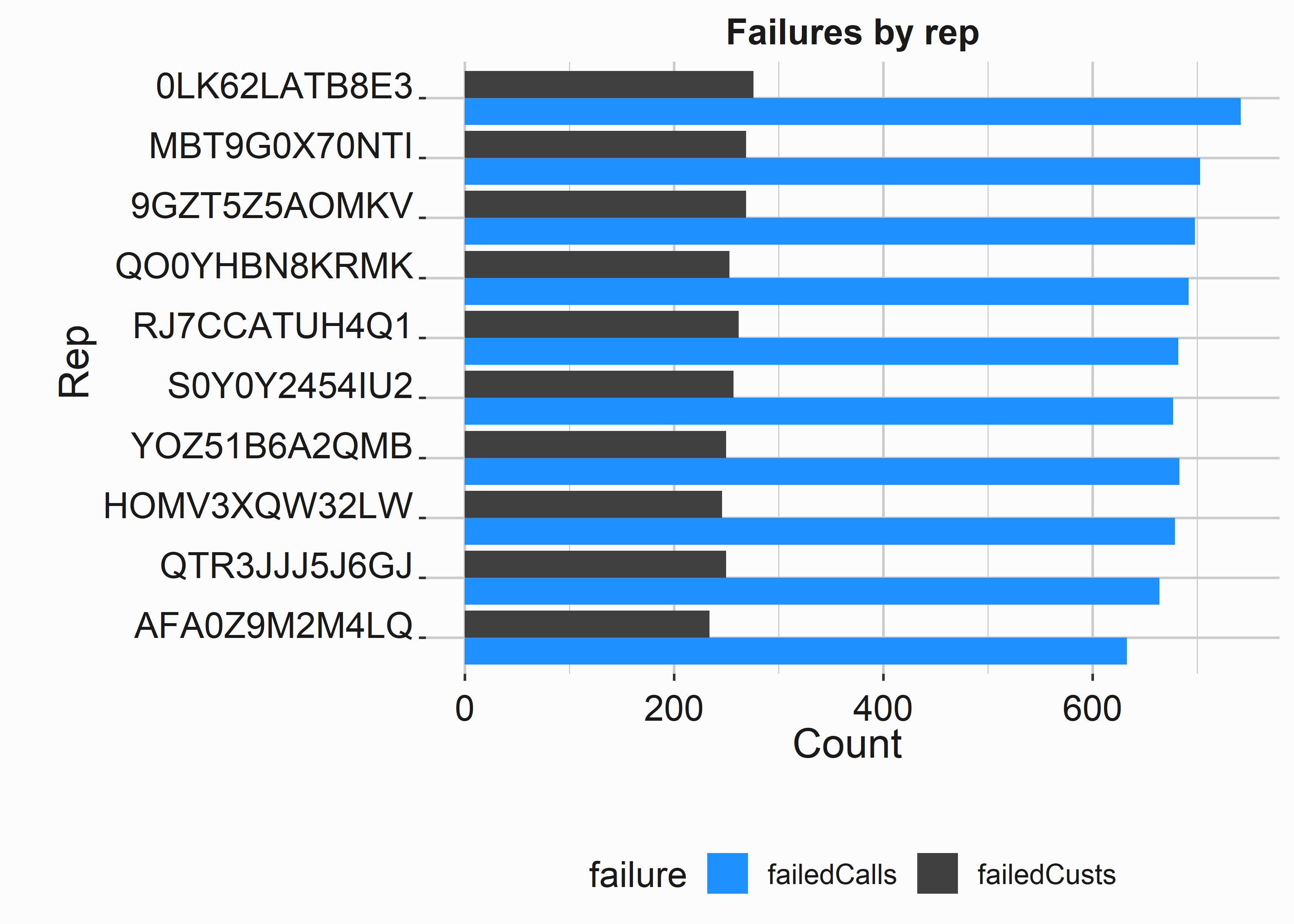

Figure 4.3: Call failures

Overall, no rep stands out as being more or less efficient, although there are some differences at the top and bottom. So let’s take a closer look at the distribution of sales revenue. Instead of a density plot, we’ll use some summary statistics and compare the highest and lowest performers.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# quantiles of sales

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

quants <- quantile(ag_sales_data$revenue,

probs = c(.5,.75,.9,.95,.975,.99,1))| x | |

|---|---|

| 50% | 0.000 |

| 75% | 2924.658 |

| 90% | 3694.630 |

| 95% | 4136.399 |

| 97.5% | 4631.669 |

| 99% | 10886.958 |

| 100% | 65789.102 |

At least 50% of customers that we interacted with resulted in no revenue. The top 1% of sales resulted in over $10,000.00 in revenue, and 25% of customers spent less than $2,924.00. Let’s isolate our top and bottom performers using the describe.by function.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# description of sales

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

ids <- c("0LK62LATB8E3","AFA0Z9M2M4LQ")

descriptives <-

psych::describe.by(

ag_sales_data[which(ag_sales_data$repID %in% ids),]$revenue,

ag_sales_data[which(ag_sales_data$repID %in% ids),]$repID)

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# description of sales

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

descriptives$`0LK62LATB8E3`[c(3,4,5,6,9)]

#> mean sd median trimmed max

#> X1 1400.9 2966.49 0 1036.41 54039.92

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# description of sales

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

descriptives$AFA0Z9M2M4LQ[c(3,4,5,6,9)]

#> mean sd median trimmed max

#> X1 2404.23 6747.1 963.96 1417.14 58428.16The average sale for our top rep was over 50% higher than our lowest performer’s. Additionally, the median sale was greater than zero, which means they had success more often. So let’s look at how much was generated by both reps at the upper end of the spectrum.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# quantiles of sales

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

ag_sales_data %>%

filter(repID %in% c('0LK62LATB8E3','AFA0Z9M2M4LQ'),

revenue >= quants[6]) %>%

group_by(repID) %>%

summarise(highRevenue = sum(revenue),

countRevenue = n())

#> # A tibble: 2 × 3

#> repID highRevenue countRevenue

#> <chr> <dbl> <int>

#> 1 0LK62LATB8E3 54040. 1

#> 2 AFA0Z9M2M4LQ 453204. 9Our top performer generated nine times as much revenue from the top 1% of spenders. When you couple this with a tendency to be more successful, you have your answer about why some reps do better. You have now answered one why. What have we established?

- The number of phone calls per rep weakly correlates with revenue.

- Some reps are marginally more effective than others in terms of efficiency.

- Some reps sell many more high-end deals than others.

What else should we look for?

- Are more experienced reps better at closing sales?

- What is the origin of sales? Were these sales called-in?

- Perhaps females tend to have better luck given the demographic distribution of purchasers.

- How does seasonality impact these figures? Perhaps reps began working at different times?

- Are there professional resellers hidden in these sales?

If the number of calls a rep makes is only weakly correlated to sales, your goal shouldn’t be having the reps make more phone calls. It also shouldn’t be to add more sales reps unless the sales rep’s experience or another factor impacts sales. These two tactics are the most common solutions you would hear; however, technology is rapidly changing this mindset. For example, artificial intelligence automates lead-warming, where sales might be more about up-sells than gauging or establishing interest.

The point of this section is that to establish goals, you need some objective justification of what those goals should be. Determine what is driving the desired outcomes before settling on a tactic. That sounds obvious, but it isn’t. The reasons could be political. Look at what might be incentivizing the behavior.

4.2 Collecting data

There is a lot to understand about data collection, and you will always be forced to confront the question of what data you need and how to acquire it. Some data is much easier to obtain. For instance, transactional data will likely abound. You will have access to several years of ticketing and CRM data. However, there may be problems with formatting and consistency. I would place data collection under a few headings:

- Transaction data from ticketing, CRM, or other internal systems

- Transaction data from external systems (perhaps you have an agency agreement for something like concessions)

- Third-party data. This might include data from vendors such as Acxiom.

- Public data. This includes sources such as Census data or information from legal records.

- Internal research data. This category contains surveys and other initiatives such as competitive intelligence.

This is also an excellent time to discuss how much data you may lack. A professional sports team isn’t Google, Facebook, or Amazon. These companies can build analytics capabilities around data in a far more sophisticated way than is possible along our vertical. You will have to partner with these companies or another third party if you would like to take advantage of those capabilities.

Furthermore, each of these tech companies are walled-gardens. They don’t like to share. You’ll have to contend with this fact. Think critically about how you use these capabilities. If you spend money on SEM32, you’ll want to ask yourself why. How does your market work? Are there multiple channels consumers can exploit to purchase tickets? It is easy to skew attribution. If I knew you would type “Game Hens tickets” into your search bar, it would be easy to attribute a sale to that activity. You must ask yourself if you should attribute that sale to your search-engine spend.

Internal sources such as survey results, transaction data, interaction data through phone calls, or loyalty programs offer some degree of reliability. However, depending on your geography, the legal environment may not allow you to leverage this data. There are numerous restrictions on leveraging, storing, and sharing data, such as:

- The California Consumer Privacy Act 33

- The Illinois biometric information privacy Act 34

- The Can-Spam Act 35

- The No-Call list 36

As long as you live in the United States, some or all of these laws impact how you can leverage your first or third-party data. This list is not even comprehensive. GDRP37 (a European privacy law) is far-reaching and does have some influence on what we can do in the United States. The future of commerce will undoubtedly make this arena more challenging to navigate as the use of biometrics becomes more prolific.

Additionally, data often needs to be more accurate. Where do third party data-brokers get their data? Sometimes they use a bank of names to determine if a person is a male or female, or African American vs. Asian: Washington = African American, Wang = Asian, Lopez = LatinX. LatinX represents a particular problem with culture and the notion of race. Third-party brokers (such as Axiom) source their data from multiple sources and model components of it. Working with third-party data can be difficult and frustrating unless you deal with massive datasets (uncommon in sports).

Internal research data may have required specific research instruments such as:

- IDI (in-depth interviews)

- Satisfaction surveys

- Conjoint studies

- Focus groups

- Brand-tracking studies

- Social listening

These sources can become stale rather quickly. They can also be expensive and often require specialized software and skill sets.

Operational data may not have a ready-made method for data collection. For example, let’s say that an Executive wants to understand the relationship between line length at concession stands relative to attendance. How will you get it? Do you have cameras installed with A.I. that tracks line length? No? You’ll have to collect manually, leveraging some rubric that can be easily explained and executed by front-line staff. What might a data collection plan look like? When determining how to collect data, thinking about the problem from the inside out is helpful. We’ll discuss this concept in more depth in chapter 9.

The main gist is that you need to focus on a couple of things:

- What questions are you trying to answer?

- What data do you need to answer those questions?

This process can sprawl because you have to be concerned with consistency. Public sources of data also abound but only offer the granularity needed to be useful for directional reporting. An example is census data. There are extensive APIs to access this data, but the results may only be helpful in long-term planning exercises.

Data collection might also involve competitive intelligence. An example would be visiting other venues and monitoring prices or operational tactics. Competitive intelligence may also take the form of watching other industries that operate in similar spaces. For instance, what can we learn about loyalty programs from a company like Starbucks? You might discover that they aren’t appropriate for you.

We only touched on some high-level concepts here. Just understand that data collection will require combining I.T. skill sets, research knowledge, and critical thinking exercises. Getting your data in the right spot will take most of your time.

4.3 Modeling the data

Modeling the data is the fun part of working in analytics. We aren’t discussing modeling data in the database sense, although structuring the data is a process component. We also aren’t going into actually modeling the data here. Instead, we will speak about some of the tools you will need. You will leverage at least two languages (SQL and some other programming language) at the lower levels. Increasingly the modeling component of the data is becoming the most straightforward part as the tech giants seek to own this space. I don’t know if there are significant advantages to using one tool over the other. For instance, is there an advantage to using Google’s tools over Microsoft? Is there an advantage to using Python over R? The answers may vary. In some cases, yes, and in some cases, no. Over time, you’ll see the reliance on code wane.

Differences between R and Python may distinguish which tool you plan on using. This is especially true when we look to deploy results. R and Python are both highly extensible. There are libraries for almost everything, and the need to write your own implementations is likely minimal. If you have the need, using another language, such as C++, is better. However, C++ is significantly more complicated than many other languages. (Practically speaking, R is C since it is written in it)

Many analytics projects in Python will use the same relatively small sets of libraries. This is a nice feature because the code for one model will look exactly like the code for another. This will only sometimes be true in R, which is an advantage for Python users. Let’s look at an example.

The code to hierarchically cluster a data set in Python might look something like the following:

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Clustering algorithm applied in Python

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

from sklearn.cluster import AgglomerativeClustering

data = data.sample(n=1500)

cluster = AgglomerativeClustering(n_clusters=6,

affinity='euclidean', linkage='ward')

cl = py.DataFrame(cluster.fit_predict(data))Every other method in the module sklearn (Pedregosa et al. 2011) will resemble this example. This makes it easy and intuitive to run through several algorithms. For instance, as a demonstration, if you wanted to cluster with the Kmeans algorithm in Python, the code might look like this.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# kmeans algorithm applied in Python

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

from sklearn.cluster import KMeans

data = data.sample(n=1500)

cluster = KMeans(n_clusters=6, random_state=0)

cl = py.DataFrame(cluster.fit_predict(data))It is almost identical. Let’s compare this code to some R code that works with the same tool. The code to hierarchically cluster some data in R follows.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Hierarchical clustering algorithm applied in R

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

library(stats)

library(cluster)

data <- sample(data, 1500)

mod_data <- cluster::daisy(data)

cl <- stats::hclust(mod_data, method = "ward.D")

cuts <- cutree(cl, k = 6)

data$cluster <- cutsBoth languages begin by importing capabilities from libraries. The following code chunk uses the kmeans algorithm. It is housed in the stats library and works slightly differently than a hierarchical algorithm. R tends to feel more procedural than Python.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# kmeans algorithm applied in R

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

library(stats)

data <- sample(data, 1500)

cl <- stats::kmeans(data, centers = 6)

data$cluster <- cl$clusterThis code chunk looks similar, but that is only sometimes the case. R, like Python, has thousands of packages. However, in Python, there tends to be one correct way to do everything. It’s the Pythonic way. On the other hand, R is the wild west. Different algorithms often have authors who approach writing the code and dealing with objects differently. Luckily, several developers in R have attempted to solve this problem through wrapper packages that work as an API to the other libraries and add additional functionality.

You can even run Python from R using the reticulate (Ushey, Allaire, and Tang 2022) package. Packages such as caret (Kuhn 2022), mlr3 (Lang et al. 2022), and tidymodels (Kuhn and Wickham 2022) have attempted to create a standard API for many R functions. A similar approach can be taken regarding writing and understanding the code for many functions. The tradeoff is often speed. Despite this tradeoff, taking advantage of one of these frameworks is beneficial. They make it much easier to cover all steps of the modeling process. R and Python have learned from one another. Pick a tool and get good at it. I prefer R, but I admire Python. They both have their place, and it is easy to switch between them for data analysis.

The modeling process follows four discrete (often iterative) steps. We’ll refer to parts of this process in chapter 5.

- Evaluating your data

- Preparing your data

- Processing your data

- Validating your output

You’ll get better at this process as you gain experience, and it will become more intuitive. These projects tend to be repetitive, and you can encounter several problems with modeling your data. Every problem doesn’t always manifest, but some issues always arise. We’ll see how to solve some of those problems in the forthcoming chapters.

4.3.1 Evaluating your data

This refers to understanding what you are looking at. For example, how is the data structured, and what am I trying to do with it? You can occasionally do this with one of several built-in features in R. Other times, you’ll have to put on your thinking cap. Typical questions might include:

- What questions am I trying to answer with this data?

- Have we attempted to solve this problem before? What were the results?

- Are there deeply held beliefs as to what the solution might be?

- How is the data formatted?

- How sparse is this data?

- How current is the data? Does it matter if it is stale?

- What is this data’s provenance? Can I trust it?

- How much of it is missing, and why is it missing?

- Can I use this data?

- Do I need more data?

- Is the data categorical, ordinal, numerical, or mixed?

- Are we dealing with differences in units or scale?

- What do I plan to do if I don’t find anything, and how likely is this possibility?

Taking some time to get familiar with your data and its structure is critical to getting accurate results. Then, focus on the question at hand. An example is will current sales best predict future sales at all times during the year? What might work better? Frame your problem statement carefully.

Furthermore, if there are deeply held beliefs about the answer, you may have issues if your answer is antithetical to that belief. There are reasons why that belief is held. Most of the time the people have formed that belief are correct. Just use some extra discretion here if you determine another solution has merit.

4.3.2 Preparing your data

Preparing your data takes the most time. We’ll go into this process in some detail in chapter 5. If you have missing data, consider imputation. When dealing with mixed data sets, you must consider how to process it. Ordinal data might require you to approach the problem in a specific way. An example here might be the Holt-Winters 38 method for estimating time-series data. A particular method may also not be applicable because of the underlying structure within the data. When preparing your data, it is also critical to consider the two most common questions you will face.

- How will I deal with missing data?

- What methods do I plan on applying to this data?

Missingness is a huge problem. What do you do with NAs, NANs, inf? How sparse is OK? The answers here may vary. Additionally, if there is a systematic reason that the data is missing, your results may be invalid. Take a warning; dealing with missing data is frustrating work.

When you prepare your data, always ask if this is this something that will have to be repeated. I recommend prepping your data with code. For some reason, you always need to repeat projects. Documenting your ETL work is crucial. I start with SQL and push it to the point where it doesn’t make sense. I don’t duplicate information in SQL. For instance, I won’t dummy-code the data set in SQL. I will leave that for the analysis phase. This is more of a judgment call. You have to think about where you can do this the most efficiently. Specific methods such as Latent Class Regression only accept discrete data, and how you transform numerical data into discrete data can impact your results.

4.3.2.1 Selecting the appropriate technique for analyzing your data

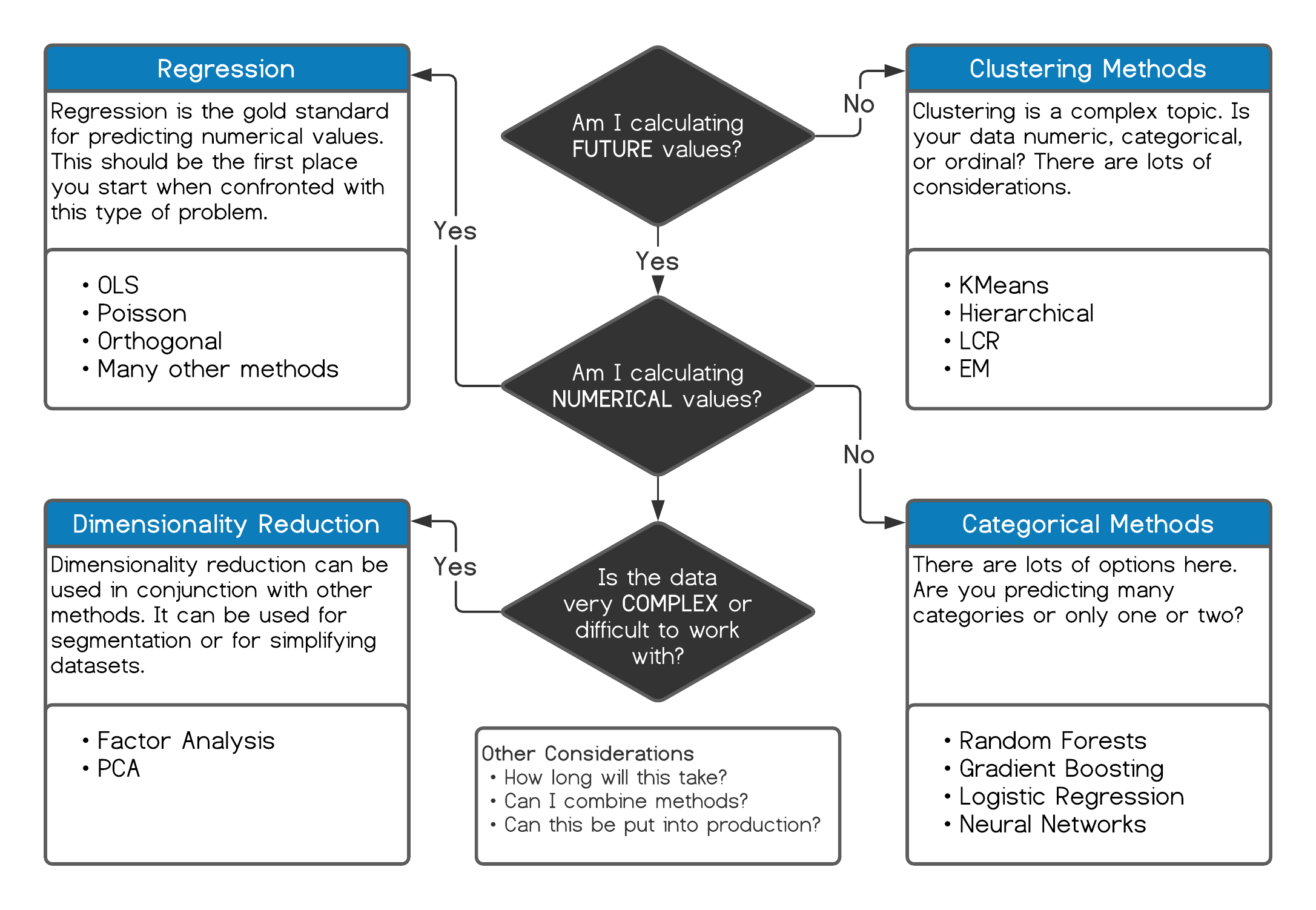

Gone are the days of an expert having to use sound judgment to select the appropriate method for processing data. Hardware and software advances have removed a resource constraint that has delayed the analytics revolution that began in the early 2000s. The future is now. In the past, a researcher may have had to purchase time on a main-frame39 (you may not even know what that term means) and therefore needed to have a good idea of what technique they would want to leverage to solve the problem. Analysts in these modern times can afford to be lazy. Modern analysts only have a few considerations regarding how they approach a problem. See figure 4.4.

Figure 4.4: Choosing the right technique

I am exaggerating a little here. Many of these techniques require high rigor to validate the results. However, you have it much easier than analysts from twenty years ago. The surplus of methods has become a problem in and of itself. Additionally, it is easy to get into a rut. For instance, I like deep learning so I will use it for every problem I face. If all I want to use is a hammer, I will use it to fix everything. It’s a variation of something we have already discussed, and it might warrant being repeated. Sometimes a wrench will make your life easier even if the hammer will work.

4.3.3 Processing your data

Begin by looking for the simplest solution first. Stingy, parsimonious models tend to be the most forgiving and friendly. Always look for the simplest solution. This is especially important for interpretability but also for durability. More straightforward solutions are more elegant and easier to deal with. Always approach processing in an intelligent, procedural way. Let’s illustrate this with a brief example:

“The ticket sales manager wants to understand who are the most likely candidates in our system to purchase season tickets. They also want to understand who is most likely to spend more or to upgrade their seats.”

How could you approach this problem once you have gathered the cleaned data? This is a classification problem related to lead scoring. While OLS regression tends to be the best place to start and the gold standard for estimating numerical values, Logistic regression tends to be the best place to begin when trying to estimate classes. There are even particular forms, such as “multinominal logistic regression” (Ripley 2022), that can estimate several classes, not just binary classes.

Over time you’ll learn that specific techniques work better for particular problems. Techniques may also provide almost identical results. For example, I’ve found that random forests and gradient boosting deliver similar results. While less interpretable, they don’t require as much rigor as regression. Regression forces you to consider many issues, such as Heteroskedacity, Multicolinearity, and Autocorrelation. I always like to use multiple techniques and then compare the results. Getting more support for a conclusion is always a good thing. Unless you are dealing with vast amounts of data, there will be little penalty for taking this route. These tools make it easy.

Keep in mind how results are deployed. Regression is represented by a mathematical formula. That means that results can be computed almost instantly, and the model won’t change. Deep learning algorithms can be adaptive and produce unexpected results if not monitored. Many examples of chat-bots developing racist 40 behaviors. Stick to the most straightforward solution unless you need higher degrees of precision or deployment requires a specific approach. Don’t fall into the rut of “I have a problem; let’s bludgeon it with Deep Learning.”

4.4 Evaluating your results

Evaluating results can be the best or the worst part of a project. Did you discover a solution? Regardless of whether you solved your problem, this stage of the process will give you some great information. If you don’t find a solution may tell you there isn’t a solution in the data. It may also indicate that the problem is more nuanced and needs more sophisticated thought. Let’s examine an example.

A marketing manager wants to understand if outreach efforts impact season ticket retention.

You collect data from the CRM system, such as the number of calls and emails, attendance regarding non-sport events, etc. You use this data to attempt to estimate the probability that season ticket holders will or will not renew their tickets. Unfortunately, outreach appears irrelevant (results are insignificant to the model). You also discover that ticket usage and tenure are the only variables that appear significant (ignoring macro factors such as the economy and team performance). Does this mean that we shouldn’t call or email clients? Of course not, but it does mean we may need to examine how we incentive our client representatives more closely. We also need to be careful about communicating this type of result. We’ll discuss this in the next section.

There is also a technical component to evaluation. Different models can be compared against one another with an ANOVA 41 or the BIC 42, or the AIC 43. For example, you could estimate the efficacy of a call campaign with a lift chart represented by a ROC 44 curve. OLS regression uses an F statistic, P-values, and R-squared values. Results can be cross-validated and compared to a control group or holdout sample. Logistic regression models will be concerned with Accuracy, precision, sensitivity, specificity, and overdispersion. Many other diagnostic features must be evaluated to ensure your model does what you want. Ultimately, you’ll always want to compare results to a control group and make iterative improvements. A/B testing is often the best way to accomplish this goal once something is put into production.

Evaluating your results is an exercise that requires some technical rigor and domain knowledge. You don’t have to find a solution but should always learn something. Think carefully about how you approach this component of modeling your data. This is the second most time-consuming component of the project, and it has the most significant influence on whether the project will succeed or fail.

4.5 Communicating the results

Getting your research into the hands of Executives or Managers that need to understand the problem and potential solution is more complicated than it sounds. Communicating the results of a project that may require more esoteric techniques is an art. Every large management consulting firm has frameworks around problem-solving and framing the results. You can often borrow from these folks. Remember that results can be complex or involve difficult concepts, and it isn’t always easy to ELI5 45. As your credibility grows or an organization matures, this process becomes more manageable. Exorcising that bias may be impossible if your colleagues suffer from confirmation bias. This is incredibly important to understand.

“We often use reasoning not to find truth but to invent arguments to support our deep and intuitive beliefs.”

— Johnathan Haidt, “The Happiness Hypothesis”

This quote from Haidt (Haidt 2006) hammers home the concept of confirmation bias. The results, in this case, may or may not be about winning an argument. This can be a frustrating phenomenon. On the other hand, it also has some merit. How much experience do you have with this problem? Are there strong beliefs as to the solution? Understanding how and why someone might interpret a solution (especially if that solution challenges preconceived notions) must be considered. If a solution could threaten someone, consider how you present it. Even think about the words you use and how the recipients of your message perceive them. Could someone perceive your results as threatening or insulting? What happens if I am gas-lighted? Always take a step back and examine if your analysis is fair. Would it have made a difference to do this another way? If something doesn’t matter, don’t worry about communicating it.

Additionally, there are best practices that you can follow. For example, the higher someone’s title is, the more words and bullet points to include. The lower the title or the more technical the audience is, the more graphs and explanations I include:

- Executives: Bullet points that refer to the solution. Keep it terse. Get to the point.

- Managers: Include more specific explanations about their domain knowledge.

Resist the urge to demonstrate your domain knowledge. Typically, nobody cares how you did something. They don’t care about Support Vectors, Eigenvalues, or Deep Learning. Instead, they care about the results and, in some cases, how you got there (especially if it contradicts their beliefs). Instead, take a collaborative approach to demonstrate findings and ask questions. You’ll gain more credibility over the long term and have better success implementing your solutions.

R also provides some great features for helping you communicate results and findings. R Markdown (Allaire et al. 2020) makes creating publishable documents that include code, graphics, and mathematical formulas easy. This book was written using it. We discussed Shiny (Chang et al. 2022) earlier. These tools make R an excellent choice for building documents and dynamic web pages.

4.6 Deploying the results

Deployment could mean different things. One refers to people, and one relates to systems.

- Communicating the results (The subject of the last section)

- Operationalizing the output (The automation component discussed in figure 1.1.

The second part of deploying results refers to automating a process and putting those solutions into production. Multiple tools make this possible. Although this is where other languages have an advantage over R. Compiled languages such as C++ can be much faster than R and are more full-featured in some sense, there are some exceptions. SQL Server has supported an integration with R 46 and Python since 2016, although it isn’t clear how widespread its use has become. Google, Amazon, and Microsoft are all building analytics frameworks into their cloud-based DBMSs. They allow you to turn up the computing power to make your models run much more quickly, assuming you can take advantage of a technique such as multi-threading (Which R does not natively support). Thinking about how to make something more efficient has probably already been done for you. At this stage, R may be used for prototyping and something else for the actual deployment.

Where is this valuable?

- Forecasts on ticket sales could be made daily or by the minute that update a report.

- Customer lead scores could be dynamically updated throughout the year based on certain conditions.

- A marketing campaign’s predicted vs. actual vs. expected results could be constantly evaluated for ROI.

- Ticket Prices could be automatically updated on a tight interval to optimize sales or revenue.

There are many applications. Additionally, you could always write a wrapper (in windows) within your system that runs a script using a simple batch script (A notepad file saved as .bat). The following example runs an R script called YourRScript.R.

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# Batch script for automation

#-----------------------------------------------------------------

# REM This command will call an R Script from a program or

# scheduling tool

# "C:\Program Files\R\R-Version\bin\x64\R.exe" CMD BATCH

# --vanilla --slave ""C:\locationOfScript\YourRScript.R"You can write a similar bash script on a Linux box. However, if you are dealing with more complicated systems, you may need developers to automate your process. Again, your context and available skill sets will tell you what direction to take.

4.7 Key concepts and chapter summary

How you structure a problem is a critical component of the project management process. This becomes more important as projects grow in complexity and require more significant numbers of people to be managed. Any project can benefit from a systematic approach consisting of a few steps. I typically break these steps into six components:

- Defining a measurable goal or hypothesis

- Data collection and management

- Modeling the data

- Evaluating your results

- Communicating the results

- Deploying the results

You’ll work through these steps whether you mean to or not. They are the natural order that these projects take.

- Defining a goal tends to be the most challenging part of an analytics project. It is also the most important. Even if you aren’t putting together a formal hypothesis test, you must still be concerned with scope creep. Please spend some time on this step and get it right.

- Data collection and management is typically the most time-consuming component of one of these projects. Getting quality data can take time and effort. If you have to collect the data yourself, be systematic about it. Document what you are doing for reproducibility.

- Modeling the data is the fun part of an analytics project. You have lots of options but start with the simplest method first. While deep learning has been more prominent recently, it isn’t always the best tool. Interpretability can be important here. Put some thought into why you are using one technique over another.

- Evaluating the results is a quantitative and qualitative exercise. It is never just about the data. Think about your output in the context of the exercise and give it a good smell test. Are the results logical? Can you take action on them? Are they relevant to your goal?

- “Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication.” This quote is attributed to Leonardo Da Vinci. Only God knows where it came from. Keep it in mind. Use bullet points. Keep your results simple to understand.

- Deploying results can mean multiple things. There are lots of tools available to put your results into action.